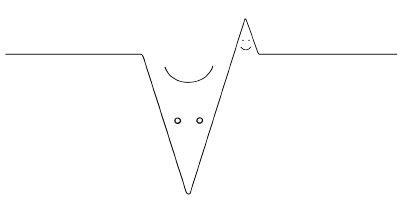

Negativity bias is the psychological tendency for negative events, experiences, or information to have a greater effect on one’s psychological state and processes than neutral or positive things. In essence, individuals tend to pay more attention to, learn from, and use negative information far more than positive information.

Negativity bias is a powerful force that shapes our perceptions and memories. Imagine you recently had lunch with two friends. One friend had a pleasant but forgettable experience, while the other had a minor mishap with their food. Later that day, when someone asks you about lunch, you will be more likely to recall the negative details about her friend’s meal, even though the overall experience for both friends was likely positive.

This human tendency extends to the digital world as well. Let’s say you are browsing an e-commerce site for a new pair of shoes. You find a pair you like, but while scrolling through the product page, you notice a single negative review mentioning a sizing issue. This negative information is likely to loom larger in your mind than the several positive reviews praising the shoe’s comfort and style. This is because the negativity bias can cause us to place a greater weight on negative information when making decisions, even if it’s outweighed by the positive aspects.

The study

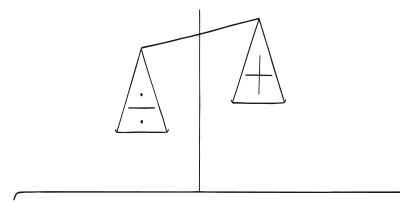

One of the most influential studies on negativity bias was conducted by Rozin and Royzman in 2001. This research explored the psychological mechanisms underlying the negativity bias and provided empirical evidence supporting the idea that negative events have a greater impact on an individual’s psychological state than positive events of the same intensity. Their experiments showed that in various scenarios, such as evaluating job candidates based on positive versus negative traits, or tasting pleasant versus unpleasant foods, participants’ responses were more strongly influenced by the negative aspects. For instance, a single negative trait in a job candidate’s profile had a greater impact on the evaluative judgment than several positive traits, illustrating the powerful sway of negative information.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296-320.

Our brains are wired to prioritize negative experiences. This evolutionary trait served as a survival mechanism, helping us avoid danger. However, in today’s world, negativity bias can influence our decision-making and perceptions in various ways.

Negativity bias isn’t just a hunch; it’s a well-established psychological phenomenon with demonstrably powerful effects. This bias is rooted in the fundamental principle of survival negativity. Evolution has shaped our brains to prioritize negative information as a matter of survival. Ancestrally, recognizing and avoiding dangers like predators or poisonous plants held a higher priority than focusing on pleasant but inconsequential experiences. This negativity bias became ingrained in our cognitive processes, influencing how we perceive, learn from, and react to information in the modern world.

The principle is further supported by findings in cognitive psychology, which demonstrate that negative emotions generally involve more thinking and the information is processed more thoroughly than positive ones. This heightened cognitive processing makes unpleasant experiences more memorable and influential on our future behavior and decision-making. For example, the memory of touching a hot stove causes an immediate and lasting impression that warns against repeating the action.

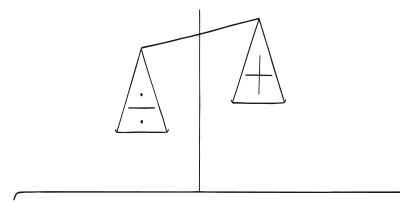

Behavioral economics also examines negativity bias through the lens of loss aversion, where the displeasure of losing is psychologically more impactful than the pleasure of gaining something of equivalent value. This principle explains why negative experiences such as financial losses can have a disproportionate effect on consumer behavior and risk assessment.

In social psychology, negativity bias helps explain phenomena such as the tendency for bad first impressions to be more lasting than good ones, or for negative rumors to spread more quickly and be harder to dispel than positive information. These tendencies can have significant implications for interpersonal relationships and group dynamics, influencing everything from personal reputations to the success of businesses.

Common mistake applying the Negativity Bias include:

- Overemphasis on fear

Overusing negativity can lead to fear fatigue, where the audience becomes desensitized to warnings, reducing the effectiveness of the message. - Neglecting positive follow-up

Focusing solely on negative aspects without offering a positive resolution or benefits can alienate the audience and foster negative associations with the brand. - Misjudging audience tolerance

Different audiences have varying thresholds for negative content. Misjudging this can either overwhelm the audience or fail to make a significant impact. - Unclear or deceptive framing

Don’t mislead users with manipulative language. Transparency builds trust. - Ignoring user needs

Negativity bias is a tool, not a replacement for understanding core user needs. Prioritize solving user problems.

Designing products using the Negativity Bias

This bias can be leveraged to enhance user engagement by emphasizing the prevention of negative outcomes rather than just promoting positive features.

