The Endowment Effect is the psychological phenomenon where individuals ascribe higher value to things they own compared to identical items they don’t own.

Imagine a person who recently acquired a vintage wristwatch from a garage sale. They didn’t think much of it initially, just considering it a stylish accessory. However, after wearing it for a few days, they’ve grown attached to it. One day, a fellow enthusiast offers to buy the watch for a reasonable price. Surprisingly, the owner feels reluctant to part with it, even though they had no particular attachment to it just days before. This change in valuation, where the watch seems more valuable simply because they own it, is a manifestation of the endowment effect. This phenomenon was highlighted in a study where it was found that the endowment effect is not based on factual ownership, but on subjective feelings of ownership induced by physical possession of the object (Reb & Connolly, 2007).

Now, consider a user who has spent considerable time customizing their digital workspace in a project management software. They’ve adjusted settings, organized tasks, and even uploaded personal icons and images. After a while, a new version of the software is released with enhanced features. The user is given an option to migrate to the new version, but they’d have to set up their workspace from scratch. Even though the new version offers better functionality, the user hesitates to make the switch. They feel a strong attachment to their customized workspace, valuing it more than the objective benefits of the new version. This behavior aligns with findings from a study which showed that the endowment effect is stronger for possessions received as gifts or those that have personal value, especially among certain demographics (Jefferson & Taplin, 2011).

The study

In a groundbreaking study by Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler in 1990, the researchers examined the endowment effect in market settings. They conducted several experiments to understand how individuals value items they own compared to items they don’t. One of the most notable experiments involved participants who were given a mug and then offered the chance to sell it or trade it for an equally valued alternative (like pens). The results were telling: those who owned the mugs demanded approximately twice as much to sell the mug as they were willing to pay to acquire one. This demonstrated a clear disparity between the selling price and the buying price, highlighting the endowment effect’s potency.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1990). Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1325-1348.

The endowment effect is rooted in cognitive psychology and behavioral economics. It highlights the cognitive bias where individuals assign greater value to things merely because they own them.

The Endowment Effect stems from the broader principle of loss aversion, where the pain of potential losses weighs more heavily on our minds than potential gains. Essentially, once we own an item, our perception of its worth increases, and the idea of parting with it becomes less attractive. This is not just limited to physical items; it can extend to ideas, achievements, and even relationships. The effect can influence behaviors in various contexts, from the reluctance to trade possessions to hesitation in switching to better services or products because of the perceived “loss” of the current one.

