Persuasive Patterns: Obligation

Sunk Cost Bias

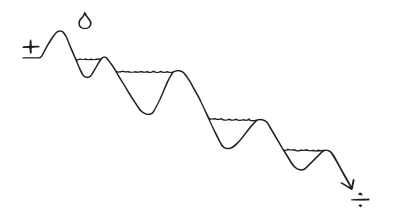

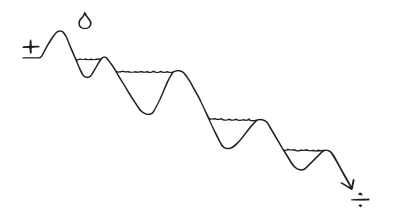

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

The sunk cost bias is the tendency to continue investing in a decision or project based on prior investments, even when future benefits do not justify further commitment.

Imagine someone who attends a movie theater to watch a film they’ve been eagerly anticipating. Twenty minutes into the film, they find it uninteresting and not at all what they expected. Although the individual realizes they would rather leave and do something more enjoyable, they decide to stay. The rationale behind their decision is that they’ve already spent money on the ticket, and leaving would mean they “wasted” that money, even though staying doesn’t change the fact that the money has been spent.

Similarly, consider a user who subscribes to an online course platform. They begin a lengthy course, but after progressing through the initial modules, they find the content isn’t suited to their learning style. However, they’ve already invested several hours into the course, and even though there are other courses on the platform that might be a better fit, they decide to stick with the initial course. The thought of having “wasted” those hours if they switch to a different course keeps them committed, even though the time spent cannot be recovered, and they might benefit more from a course better tailored to their needs.

The study

In a seminal study, researchers investigated the phenomenon of people attending a theater performance. Participants were given tickets to a play, with some paying full price and others receiving a substantial discount. Midway through the play, it became evident that the performance was subpar and not enjoyable. Yet, those who paid full price were significantly more likely to stay and watch the entire play compared to those who received a discount. The invested cost (in this case, the ticket price) influenced their decision to stay, even when they weren’t enjoying the experience.

Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124-140.

The sunk cost bias operates on the principle of loss aversion, a key concept in behavioral economics. Individuals tend to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains. When faced with the perception of a potential loss (like the loss of money already spent), individuals often make irrational decisions to avoid realizing that loss, even if it leads to more significant losses in the future.

The concept of sunk costs dates back to traditional economic theories, where they were considered costs that should not impact future decision-making since they cannot be recovered. However, in the realm of behavioral economics and psychology, researchers began observing that people frequently consider sunk costs in their decisions, leading to the identification and naming of the “sunk cost bias” in the late 20th century.

Designing products with the Sunk Cost Bias

Users are more likely to continue with a service or product if they feel they’ve already invested significantly into it. In the digital realm, designers can subtly remind users of the time or effort they’ve already dedicated. For instance, a language learning app might remind users of the streak they’ve maintained or the number of lessons completed. This can be a powerful motivator for users to continue, driven by the desire not to lose their invested effort. Furthermore, subscription models can also play on this bias; when users have paid for a year upfront, they’re more likely to engage with the service throughout the year, even if only to feel they’re getting their money’s worth.

When integrating the sunk cost bias into product design, consider creating features that allow users to invest time and effort, thereby increasing their perceived value and connection to the product. For instance, platforms that enable users to customize their interface, set up intricate profiles, or curate personalized content can effectively capitalize on this bias. As users invest more time in these customizations and personalizations, they’re more likely to remain engaged with the platform, feeling that their efforts would be “wasted” if they were to leave.

Incorporating the Sunk Cost Effect into design isn’t about trapping users but rather about amplifying the value they receive from their investments. Below are specific strategies for how to use the Sunk Cost Bias in design:

- Enhance upselling opportunities

Recognizing that users who’ve already committed to a subscription or service are more prone to further investment is key. Design interfaces that subtly highlight premium features or additional services can entice users to upgrade. For instance, a cloud storage solution might show users how much space they’re using and suggest upgraded plans for more storage. Given that they’re already invested, they’re more likely to consider expanding their plan. - Encourage consistent usage

When users pay for access, they inherently want to maximize their return on that investment. Design experiences that make the utilization of paid features easy and intuitive. For a fitness app, this could mean offering personalized workout schedules or diet plans for premium members, ensuring they feel the value of their subscription. - Proactive reminders

Avoiding cancellations or ensuring attendance is a common challenge, especially for events or services. By sending timely reminders that emphasize the value or uniqueness of the booked event, users are nudged to either commit to attending or consider transferring their spot to someone else. This not only decreases last-minute drop-outs but also maintains a positive brand perception. - Post-sale engagements