In product design, it is effective to highlight the problems your product solves, especially in high-stakes areas like security software or health products. By outlining the severe consequences of inaction, such as data breaches, you can tap into the user’s innate desire to avoid negative outcomes, making the product more appealing and memorable.

Benefits should be framed as solutions to user pain points. For example, instead of promoting “fast loading times,” reframe it as “avoid frustrating website delays.” This method utilizes negativity bias by focusing on alleviating negative experiences, thereby making the solution more compelling.

Incorporating social proof like user testimonials that acknowledge initial concerns and show how the product resolved them can build trust and resonate more deeply with potential customers. It demonstrates the product’s effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

Scarcity tactics can also incorporate negativity bias. Rather than simply stating that a product is in limited supply, emphasize what the customer stands to lose, such as “don’t miss out on this opportunity to avoid [negative consequence],” to increase urgency and compel action.

Additionally, design elements like progress bars can remind users of what is at stake without proper action. For instance, a backup software might indicate how much time and resources could be lost without proper backup, nudging users towards completing the desired action.

It is crucial to manage first impressions by designing intuitive and error-forgiving interfaces from the start. Any errors should be met with helpful feedback to prevent initial negative experiences from defining the user relationship.

Handling customer feedback requires understanding negativity bias. Encouraging balanced feedback involves actively soliciting positive reviews and addressing negative feedback promptly and constructively to maintain a favorable public perception.

In marketing, emphasizing how a product prevents negative outcomes can be more persuasive than focusing solely on benefits. For example, highlighting how security features protect against losses can be more effective than detailing technical specifications.

Transparency about potential downsides and providing risk information clearly are vital. Offering guarantees or free trials can mitigate perceived risks, demonstrating confidence in the product.

Anticipating user concerns by using microcopy strategically to guide and reassure users, crafting well-toned error messages, and interspersing delightful interactions can transform potentially negative experiences into positive ones, ensuring user satisfaction.

Ethical recommendations

While this can be a powerful tool in guiding user behavior and decision-making, there is a significant risk of misuse. If applied without careful consideration, negativity bias can lead to fear mongering, where users are manipulated into making decisions out of fear rather than informed judgment. This tactic can cause unnecessary stress or anxiety, particularly if users are made to feel constantly at risk or in danger without just cause. For example, overemphasizing the potential dangers of not using a product or service might push users into purchases they don’t need or can’t afford, exploiting their natural inclinations to avoid negative outcomes.

Here are examples of potential misuses:

- Fearmongering

Exaggerating negative consequences or creating unnecessary anxieties to pressure users into action can be manipulative and unethical. - Deception

Misleading users about potential drawbacks or obscuring risks behind a veil of negativity can erode trust and damage user experience. - Exploiting vulnerabilities

Preying on users’ insecurities or anxieties to make a sale is not only unethical but can also backfire, fostering resentment and brand aversion.

To ensure that negativity bias is used ethically and remains user-centric, consider the following best practices:

- Be transparent

Be upfront and honest about potential downsides. This builds trust and allows users to make informed decisions. - Provide balanced information

While it can be effective to highlight negative outcomes to motivate certain behaviors, always balance this with positive information. Users should feel informed, not manipulated. This approach helps to establish trust and fosters a more positive user experience. - Offer real solutions

When presenting users with problems or risks, always accompany these challenges with genuine, effective solutions. Frame negativity bias around the positive outcomes your product offers. Highlight how it helps users avoid negative experiences. This not only helps to prevent anxiety and fear but also empowers users to take constructive action. - Respect user autonomy

Allow users to make their own decisions without undue pressure. Empower them with information and clear choices, allowing them to weigh potential benefits and drawbacks. This means providing clear, unbiased information that supports a range of outcomes, not just those that benefit the provider. - Educational emphasis

Use negativity bias as a tool for education rather than coercion. Highlighting negative outcomes should be about helping users understand consequences and learn how to avoid them through smart, informed decisions. - Ethical messaging

Be cautious with the language and imagery used. Ensure that all messaging is truthful, avoids exaggeration, and respects the user’s intelligence and context. Misrepresentation can lead to loss of credibility and trust.

While negativity bias can be a persuasive tool, don’t neglect the power of positive emotions. Showcase success stories and the positive outcomes users can achieve.

Real life Negativity Bias examples

Robinhood

The trading app Robinhood uses negativity bias by providing real-time notifications of loss or gain on stocks. By immediately showing the potential financial downside in red, users are prompted to make more cautious and calculated investment decisions, highlighting the risks involved in trading.

Grammarly

Grammarly incorporates negativity bias by highlighting errors in text as users type. The design uses red underlines to draw attention to mistakes, creating a visual cue that taps into users’ fears of appearing unprofessional or making embarrassing writing errors. This design not only corrects user errors but also educates them on better writing practices.

