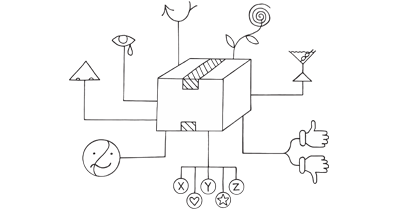

How: Send a package with diaries, cameras, and maps to participants, along with instructions for unsupervised tasks. They independently record their daily lives, providing insights in a natural, unguided setting. This method captures authentic experiences and deepens user empathy.

Why: Cultural probes allow for a deeper understanding of the user's environment, behaviors, and motivations, providing unique insights for empathetic and user-centered product design.

Cultural Probes are a qualitative research method designed to inspire ideas and insights in the early stages of design. Rather than seeking definitive answers or statistically valid data, Cultural Probes are used to evoke personal responses, emotions, and reflections that reveal the lived experiences of users. Their strength lies in the unexpected—uncovering subtle cultural values, personal narratives, and unarticulated needs that are often invisible in structured interviews or surveys.

Originally developed in 1999 by Gaver, Dunne, and Pacenti, the method has roots in both design research and artistic exploration. Cultural Probes challenge traditional empirical approaches by embracing ambiguity, curiosity, and creative engagement with participants.

What are Cultural Probes?

A Cultural Probe typically consists of a physical or digital kit filled with carefully selected artifacts and evocative tasks. These may include postcards with open-ended questions, disposable cameras, diaries, maps, stickers, or simple writing prompts. Participants complete the tasks over time, documenting their environments, thoughts, or behaviors in ways that invite reflection and storytelling.

The intention is not to gather clean, comparable data sets, but to create space for participants to express their identity and worldview in a subjective, expressive manner. This makes the outputs more poetic than scientific, but incredibly powerful for driving human-centered design.

Cultural Probes are particularly useful at the beginning of a design process when designers are still exploring the problem space. They are well-suited for:

- Gaining empathy for people’s lives, routines, and emotions

- Exploring difficult-to-access or highly personal contexts

- Generating inspiration rather than validation

- Situations where conventional observation is intrusive or impractical

Designers use the insights from Cultural Probes to build richer personas, spark concept development, or challenge assumptions about user behavior.

Designing a probe kit

The success of a Cultural Probe depends largely on how well the kit is designed. Tasks should be playful, open-ended, and intentionally ambiguous to encourage unexpected responses. For example, instead of asking, “What do you do in the morning?”, a probe might say, “Photograph the first object you touch when you wake up.” This subtle shift invites interpretation, storytelling, and emotional connection.

Researchers must also balance effort and engagement. A well-crafted kit is visually appealing and easy to navigate, while not demanding excessive time or effort from participants. Drawing from the work of Thoring et al., good probe design considers the tradeoff between effort (preparation, participation, and evaluation) and the value of insights it might reveal.

Modern implementations have extended the traditional format of Cultural Probes. Examples include:

- TaskCam. A digital photo capture tool with embedded prompts

- VisionCam. A motion-triggered image recorder for capturing environmental rhythms while preserving privacy

- Automatic Interviewer. A device that verbally prompts participants and records spoken responses

Probes have also been categorized into types, such as empathy probes (for emotional insights), technology probes (to test digital interactions), and reflective probes (to capture introspection).

These variations allow researchers to tailor their approach to specific contexts, whether domestic, urban, mobile, or educational.

Why use cultural probes?

The value of Cultural Probes lies in their ability to capture emotional depth and contextual richness. They help uncover what users might not know how to say directly, offering a glimpse into the tacit and the symbolic. However, this richness comes at a cost.

Cultural Probes are not meant for structured data collection or comparative studies. Their results are hard to analyze systematically, and participant engagement can vary. The method is also vulnerable to misinterpretation if not contextualized carefully during synthesis.

Because of these limitations, Cultural Probes are best seen as one part of a broader research strategy. They are excellent for inspiring early design but should be followed up with complementary methods like interviews, usability testing, or contextual inquiries for validation.

What are cultural probes good for?

Analysis of Cultural Probe outputs is interpretive. Designers look for metaphors, recurring themes, or emotionally resonant moments. Instead of coding responses as in traditional qualitative research, probe analysis leans into synthesis—storyboarding, mapping, or even collaging the findings.

