Experimenting companies outperform the base

How experimentation powers business growth

Validate before you build with the Validation Patterns printed card deck

A collection of high-impact experiments to ensure you're on the right path before investing time and money.

Get your deck!You know the stakes are high when it comes to launching new features or products.

Whether it’s a brand-new product line or just a small update, there’s always that nagging uncertainty: Will users actually want this? Will this feature move the needle? Relying on intuition or past experiences can lead to costly mistakes—launching something that users don’t find useful, or missing an opportunity to innovate effectively.

But there’s a way to reduce this uncertainty.

There’s a way to test your ideas before committing resources to full-scale development.

The key is business experiments. By running small, structured tests, you can validate your ideas early on, get actionable insights, and avoid wasting resources. But the key question is: how do you ensure you’re running the right experiments, at the right time, and making sure they are actionable and lean?

Experimentation is not just a tool—it’s the key to unlocking innovation

- Stefan Thomke

Business experimentation: Not just a validation tool, but a strategy for growth

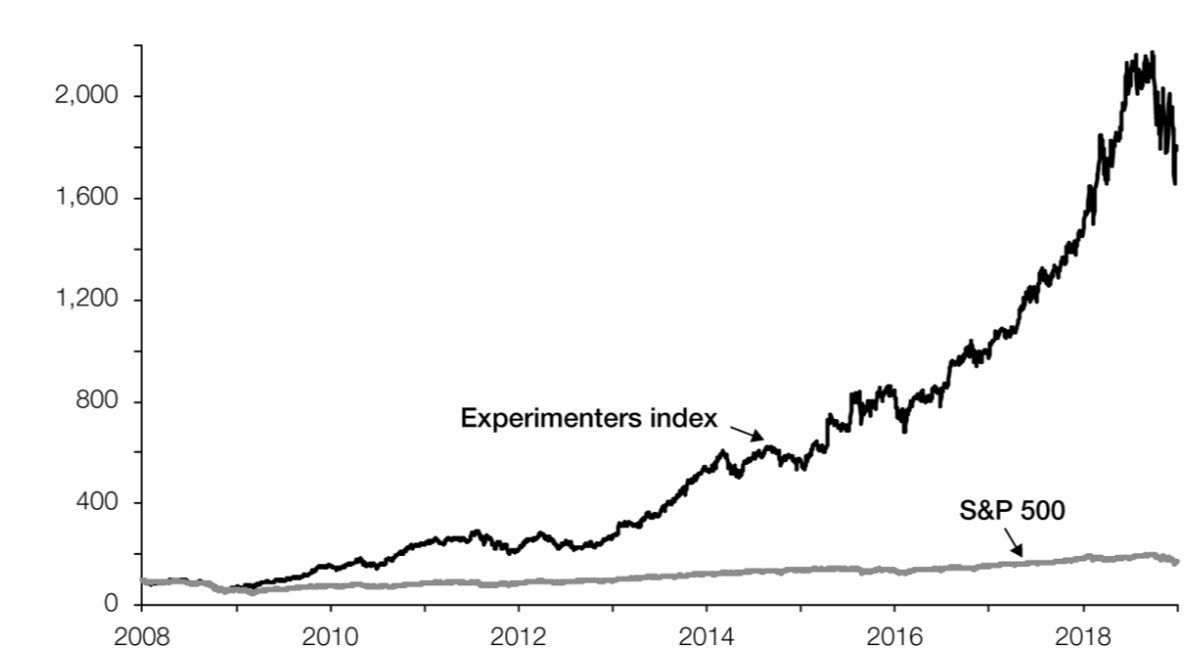

Experimentation isn’t just a tool – it is what drives innovation. Researchers at Harvard Business School, led by Professor Stefan Thomke, have explored the impact of experimentation on business performance. They created the Experimenters Index—a collection of leading companies that actively invest in experimentation—and compared it to the performance of the S&P 500.

Here’s what they found:

Companies that invest in experimentation grow a lot faster than those that do not.

Take a look at the graph below:

The Experimenters Index has significantly outperformed the S&P 500 over the past decade. The clear takeaway? Companies that systematically test ideas and make decisions based on real data are able to gather better insights, make better decisions, and ultimately, grow faster.

While correlation doesn’t always equal causation, the message is clear: experimentation enables growth. Lots of small, informed decisions add up over time and create lasting success across various areas of your business.

How to start experimenting smarter

When done right, experimentation can transform your product strategy. But how do you ensure that your experiments are effective and provide real insights? Let’s break down a few steps, bolstered by key insights from Experimentation Works, to help you get started:

-

Start small, Fail fast. Before committing to full-scale development, run quick, low-cost experiments to gather initial data. Use A/B testing, prototypes, or mockups to validate your core assumptions. As Thomke emphasizes, the goal here is to fail fast and learn quickly, minimizing costs and moving forward with more confidence.

-

Let data guide your decisions. Your experiments should generate actionable data, not just opinions. Use metrics like user engagement, conversion rates, or feedback to inform your decisions. Avoid guessing—let the data tell you whether to pivot, persevere, or scrap an idea. This aligns with the principle that “data trumps opinion,” and testing should be used to settle debates with evidence.

-

Iterate with purpose. Testing is not a one-time process. Each experiment should build upon the previous one, refining your product step-by-step. Focus on one key hypothesis at a time and iterate until you have enough data to make a confident decision. This echoes the idea that you should practice “high-velocity learning” through quick iterations.

-

Learn from failures. Not all experiments will yield the results you expect, and that’s okay. Thomke emphasizes that failed experiments provide just as much value as successful ones because they highlight what doesn’t work. Use those insights to adjust your approach and get closer to a winning solution.

-

Foster a culture of experimentation. Thomke makes it clear that experimentation should be embedded into the DNA of an organization. Leadership needs to support this culture by empowering all employees to propose and run experiments. This not only accelerates the innovation process but also creates a repository of insights for future initiatives.

One of the most challenging aspects of experimentation is knowing which experiments to run first. With so many potential ideas and variables, how do you decide which ones will deliver the most valuable insights?

This is where the Validation Patterns card deck can help. It’s a toolkit designed specifically to help you run smarter, more effective experiments. Each card contains a proven, lean experiment that you can apply to quickly test and validate different aspects of your product strategy.

With the card deck, you no longer have to guess which experiments to run. The deck gives you pre-designed experiments to test product-market fit, usability, customer interest, and more—helping you gain insights faster and with less risk. This approach streamlines the experimentation process and ensures that every test you run is aligned with your goals.

How could a product experiment look like?

Let’s take a quick example. One product team was considering adding a new feature to their app. Before building the feature, they used the landing page smoke test (Spoof Landing Pages) from the card deck to gauge interest. They created a simple landing page describing the feature and tracked user sign-ups and interest.

The results? Data showed that user interest was much lower than for the baseline of other features. By running this low-cost experiment, the team saved months of development time and thousands of dollars, allowing them to pivot and focus on more impactful features.

Stop wasting time on features that might not work. Start testing smarter, make informed decisions, and grow faster—just like the companies in the Experimenters Index. Embedding experimentation into the core of your strategy will not only validate your product ideas but will also position you for long-term success. As Thomke points out, experimentation is not just a tool—it’s the key to unlocking innovation.

- Thomke, S. (2020). Experimentation works: The surprising power of business experiments. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Thomke, S., & Beyersdorfer, D. (2021). Tesla: The $5 billion question. Harvard Business School Case 621-088.