Stop Designing Paths. Start Designing Platforms

How platform thinking can unlock user mastery and sustained value

Turn insights into action with the Persuasive Patterns card deck

Master the science behind user motivation and create products that drive behavior.

Get your deck!Imagine a user who has been with your product for months.

They know where everything is. They’ve learned the quirks. They’ve built habits. They’re no longer asking, “What do I do next?” They’re asking, “What else can I do with this?”

And then they hit your “perfect” flow (hint: it’s not).

A rigid sequence. A modal they can’t dismiss. A forced step that assumes one goal, one order, one outcome. The experience that helped them when they were new now feels like it’s slowing them down.

That’s often the moment engagement starts to fade—not because the product is missing features, but because the product is still designed like a conversion machine.

When users outgrow your paths, you need to give them a platform.

Paths are great. Until they aren’t.

Path-based design is built around predictability.

You define the steps, the order, and the “success” state. That structure is useful when users are learning, when tasks are complex, or when mistakes are costly. Paths reduce uncertainty. They make a product feel approachable.

But paths also have a ceiling.

As users gain skill, the same structure that once helped them becomes a constraint. It narrows possibilities. It turns exploration into compliance. It can quietly shift your product from “helpful” to “controlling.”

This is why so many products do well at activation and still struggle with long-term engagement.

They keep optimizing the path long after the user needs it.

A platform is a different promise

A platform isn’t “anything goes.” It’s not the absence of design.

A platform is what you get when you stop designing for a single outcome and start designing for a range of outcomes—many of which you didn’t plan.

Platforms are built around capabilities, not instructions. They let users combine, interpret, and adapt your product to their own context. They don’t remove structure, they change what structure is for.

Instead of “follow this journey,” the promise becomes:

“Here’s what you can do. Make it yours.”

Stephen Anderson describes this shift as moving away from tightly guided journeys and toward more generative systems, where the product’s value grows through what users are able to create, explore, and discover over time.

The signs your product needs more platform

You don’t need to rebuild everything to benefit from this shift. You just need to notice where paths are starting to work against you.

A product often needs more platform when:

- Experienced users keep looking for shortcuts and workarounds

- Support questions shift from “how do I start?” to “can I do X instead?”

- Engagement becomes repetitive rather than expanding

- Users succeed once, then plateau

- Features feel “done” rather than “usable in new ways”

When you see these patterns, it’s usually not a persuasion problem.

It’s an autonomy problem.

Why platforms support mastery

Mastery doesn’t come from following steps. It comes from practice, experimentation, and self-directed goals.

When users can choose direction, they start to invest differently. They test ideas. They learn the boundaries. They develop personal workflows. They begin to feel ownership—not because you told them what to do, but because the system allowed them to decide what “good” looks like.

This is the core difference:

Paths optimize for completion. Platforms optimize for growth.

That growth is one of the cleanest sources of long-term engagement you can design for.

To make this distinction more tangible, it helps to look at systems that already behave like platforms across very different domains.

Examples of platforms (and why they matter)

To make the idea of “designing platforms instead of paths” more concrete, it helps to look at systems that are clearly not built around a single intended journey. These examples are intentionally diverse, yet they all share the same underlying logic: they expose capabilities, not instructions.

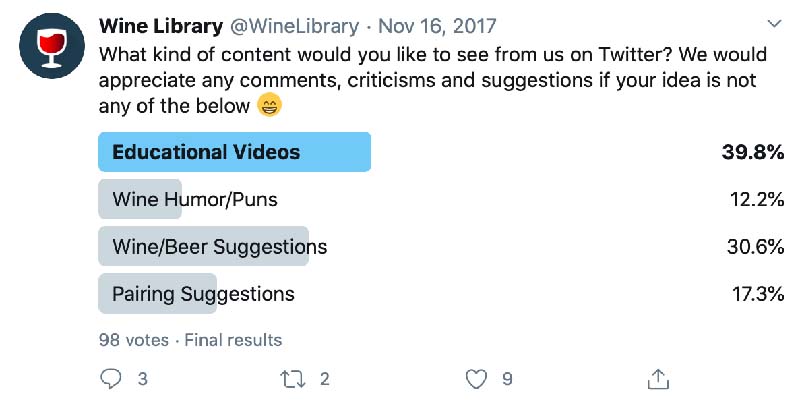

Twitter is not designed around a defined user path. There is no correct sequence of steps that guarantees value. Instead, it provides a small set of primitives — posting, replying, following, liking, reposting, and leaves it to users to combine them. Some people use Twitter as a news feed, others as a publishing tool, a customer-support channel, or a social graph. The platform does not decide which outcome is correct; it simply enables interaction at scale. This is a clear example of a platform where value emerges from participation, not completion.

