Why Large Product Teams Create Fragmented Experiences

Rethinking the Product Operating Model: From Siloed Journeys to Cohesive Platforms

Most product organizations today are doing exactly what they were taught to do: autonomous teams, empowered decision-making, clear ownership, continuous discovery, outcome-oriented goals. And yet, the user experience often feels increasingly fragmented. The navigation shifts between areas. Concepts are named differently. Similar problems are solved multiple times. Each part works, but the whole does not. This is not a talent problem. It is not a maturity problem. It is a structural problem.

The uncomfortable truth about modern product teams

Product organizations have spent the last decade refining how to empower teams. We’ve invested in cross-functional squads, autonomy, continuous discovery, outcome-based goals, and modern product practices. The intent is clear: move faster, stay close to users, and avoid centralized bottlenecks.

And yet, many products feel increasingly fragmented.

Users encounter inconsistent terminology across features. Workflows feel stitched together rather than cohesive. Similar problems are solved in different ways depending on which team touched them. Internally, teams ship valuable improvements, but the overall product becomes harder to reason about, harder to scale, and harder to evolve.

This is the paradox: we optimized for autonomy, but underinvested in the structures that make autonomy converge rather than diverge.

The issue is not empowered teams. The issue is empowering teams without designing the system they operate inside.

This is not a critique of individuals, competence, or intent. It is a critique of the product operating model itself. And it affects startups, scaleups, and enterprises alike — just at different speeds and levels of visibility.

To address it, we need to move beyond fixing symptoms and start redesigning the system.

Fragmentation is a system problem, not a people problem

When product leaders observe fragmentation, the instinct is often to search for execution gaps:

- “Teams aren’t collaborating enough.”

- “We need better alignment rituals.”

- “We should improve documentation.”

- “We need stronger governance.”

These responses assume the problem lives in behavior. But fragmentation often emerges even when teams are highly capable, motivated, and user-focused.

Consider what typically happens in well-intentioned product organizations:

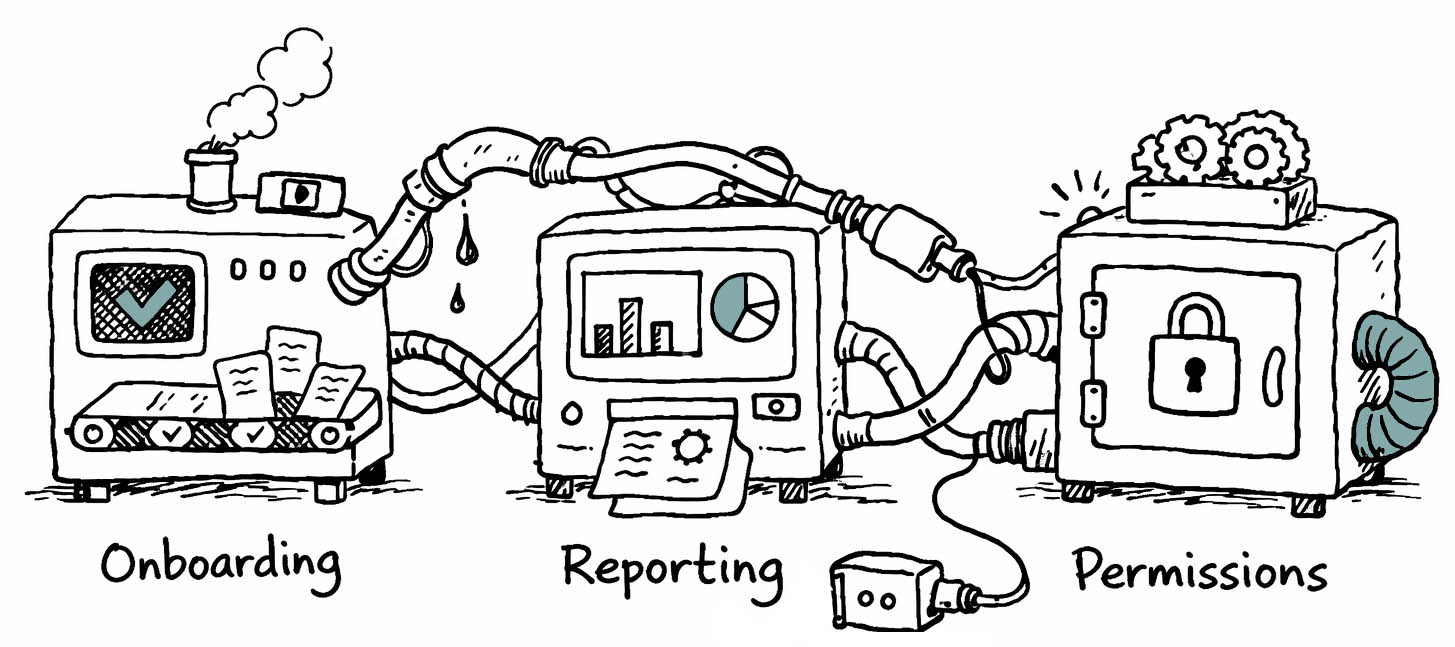

- One team improves onboarding.

