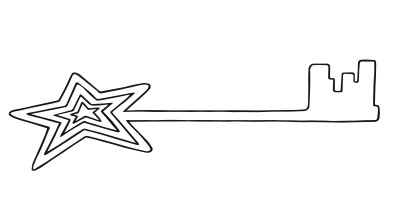

Persuasive Patterns: Restructuring

Loss Aversion

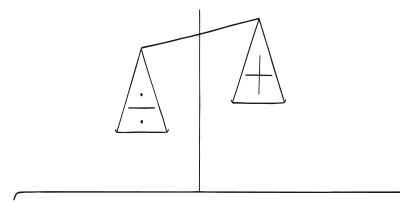

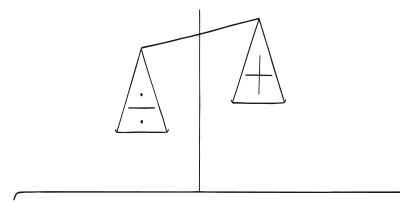

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Loss Aversion refers to people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains. It’s the pain of losing something perceived as twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining something of equal value.

Imagine a person at a local market, deciding whether to buy a handcrafted vase. They are told that the vase was originally priced at $50 but is now on sale for $30. The perceived “loss” of not capitalizing on the $20 discount feels more significant than the actual gain of acquiring the vase for $30. This individual is more motivated to make the purchase to avoid the feeling of loss associated with missing out on the discount, even if they didn’t initially intend to buy the vase.

Consider a user of a stock trading app. They invest in a particular stock, hoping for a profit. Over time, they notice that the stock’s value has decreased by 5%. The emotional impact of this loss feels much more profound than the satisfaction they would have felt if the stock had increased by 5%. This disproportionate emotional response to losses compared to gains can influence their future trading decisions, making them more cautious or even leading them to sell the stock prematurely.

The study

In 1979, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky introduced a groundbreaking concept that would challenge traditional economic theories: the “Prospect Theory.” Their research highlighted that people do not always act rationally when making decisions under risk. Instead of evaluating outcomes based on their absolute final states, individuals often consider potential gains and losses relative to a reference point. One of the most striking findings was that losses generally have a more significant emotional impact than equivalent gains, a phenomenon termed “loss aversion.” This means that the pain of losing something is often felt more intensely than the pleasure of gaining something of equal value. Their work also revealed that individuals tend to overweigh the probabilities of infrequent events, leading them to sometimes make decisions that might seem irrational when viewed through the lens of traditional economic theories.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

Kahneman and Tversky’s research sought to better understand the anomalies and contradictions in human decision-making, especially when it came to choices involving risk. The discovery of Loss Aversion marked a significant departure from traditional economic theories, which often assumed humans made rational decisions based solely on potential outcomes.

Loss Aversion stems from the broader principle of Prospect Theory, which describes how people decide between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk. The central tenet is that losses loom larger than gains, influencing decision-making in a way that might not always be considered “rational.”

Rooted in behavioral economics, Loss Aversion highlights a fundamental aspect of human psychology where individuals demonstrate a greater emotional impact from a loss than from an equivalent gain. For instance, the displeasure from losing $10 is more intense than the pleasure of finding $10. In product design and marketing, leveraging this principle means that users are often more motivated by the thought of losing out on something than by the thought of gaining something equivalent.

Loss aversion, a foundational concept in behavioral economics, posits that people feel the pain of losses more acutely than they feel the pleasure of equivalent gains. This principle underpins several other behavioral patterns. The Endowment Effect, for instance, is a direct offshoot, describing how people assign higher value to items they own, fearing the loss they’d experience if they parted with them. The Status-Quo Bias emerges from a preference to maintain current states, driven by the innate desire to avoid potential losses that changes might bring. Our Scarcity Bias is intrinsically tied to the fear of missing out on limited resources, making the potential loss seem much more significant. Sunk Cost Bias encapsulates the reluctance to abandon pursuits due to resources already invested, as individuals grapple with the perceived “loss” of those resources. The Decoy Effect operates on relative valuation, often influenced by framing in the context of potential gains and losses. Commitment Devices, too, are mechanisms people use to lock themselves into future actions, aiming to sidestep potential future losses. Each of these patterns, in their unique ways, can be traced back to the human psyche’s disproportionate weighting of losses relative to gains.

Designing products using Loss Aversion

When framing product features or choices, emphasis can be subtly shifted to highlight what users stand to lose rather than just the benefits they might gain. If a user is considering an upgrade, rather than only emphasizing the additional features of the premium version, designers could also indicate what will be unavailable or limited in the basic version. This approach pivots the decision-making process, tapping into the user’s innate desire to avoid potential losses.

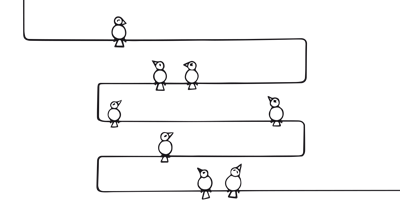

User interfaces can be designed to provide gentle reminders at critical decision points. Consider a scenario where a user is on a trial version of software. As the trial period nears its conclusion, timely notifications can be introduced, highlighting the features they’ve grown accustomed to and might lose access to if they don’t upgrade.

When integrating visuals, consider diagrams or side-by-side comparisons that clearly delineate what users stand to gain and what they might miss out on. Such visual aids can provide an at-a-glance understanding, making decision-making more straightforward for the user.