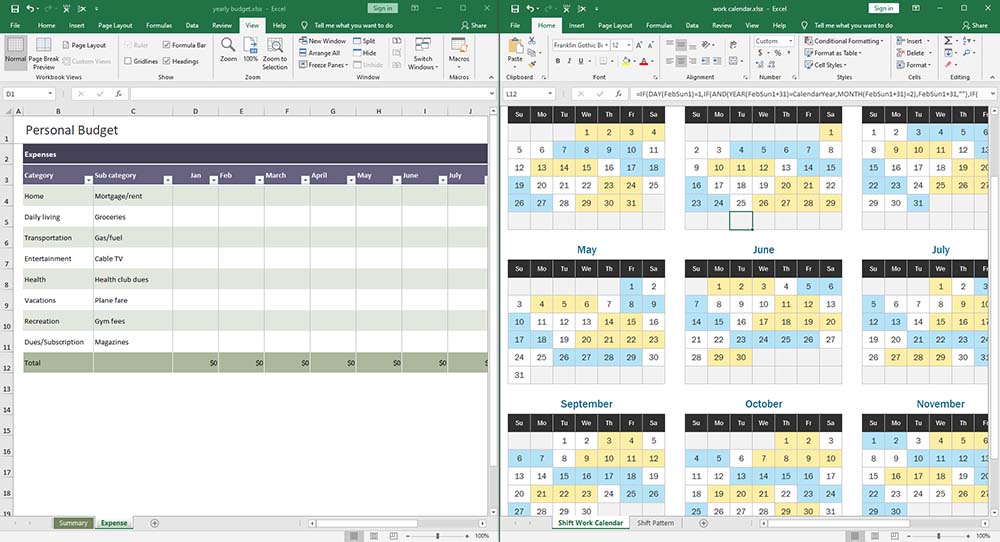

Microsoft Excel

Excel is rarely described as a platform, yet it fits the definition precisely. It does not prescribe what users should build. Instead, it offers a flexible set of components — cells, formulas, charts, macros, and connectors — that can be combined in countless ways. Excel is used for budgeting, forecasting, dashboards, lightweight databases, and even application-like tools. There is no single “flow” to follow. The power of Excel comes from its openness and composability, not from guiding users through predefined steps.

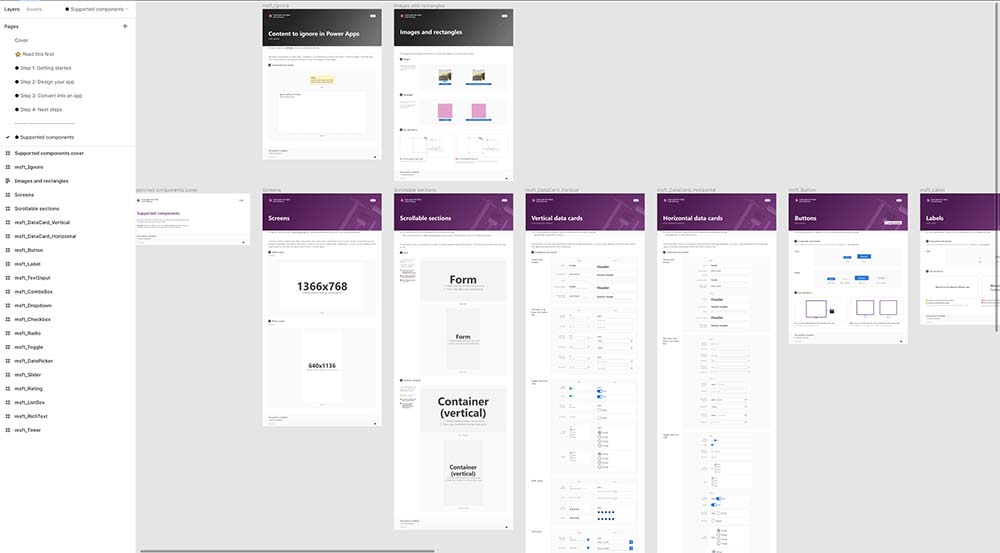

Figma

Figma is a design environment rather than a process. It does not force designers through a linear workflow from idea to output. Instead, it provides shared canvases, components, libraries, and plugins that teams can adapt to their own ways of working. Some teams use Figma primarily for UI design, others for workshops, documentation, or early exploration. The platform supports collaboration and extension, but avoids encoding a single “right” design path.