These outputs are often shared as artifacts themselves, serving as conversation pieces with stakeholders or creative triggers in ideation workshops. The subjective nature of the material invites diverse interpretations and promotes a richer, more empathetic dialogue within design teams.

Cultural Probes remain a valuable and inspiring method in user-centered design. While they do not provide clear-cut answers, they offer something more elusive: a doorway into people’s everyday lives, seen through their own eyes. When thoughtfully designed and used with care, Cultural Probes can reshape how teams understand users and approach innovation—not through data points, but through deeply human stories.

Measuring the evidence strength of Cultural Probes

The effectiveness of Cultural Probes is typically measured by the number of ideas generated and tasks completed. Given the subjective nature of the data, it’s crucial to interpret the results with care. The goal is not to make definitive conclusions, but to gain a deeper understanding of the user’s world and generate innovative ideas for product design.

Remember, the ultimate success of using Cultural Probes lies in the empathy and deep understanding you gain about your users, which can lead to designing products that truly meet their needs and fit into their lives.

Popular tools

The tools below will help you with the Cultural Probes play.

-

TaskCam

A custom-built digital camera with built-in task prompts. Participants scroll through prompts and capture related images. Designed to replace disposable cameras and label tags traditionally used in Cultural Probes.

-

VisionCam

A computer vision-based tool that captures abstracted time-lapse images in response to movement. Designed to preserve privacy while capturing ambient environmental rhythms for long-term cultural context.

-

Automatic Interviewer

A standalone device that plays recorded prompts and captures spoken responses from participants. It supports natural, in-situ audio reflection and is especially useful where a researcher cannot be present.

-

Indeemo

A mobile ethnography platform where participants complete visual and written diary tasks using their smartphones. Excellent for creating open-ended, flexible prompts similar to digital Cultural Probes.

-

Dscout

Allows researchers to deploy remote diary studies and multimedia prompts. Participants capture videos, photos, and reflections, making it ideal for virtual Cultural Probe implementations.

-

EthOS

Supports longitudinal research through mobile diaries, multimedia entries, and task-based guidance. Can be customized for Cultural Probe-style tasks across different contexts.

-

ExperienceFellow

Enables participants to log experiences with contextual photos, videos, and notes over time. Built for service design and experience documentation—aligns well with the principles of Cultural Probes.

Real life Cultural Probes examples

IKEA

IKEA used cultural probes to understand diverse lifestyle needs, influencing their furniture design and marketing strategies for different global markets.

Sony

Sony employs cultural probes in product design, capturing unique user behaviors and preferences, contributing to innovative consumer electronics tailored to lifestyle needs.

Philips Design

Philips Design initiated the ‘Design Probes’ program to explore future socio-cultural and technological trends. By employing cultural probes, they gathered insights into potential future user needs and behaviors, informing the development of innovative product concepts.

Source: philips.com

Design Council UK

The Design Council employed cultural probes in educational settings to gain insights into the experiences of students and educators. This approach informed the design of more effective and engaging learning environments.

Source: designcouncil.org.uk

A collection of clever product discovery methods that help you get to the bottom of customer needs and coining the right problem before building solutions. They are regularly used by product builders at companies like Google, Facebook, Dropbox, and Amazon.

Get your deck!Related plays

- Design: Cultural Probes by Bill Gaver, Tony Dunne, and Elena Pacenti at ACM Interactions

- Opening the Cultural Probes Box: A Critical Reflection and Analysis of the Cultural Probes Method by Katja Thoring, Carmen Luippold, and Roland M. Mueller at 5th International Congress of International Association of Societies of Design Research (IASDR)

- Cultural Probes at Wikipedia

- Probes and Participation by Connor Graham and Mark Rouncefield at Proceedings of the 2008 Participatory Design Conference

- Reflective Probes, Primitive Probes and Playful Triggers by Daria Loi at Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings

- Cultural Probes and the Value of Uncertainty by William W. Gaver, Andrew Boucher, Sarah Pennington, and Brendan Walker at ACM Interactions

- Cultural Probes – an experimental method for research insight by Malene Lyng Jørgensen, Lori Webb, and Kikki Nielsen at IT University of Copenhagen