- Another improves reporting.

- A third optimizes permissions.

Each runs good discovery. Each ships useful changes. Each hits its outcomes.

Over time, each team introduces small, local decisions: a naming choice here, a workflow tweak there, a different mental model for similar concepts. None of these decisions are irrational. In fact, they are often optimal within the team’s context.

The issue is not that teams make bad decisions. The issue is that local optimization accumulates into global incoherence.

This is predictable behavior given the structure we’ve designed. When teams are accountable primarily for their slice of the experience, they will rationally optimize for that slice. When success is measured locally, local coherence is what emerges, not system coherence.

This is what structural fragmentation looks like: the organization is functioning as designed, but the design itself produces unintended outcomes.

If we accept that, the question shifts from “How do we get teams to behave better?” to “What kind of system would naturally produce coherence instead of fragmentation?”

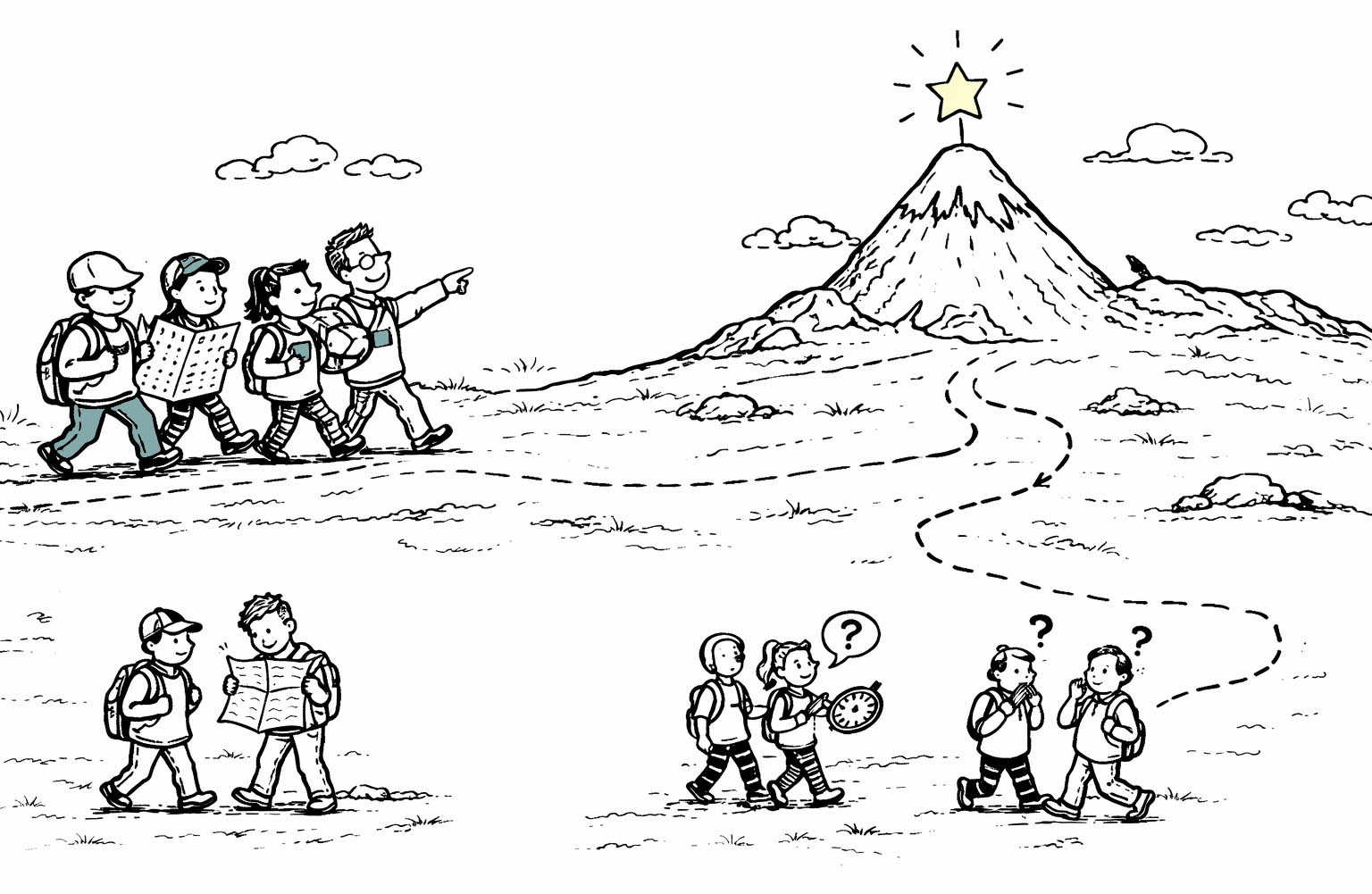

Why autonomy without shared framing leads to divergence

Autonomy is neither good nor bad by default. It amplifies whatever context surrounds it.