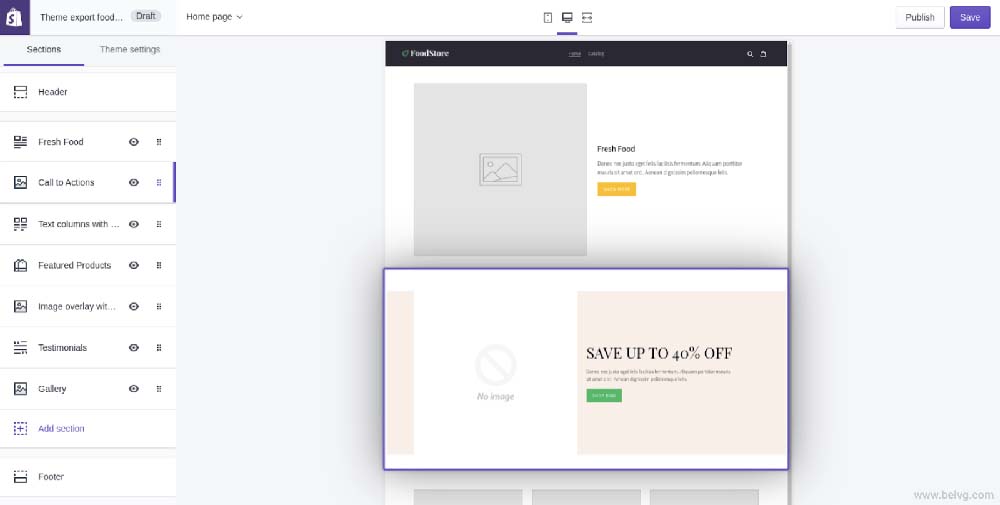

Shopify

Shopify illustrates platforms in a commercial context. It does not define how a business should operate; it provides building blocks such as product catalogs, payments, themes, and integrations. Merchants decide what kind of store they want to run, which channels they use, and how their workflows are structured. Through apps and extensions, the platform can be reshaped without changing its core. This makes Shopify less like a guided setup wizard and more like an ecosystem that supports many business models.

So what do you actually design?

The move from paths to platforms isn’t philosophical. It shows up in mechanics.

A platform typically increases engagement by doing more of the following:

1) Replace forced sequences with optional entry points

Instead of “Step 1 → Step 2 → Step 3,” give users multiple starting points that all lead to value. New users can still take the guided route. Returning users can jump in where it makes sense.

2) Expose capabilities earlier, without requiring completion

Many products hide power behind completion. Platforms do the opposite: they let users see what’s possible and opt into it when ready.

3) Design for combinations, not single features

Platforms become valuable when features can be combined. The experience isn’t “use feature A,” but “use A + B to solve your situation.”

4) Make exploration safe and reversible

If you want exploration, reduce the perceived risk. Clear undo, previews, drafts, sandboxes (as a concept), and reversible decisions matter more than people think.

5) Measure more than completion

Platforms produce outcomes that are harder to predict. If your metrics only track funnel completion, you’ll keep designing funnels. You’ll need instrumentation that also captures expansion: depth of use, reuse, composition, and self-directed goal achievement.

The discipline is knowing where paths still belong

Paths don’t disappear. They just become scaffolding.

Paths are still useful when:

- the user is new

- there’s a critical setup step

- errors are expensive

- the product must teach a concept

The mistake is treating every experience as if the user is always a beginner.

Mature engagement design often looks like this:

Paths help people start. Platforms help people stay.

A simple exercise to begin the shift

Pick one flow in your product that you’ve optimized heavily.

Now ask two questions:

- What is the user trying to achieve here—beyond completing the flow?

- What would it look like if this flow was an entry point into ongoing use, not a finish line?

Then make one change that reduces control but increases capability. Not a redesign. One change.

The goal isn’t to remove guidance.

It’s to stop confusing guidance with engagement.

What to do next…

It’s tempting to believe that if we just design the path well enough, users will behave “correctly.”

But long-term engagement rarely comes from being guided.

It comes from being enabled.

When you build platforms, you stop asking how to push users forward—and start asking what kind of system is worth staying in.

- On Generative Features by Stephen Anderson

- From Paths to Sandboxes conference talk [video] by Stephen Anderson

- Just-in-Time Adaptive Influence by Anders Toxboe

- Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Anders Toxboe

- Autonomy Bias by Anders Toxboe