Dropbox

Dropbox effectively uses negativity bias in its product design by emphasizing the risks associated with not backing up files. The product features notifications and reminders about unsaved changes or unsynchronized files, subtly reminding users of the potential negative outcomes of data loss to encourage continuous syncing and backup.

Trigger Questions

- What potential negative outcomes can our product help users avoid?

- Are we balancing our use of negative information with positive solutions?

- Can we reframe product features to emphasize solutions to user pain points?

- Are we prioritizing essential negative information that truly aids users?

- How can we transform potential negative interactions into positive experiences for users?

- How do we ensure that our emphasis on negative aspects does not overshadow the value of our product?

- What are the potential emotional impacts of the negative messages on our audience?

- Are there clear, positive calls to action following the negative messages?

- Have we considered cultural differences in the perception of negative messaging?

Pairings

Negativity Bias + Social Proof

Social proof, leveraging the influence of others, can amplify the impact of negativity bias. For instance, highlighting negative customer reviews overcome by the product, showcasing how the product addressed the concerns, can be more persuasive than just positive testimonials. For example, Yelp reviews showcasing a restaurant’s initial service issues followed by glowing praise after the problems were resolved

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

Negativity Bias + Authority Bias

People tend to trust authority figures. Combining negativity bias with authority bias can be effective. For instance, a health app might showcase endorsements from medical professionals alongside warnings about the dangers of ignoring certain health risks.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We have a strong tendency to comply with authority figures

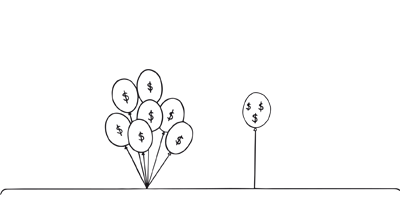

Negativity Bias + Loss Aversion

Negativity bias and loss aversion together create a powerful influence on decision-making. For instance, in financial services apps, emphasizing the potential financial loss from not investing (negativity bias) alongside the benefits of saving due to higher interest rates (loss aversion) can motivate users to act more conservatively with their finances.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Negativity Bias + Scarcity Bias + Loss Aversion

Limited-time offers, a form of scarcity, can be even more compelling when framed around avoiding negative outcomes. For instance, a financial planning service might emphasize the potential negative consequences of not starting to invest today, rather than simply highlighting the limited availability of a free consultation.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We value something more when it is in short supply

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

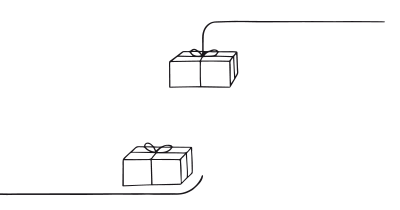

Negativity Bias + Reciprocity

People feel obligated to return favors. Offering users a free trial or a valuable resource can trigger reciprocity, making them more receptive to addressing potential negative consequences highlighted later. For instance, a security software company might offer a free security scan to identify vulnerabilities, then emphasize the potential risks of not addressing the identified issues.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We feel obliged to give when we receive

Negativity Bias + Salience

Certain design elements stand out more than others. Use salience to draw attention to negative information you want users to focus on, but ensure it aligns with the overall user experience and doesn’t feel manipulative. For instance, a website highlighting data privacy concerns might use a bold red banner to frame the potential consequences of not using strong passwords.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

Our decisions are shaped by the data presented to us

Negativity Bias + Storytelling

Stories can be a powerful persuasive tool. Weaving negativity bias into a narrative can be particularly effective. For instance, a public health campaign might share a story about someone who suffered negative consequences due to vaccine hesitancy, alongside information about the benefits of vaccination.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We engage, understand, and remember narratives better than facts alone

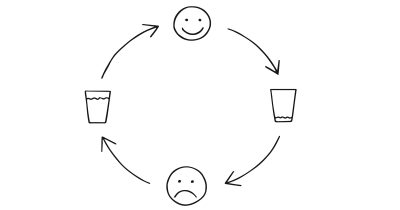

Negativity Bias + Feedback Loops

Incorporating feedback loops with negativity bias involves providing immediate feedback on users’ actions that might lead to negative outcomes. For example, a fitness app that tracks dietary habits could alert users when their eating patterns may lead to undesirable health results, encouraging immediate corrective action.

We recall unpleasant events better than positive ones

We are influenced by information that provides clarity on our actions

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Bad is stronger than good by Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer & Vohs

- Negativity bias by Rozin & Royzman

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323-348.

- Lerner, J. S., Small, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2004. The effect of prospect theory on risk preference. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 53(1), 161-173.

- Raghubir, P., & Menon, G. (2007). The endowment effect and framing in risky decision-making. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(2), 461-473.

- Ito, T. A., Larsen, J. T., Smith, N. K., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1998). Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 887-900.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Gardner, W. L. (1999). Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 191-214.

- Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296-320.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226.

- Festinger, Schacter & Back (1950). Social pressures in informal groups: A study of a housing community. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.