Examples of powerful ways to apply Loss Aversion in designs are:

- Framing Choices

During the decision-making process, frame users’ choices as either a potential gain or a potential loss. This framing taps into their inherent loss aversion, guiding their decisions. - Free trials

Offer users free trial periods. Many people are more inclined to engage in free trials than to pay upfront. Once invested in the trial, they may be more likely to pay to avoid losing what they’ve experienced or achieved during that trial. - Discounts and paid trial periods

Utilize discounts and trial periods to instill a fear of missing out. Users might purchase a discounted product fearing they’ll lose out on the savings, or they might engage more with a product during a trial period to avoid losing their progress when the trial ends. - Delay Payments

Postpone the moment users have to make payments or subscription fees. This shift can make users see the decision not as paying for a product but as avoiding losing access to it. - Immediate problem handling

Address issues as soon as they arise. The emotional impact of a loss grows over time, so replacing a faulty product or service immediately can mitigate this negative effect. Offer an identical or even superior model as a replacement. - Distribute good news

Instead of providing all the positive information or rewards at once, space them out over time. A series of smaller successes or benefits often feels more valuable to users than one large one. - Lazy registration

Allow users to engage with a product before requiring registration. After they’ve invested time and effort, they’re more likely to register to avoid losing their progress or customizations. - Understand the sunk cost dilemma

Recognize that users don’t want to “waste” their resources, whether that’s time, effort, or money. Once they’ve invested in something, they’re more likely to continue investing to avoid feeling that their initial investment was wasted.

Ethical recommendations

Loss aversion, being a deeply ingrained human tendency, can be exploited in ways that might not serve the best interests of users. Some businesses might employ it to create artificial pressure on consumers, compelling them to make impulsive decisions. Subscription models, for instance, might offer trial periods and then rely on loss aversion to make it challenging for users to cancel, emphasizing what they stand to “lose” if they do. In digital platforms, the design can emphasize the loss of digital assets, streaks, or progress, even when continuing might not be in the user’s best interest. Such strategies can lead users to make decisions that are not necessarily beneficial for them, driven by the fear of loss rather than genuine value.

While it’s natural to highlight benefits, give users ample time and resources to make informed decisions. For instance, in trial offers, remind users well in advance of any upcoming charges or changes.

If a user wants to leave a service or discontinue a product, make the process straightforward. Don’t hold users hostage to their past commitments or actions.

Real life Loss Aversion examples

Gym Memberships

During promotional trial periods, members can access all facilities and get accustomed to the benefits of the gym. As the promotional period ends, members are reminded of the benefits they’ve been enjoying – from state-of-the-art equipment to group classes – and what they would miss out on without a full membership. The potential loss of fitness progress and amenities can lead to members transitioning to the full-priced membership.

Netflix

Before announcing any subscription price increases, Netflix sends notifications alerting users about the impending change. By giving them a window of opportunity to enjoy the current prices and highlighting the content they love, Netflix creates a strong sense of potential loss. This tactic nudges users to renew or even upgrade their subscriptions, hoping to lock in at existing rates before the increase.

Headspace

Headspace, a meditation app, offers a series of guided sessions. As users progress and unlock more advanced meditation tracks, missing a day or two might prompt notifications mentioning the potential setback in their mindfulness journey. The idea of losing progress or breaking the routine can motivate users to maintain consistent usage and possibly invest in a subscription for uninterrupted access.

Trigger Questions

- What areas in the design might induce a feeling of loss for the user?

- How is the value, and potential loss of that value, clearly communicated to the user?

- Is the design inadvertently pressuring users to make decisions out of fear of loss?

- Is the potential loss presented to the user genuine, or is it artificially constructed?

- How transparent and straightforward is the communication of potential losses and gains?

- If users decide to opt out or change their decisions, how easily can they do so?

Pairings

Loss Aversion + Limited Choice

Pronounce the potential perceived loss. If there are only a few options available and one of them is about to be unavailable or altered in some way, the fear of missing out on that particular option becomes more significant. The limited number of choices amplifies the value of each option, making the potential loss feel even more substantial.

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

Loss Aversion + Commitment & Consistency

Highlighting the loss of not following through after an initial commitment, can be powerful.

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

Loss Aversion + Simulation

Combining loss aversion with simulation can be a potent mix. For example, consider a financial planning app that uses simulation to project future savings. If the app shows users the potential loss of retirement funds if they don’t start saving now, it taps into loss aversion. Users feel the potential loss more acutely and may be motivated to act. Simulating the future state and highlighting the potential loss makes the abstract concept of future savings more tangible and emotionally resonant.

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Give people first-hand insight into how inputs affect an output

Loss Aversion + Unlock Features

Many software applications or games use the strategy of unlocking features as users progress or achieve certain milestones. When combined with loss aversion, this could involve providing users with access to premium features for a limited time. Once users get accustomed to these features, taking them away (or locking them again) plays on their aversion to loss, potentially motivating them to upgrade or make a purchase to regain those features.

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Reward specific behaviors by enabling new capabilities

Loss Aversion + Status

In platforms that employ user statuses or rankings, loss aversion can be a powerful motivator. Users who achieve a particular status or rank do not want to lose it. For instance, in a community or forum where users are ranked based on their contributions, showing that a user’s status might drop due to inactivity can spur them into action. The potential loss of status, and the privileges or recognition that come with it, can be a strong driver of engagement.

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

We constantly look to how our actions improve or impair how others see us

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty by Kahneman & Tversky

- Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk by Kahneman & Tversky

- Loss Aversion

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1039-1061.

- Thaler, R. H., Tversky, A., Kahneman, D., & Schwartz, A. (1997). The effect of myopia and loss aversion on risk taking: An experimental test. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 647-661

- Thaler, R. H (1999). Mental Accounting Matters. From Choices, Values, and Frames edited by Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- Fryer et al. (2012). Enhancing the efficacy of teacher incentives through loss aversion: a field experiment. NBER Working Paper No. 18237.