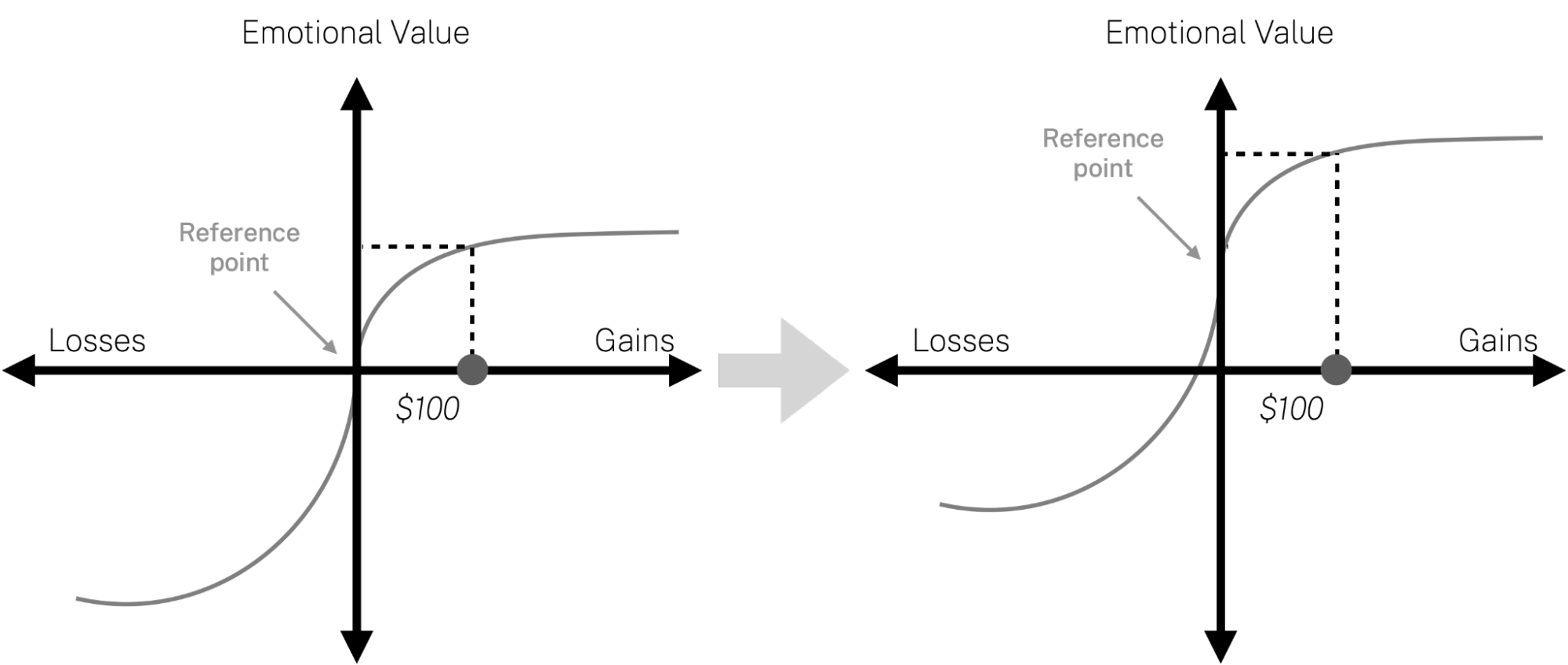

As we get something, we adjust our level of ownership, which becomes the new baseline for how we judge future gains and losses.

The endowment effect posits that once we own something, our valuation of it changes. The mere act of ownership shifts our reference point. This newly acquired item, be it tangible like a car or intangible like a stock option, becomes integrated into our sense of self and our inventory of possessions. This integration establishes a new baseline, a reference point from which we judge future gains and losses. The item we now own is perceived as more valuable than before we owned it, not because its intrinsic value has changed, but because our psychological relationship with it has.

Our fear of losses often drives our choices more than the allure of potential gains. Research suggests that our fear of loss can be twice as potent as our desire for a gain, and sometimes, this disparity is even more pronounced. This means that the potential pain of parting with $100 feels much more intense than the potential pleasure of gaining the same amount.

A direct implication of the endowment effect, stemming from loss aversion, is how we perceive the value of items we own versus those we don’t. When faced with the prospect of giving up a valued possession, the perceived loss associated with parting from it often outweighs the perceived gain of acquiring an equivalent item. This is why, for instance, someone might refuse to trade a concert ticket they own for a sports event ticket of equal market value, even if they enjoy both equally. The potential loss of the concert experience feels more significant than the potential gain of the sports event.

Designing products with the Endowment Effect

Incorporating the Endowment Effect into product design revolves around instilling a sense of ownership among users. By allowing users to personalize or customize features, even in minor ways, they begin to develop a bond with the product. This bond can enhance perceived value, increasing loyalty and engagement. A principle to adhere to is “the more users invest, the more they value.” As users pour time, effort, or even emotional investment into a platform or product, their attachment grows. This investment could be in the form of personal data input, customization, or even time spent learning and navigating the platform. When users feel they’ve put effort into something, they’re more likely to see it as valuable and are less inclined to switch or abandon it. It’s crucial, however, to ensure that personalization and customization options are user-friendly, accessible, and genuinely beneficial.

In the quest to get users to invest in a product to build up a perceived ownership and a feeling of sunk cost, designers can end up overwhelming users with too many customization options upfront, which can be paralyzing and deter engagement. To keep the challenges imposed on users appropriate, it is a more potent strategy to offer personalization incrementally. If users find it challenging or overwhelming to set up an account or make changes, they may feel frustrated, negating any positive effects of the Endowment Effect.

Recognize that once users perceive ownership over something (like a profile, content, or settings), they inherently value it more. This can be leveraged to enhance user engagement and commitment. For instance, allowing users to personalize interfaces or curate content can foster a stronger sense of attachment.