The user’s journey doesn’t end post-purchase. Design post-sale engagements that remind them of the value they’ve attained and present complementary offerings. For instance, if a user has bought a high-end camera, periodic reminders about maintenance checks or offers on compatible accessories can drive post-sale purchases. These touchpoints reiterate the product’s value and open avenues for further investment. - Alleviate buyer’s remorse

The disappointment that arises after a purchase can be mitigated using the sunk cost bias. Products like Hootsuite, for instance, cater to social media marketers who may have made prior investments in strategies that didn’t pan out. By positioning themselves as a solution to rectify past inefficiencies, they appeal to users’ desires to make their past investments worthwhile. - Enhancing form and checkout conversions

Introducing progress indicators in multi-step forms or online checkouts can leverage the sunk cost bias. By showing users how much they’ve already completed, the motivation to finish becomes stronger. The time already spent becomes a driving factor to complete the process. - Loyalty programs and continued purchases

Rewards can be a form of sunk costs. A coffee stamp card, for instance, encourages continued purchases as the user has already made progress towards a free coffee. The prior stamps on the card act as the sunk cost, motivating users to complete the set. - Referral programs

Existing customers, already invested in your product, can be incentivized to bring in new customers through referral programs. Dropbox’s referral program of rewarding both the referrer and the referred (with extra storage space) is a prime example of how sunk cost bias can be leveraged for expanding customer base. - Highlight past investments

Regularly remind users of their past investments, achievements, or progress to instill a sense of pride and commitment, anchoring them to the product or service. - Use milestones

Introduce clear milestones or checkpoints where users can reassess their journey. This can help them decide whether to continue with their current path or make a change. - Reframe past efforts

Encourage a perspective where past efforts, even if they didn’t lead to the desired outcome, are seen as valuable learning experiences. This can reduce the sting of sunk costs and promote a growth mindset.

Ethical recommendations

While it’s beneficial from a business perspective to have deeply engaged users, it’s crucial to ensure that we aren’t trapping or misleading them. For instance, if a platform plans to introduce significant changes or potentially discontinue certain features, it’s essential to communicate this transparently to users, giving them time to adjust and make decisions that best suit their needs. If users have invested heavily in a particular feature, abruptly removing it without adequate notice or support can lead to feelings of betrayal and can erode trust.

When individuals feel heavily invested in something, be it time, money, or effort, they are more likely to continue investing in it, even if it’s not in their best interest. This bias can be exploited in several ways:

- Endless upgrades or add-ons

Companies can push users to continue investing in a product or service by introducing a stream of upgrades or add-ons, making users feel that abandoning now would waste their previous investments. - Subscription traps

Some services may make it difficult for users to cancel their subscriptions, capitalizing on the fact that users might feel they’ve invested too much to simply walk away. - Overemphasis on past investment

Highlighting the amount of time or money users have already invested can pressure them into making further investments, even if they no longer find value in the product or service.

To ensure that you do not fall into any of these trips, the following guidelines can help you:

- Be transparent

Always be transparent about costs, both present and future. If there are potential additional costs or time investments in the future, users should be made aware upfront. - Provide easy exit options

Ensure that users have an easy way to discontinue a service or product. Making it overly complicated or cumbersome to exit can trap users and exploit their sunk cost feelings. - Limit reminders of past investments

While it’s okay to remind users of their progress or achievements, it’s crucial not to overemphasize past investments in a way that pressures them to make further undesired investments. - Prioritize the users’ well being

Always prioritize the user’s needs and well-being. Design products and services that genuinely add value and enhance the user’s experience, rather than focusing solely on prolonging their engagement for profit. - Regular checkpoints

Offer users regular opportunities to evaluate their continued use of a service or product. This can help them assess whether they’re continuing out of genuine interest or merely due to the sunk cost bias.

Real life Sunk Cost Bias examples

eBay

Users who have spent years building up their reputation, feedback score, or even curating watchlists on platforms like eBay might feel more inclined to continue using the platform. The time and effort invested in establishing credibility and customizing preferences make it harder to switch to a new platform, even if it offers similar features.

Duolingo

The language-learning app emphasizes maintaining streaks. As users invest more time and build longer streaks, they are less likely to want to break them, even purchasing “streak freezes” with in-app currency to maintain their progress.

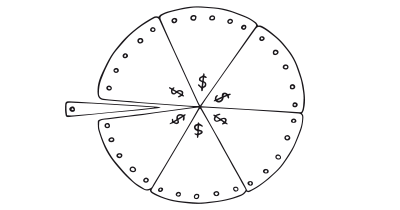

Starbucks

Many coffee shops offer loyalty cards where after purchasing a certain number of drinks, the next one is free. As customers collect more stamps or points, they feel more committed to returning to the same coffee shop to “complete” their card, even if there might be cheaper or more convenient alternatives available.