Autonomy with strong shared framing produces alignment. Autonomy without shared framing produces divergence. Control without autonomy produces stagnation.

Many organizations believe they have strong framing because they have a vision statement, a strategy deck, and quarterly OKRs. But these artifacts often communicate direction at a surface level while leaving deeper understanding fragmented.

Teams align on metrics, but not on meaning. They share goals, but not mental models. They know what they are responsible for, but not how their decisions shape the whole.

This is why autonomy drifts toward divergence. Teams are empowered to decide, but lack the shared context needed to make decisions that converge.

This is not a failure of empowerment. It is a failure of system design.

The answer is not less autonomy. It is stronger structures that make autonomy converge.

That starts with shared intent.

Shared intent and context must be stronger than local goals

Most product organizations already align teams around outcomes. They use OKRs. They define success metrics. They articulate goals.

But alignment on metrics is not the same as alignment on understanding.

Two teams can share the same objective, for example, “Improve retention”, and still develop completely different interpretations of who the user is, what the core problem is, and what kind of product they are building.

Shared intent requires more than shared targets. It requires:

- A common understanding of the user and their context

- A shared narrative about what the product is and is not

- A collective sense of long-term direction

- Agreement on the core problems worth solving

This is not process overhead. It is infrastructure.

Without it, teams operate with partial maps. They make good local decisions guided by different internal models. The organization becomes a collection of parallel truths rather than a shared reality.

Strong shared intent doesn’t reduce autonomy, but helps autonomy converge. Without it, every empowered decision increases divergence.

Team boundaries silently shape the user experience

Once shared intent is established as foundational, the next structural force becomes visible: team boundaries.

Every team boundary becomes a seam in the user experience — whether we intend it or not.

We rarely design team boundaries with this in mind. We design them around ownership, throughput, reporting lines, or perceived efficiency. But users do not experience org charts. They experience seams.

Org charts encourage boundary thinking. Backlogs encourage local optimization. Roadmaps reinforce commitment to planned slices of work.

Together, these structures subtly teach teams to focus on “their part” of the product. Teams optimize what they own. Users experience the sum of those optimizations.

This is why fragmentation emerges even when collaboration is strong. The structure itself creates separation.

If org design shapes product design, then team boundaries are not just operational decisions. They are product design decisions.

Which leads to one of the most common structural mistakes: organizing teams around journeys instead of capabilities.

Why journey thinking breaks platforms

Journey maps are useful tools. They help teams understand context, friction, and emotional flow. The problem begins when journeys become ownership structures.

When teams are assigned to journeys — onboarding, activation, upgrade, reporting — they optimize for sequences. They design flows, refine steps, and improve transitions.

Over time, predictable patterns emerge:

- Similar capabilities rebuilt in multiple places

- Inconsistent patterns across flows

- Shared concepts evolving differently by journey

- Increasing brittleness as new use cases appear

Journeys optimize paths. Platforms require capabilities.

Instead of mapping only flows, organizations need to map the underlying capabilities their product depends on: identity, permissions, collaboration, data models, insights, workflows, configuration, communication.

These are not technical abstractions. They are product primitives.

Assigning teams to capabilities rather than journeys changes what gets optimized:

- Teams build reusable foundations

- UI patterns become more consistent

- New journeys become easier to support

- The product evolves as a system rather than stitched flows

This doesn’t remove the need to care about journeys. It changes the unit of optimization. Instead of improving isolated paths, teams strengthen the platform beneath them.

The benefit is not just architectural. It is experiential. Users encounter fewer seams because the product is built from shared primitives rather than parallel flows.

This shift also exposes another issue: discovery itself is often structurally siloed.

AI products make “platform over path” thinking non-optional

AI-based products expose a structural weakness in many product organizations: path-based design collapses almost immediately.

In traditional software, you can sometimes get away with linear flows and journey-based ownership. With AI, that illusion breaks fast. Inputs vary. Outputs vary. Behavior shifts as models change. What you are shipping is no longer a predictable flow, but a behavioral system that must hold up across messy, real-world use.