Trigger Questions

- How have our users already invested in our product, and how can we subtly remind them of this investment?

- What milestones or achievements can we highlight to show users their progress?

- Are there opportunities to create subscription or loyalty models that capitalize on the sunk cost bias?

- How can we balance reminders of past investment with genuine ongoing value?

- Are there points in our user journey where individuals might consider abandoning, and can the sunk cost bias be ethically used to encourage continuation?

- How can we design feedback loops that reinforce the user's commitment and the value they're gaining from their investment?

Pairings

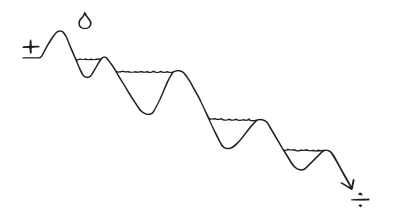

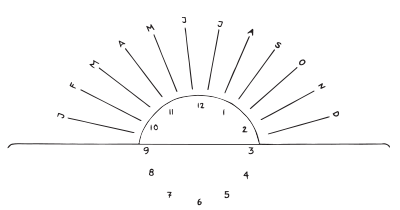

Sunk Cost Bias + Goal-Gradient Effect

As users get closer to achieving a goal, their efforts to reach it can accelerate. Pair this with the Sunk Cost Bias in scenarios like loyalty programs. The more points a user accumulates (and thus the time invested), the more likely they are to make additional purchases to reach the next reward tier.

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

Our motivation increases as we move closer to a goal

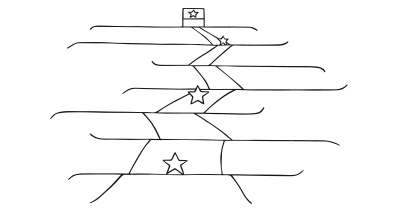

Sunk Cost Bias + Achievements

Earning badges or accolades in a digital platform can signify a user’s progress and investment. The Sunk Cost Bias reinforces the value of these achievements, making users less inclined to switch to a competing service where they’d start from scratch.

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

We are engaged by activities in which meaningful achievements are recognized

Sunk Cost Bias + Commitment & Consistency

Leveraging past investments can drive users to remain consistent with their decisions. When users have invested time, effort, or resources into a product, platform, or service, they are more likely to continue using it to stay consistent with their past choices. For example, designers can introduce features that remind users of their progress or milestones achieved.

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

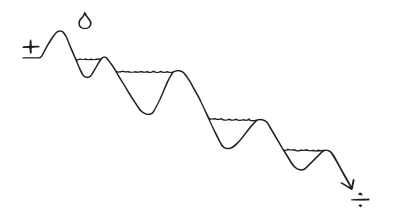

Sunk Cost Bias + Fresh Start Effect + Commitment & Consistency

Periodic fresh starts, like the beginning of a new week or month, can provide an opportunity for users to re-evaluate and let go of past investments that aren’t serving them. While they might be influenced by the sunk cost bias to continue down a less-than-optimal path, introducing a fresh start mechanism combined with reminders of their commitments can help them reassess and decide whether to continue or pivot. For instance, setting “reset” milestones where users reflect and conduct rational analysis allows them to better decide on whether to continue or halt based on measurable outcomes.

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

We are more likely to achieve goals set at the start of a new time period

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

Sunk Cost Bias +

Framing

The way we frame past investments can influence our attachment to them. By presenting past efforts not as wasted but as necessary learning experiences or stages in a larger journey, users can more readily accept changes or redirections. For instance, if a team recognizes that a product built in the past doesn’t meet current needs, reframing the past effort as a valuable learning experience rather than a waste can foster acceptance and openness to new approaches. Emphasizing the idea that every step, even if seemingly backward, is a part of the creative process, can reduce the negative impact of sunk costs and encourage a forward-looking mindset.

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- The psychology of sunk cost by Arkes & Blumer

- Sunk Cost Effect

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy at The Decision Lab

- Sunk cost at Wikipedia (en)

- Staw, B. M. (1976). Knee-deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(1), 27-44.

- Garland, H. (1990). Throwing good money after bad: The effect of sunk costs on the decision to escalate commitment to an ongoing project. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(6), 728.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Gilbert, D. T., & Ebert, J. E. (2002). Decisions and revisions: The affective forecasting of changeable outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 503.

- Ross, J., & Staw, B. M. (1986). Expo 86: An escalation prototype. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31(2), 274-297.