This forces a different design stance. You are no longer optimizing paths. You are designing a platform that governs behavior.

If AI capabilities are treated as local team responsibilities, fragmentation accelerates. Different teams implement different guardrails, assumptions, and definitions of quality. If AI is treated as a shared platform concern — with explicit ownership, shared signals, and common behavioral standards — the system can evolve without losing coherence.

AI doesn’t introduce a new problem. It removes the safety net. It makes visible what was already true: teams optimizing paths fragment the product. Teams contributing to shared capabilities compound coherence.

Which brings us to the next constraint: if behavior must be continuously calibrated, discovery and learning can no longer live inside individual teams.

Why discovery must flow across teams (or fragmentation becomes inevitable)

Continuous discovery is widely accepted as best practice. Teams talk to users, test ideas, and validate assumptions.

But discovery is usually scoped to the team.

Each team builds its own understanding of users. Each frames problems differently. Each collects insights in isolation.

Over time, the organization accumulates multiple incompatible versions of the user. Teams use different language for the same needs, prioritize different problems, and form different narratives about what matters.

This isn’t because teams are doing discovery wrong. It’s because discovery is treated as a team activity rather than shared infrastructure.

If discovery doesn’t flow across teams, fragmentation is inevitable.

Shared learning loops matter more than shared ceremonies. Cross-team synthesis matters more than local velocity. User understanding must be treated as a shared asset, not a team artifact.

This doesn’t require more rituals. It requires designing discovery as a system: shared insight repositories, shared user narratives, shared problem framing, and regular synthesis across the organization.

Without this, even capability-oriented teams will drift apart in how they interpret what they are building for.

The startup operating model enterprises should study more closely

Interestingly, many early-stage startups do not struggle with this level of fragmentation. Not because they are more mature, but because their operating model naturally enforces coherence.

Small product organizations typically have:

- Few teams

- High shared context

- Constant informal communication

- Close proximity to users

- Weak boundaries between ownership areas

The advantage is not speed. It’s coherence.

Everyone knows roughly what others are doing. User feedback spreads quickly. Decisions are made with awareness of the broader system because the system is visible.

As organizations scale, this coherence erodes. Teams specialize. Boundaries harden. Context fragments. Coordination mechanisms are added to compensate, but they often treat symptoms rather than causes.

The goal isn’t to make large organizations operate like startups. It’s to preserve startup-level coherence while scaling.

That requires rethinking the product operating model itself.

Toward a better product operating model

If fragmentation is a predictable outcome of system design, coherence must also be designed.

A healthier product operating model doesn’t rely on more process. It rests on stronger structural assumptions.

Several characteristics emerge:

Teams are accountable not only for outcomes, but for their contribution to the platform. Success is measured not just by local impact, but by whether the system becomes more coherent over time.

Shared capabilities have explicit ownership. Not as a separate coordination layer, but as a core product concern more teams can work on. One that evolves assets rather than incidental infrastructure.

A strong product narrative replaces heavy coordination rituals. Instead of more alignment meetings, organizations invest in clarity: what the product is, who it serves, what problems matter, and how the parts connect.

Discovery becomes shared infrastructure. Insights flow across teams. Understanding accumulates. Learning compounds rather than resetting at team boundaries.

Org design is treated as product design. Team boundaries and ownership models are shaped with user experience in mind, not just delivery efficiency.

This is not a framework or a process. It is a shift in what we treat as first-class design.

Stop fixing symptoms, start designing the system

Fragmentation is not a mystery. It is not a cultural flaw. It is not a failure of empowerment. It is the natural outcome of how most product organizations are designed.

When we respond with more rituals, more coordination layers, and more alignment ceremonies, we treat symptoms. The underlying structure stays the same, so the outcomes persist.

The deeper opportunity is not tighter control. It is designing the system so autonomy naturally produces coherence.

If we want cohesive products, we must design cohesive product organizations.

That means designing for shared intent. Designing team boundaries intentionally. Designing discovery as shared infrastructure. Designing capabilities and platforms instead of optimizing isolated paths. Designing the operating model with the same care we apply to the product itself.

Because in the end, the organization is part of the product.

- Product Roadmaps Relaunched by C. Todd Lombardo, Bruce McCarthy, Evan Ryan, Michael Connors

- Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton, Manuel Pais

- Empowered by Marty Cagan

- The Art of Action by Stephen Bungay

- Continuous Discovery Habits by Teresa Torres

- Deploying Product Vision and Strategy at Lenus eHealth by Magnus Christensson

- Designing AI Systems That Actually Work (Video) by Various speakers

- On Generative Features by Stephen Anderson

- From Paths to Sandboxes conference talk [video] by Stephen Anderson