The fear of losing something already owned often outweighs the allure of potential gains. This principle can be used to design user experiences that emphasize what users might lose rather than just highlighting what they could gain. For instance, when users think about discontinuing a service, remind them of the value they’ve built within the platform.

There are a number of specific tactics you can use to employ the Endowment Effect as you design:

- Introduce elements gradually

By gradually introducing features or content and allowing users to become accustomed to them, platforms can create a scenario where users feel they are gaining something valuable. Over time, this can establish a baseline of ownership, making the idea of losing these features more impactful. - Frame choices in terms of loss

When presenting users with choices, frame them in terms of potential losses. This taps into the inherent human tendency to weigh losses more heavily than equivalent gains. For instance, instead of emphasizing the benefits of a premium feature, highlight what users might miss out on if they don’t upgrade. - Emphasize time and effort

Users often value the time and effort they’ve invested in a platform. Highlighting this investment can make the idea of discontinuing use or not progressing to a paid tier more daunting. For instance, remind users of the data they’ve inputted, the settings they’ve customized, or the content they’ve curated. - Offer trial periods

Offering trial periods can be a powerful way to introduce users to a service and establish a sense of ownership. By the end of the trial, the prospect of losing access or features can be a strong motivator for users to continue or upgrade. - Transactional costs vs. value

When offering products or services with trial periods or money-back guarantees, ensure that perceived transactional costs (like the effort of returning a product) are less than the perceived value of using the product or service. This balance can make users more likely to commit. - Money-back guarantees and free return shipping

Recognize that offering such guarantees can increase the likelihood of users taking a chance on a product or service. Once they’ve taken possession or started using it, they’re more likely to view it as valuable and be reluctant to return or discontinue use. - Consider Cognitive Dissonance

When users are faced with decisions that might create internal conflict (like deactivating an account), provide options that can help resolve this dissonance. For instance, offering temporary deactivation instead of complete deletion can reduce the perceived loss and make users more comfortable with their decision. - Long flows as investment

While lengthy forms and onboarding flows might deter some users, they can also be seen as an investment of time and effort. For platforms where accuracy and customization are key, these forms can create a sense of ownership over- and trust in the results or recommendations provided, making users less likely to discontinue use.

Ethical recommendations

By leveraging the Endowment Effect, platforms might unduly emphasize the perceived value of a user’s investments (time, effort, data) to dissuade them from making decisions that might be in their best interest. For instance, discouraging users from leaving a platform or unsubscribing from a service by overemphasizing what they stand to lose.

The Endowment Effect can amplify users’ emotional attachments to virtual goods, achievements, or progress in digital environments. Some platforms might even exploit this by introducing sudden changes or conditions that make users feel they need to spend money or time to preserve what they “own.”

To ensure that your efforts don’t backfire, here is a list to check off as you utilize the Endowment Effect in your designs:

- Provide transparency and clarity

Always be clear and honest with users about the implications of their decisions. If they’re considering leaving a platform or service, provide them with unbiased information about what they stand to lose, without overemphasizing or manipulating their emotions. - Opt-out options

Always give room for escape. Ensure that users have an easy and clear way to opt out or reverse decisions. If they’ve started a process that taps into the Endowment Effect, such as personalizing a product, they should be able to easily revert or change their decision without undue penalties. - Respect user autonomy

Avoid designing systems that trap users by making them feel they’ve invested too much to leave or change their minds.

Real life Endowment Effect examples

When a user attempts to deactivate their account, Facebook invokes the Endowment Effect by displaying messages suggesting that certain friends will miss them. By referencing personal connections, it introduces a sense of potential loss, suggesting that leaving the platform would result in missing out on valuable social interactions.

Zappos

While one-way shipping is common, covering the cost of returns like Zappos is rarer. This strategy encourages users to make purchases they’re unsure about, knowing that returns are hassle-free. Once they possess an item, the notion of returning it and losing it becomes less appealing, even if they were initially uncertain about the purchase.

Stitchfix

Stitchfix employs a unique shopping model where customers fill out detailed style profiles. This investment of time results in personalized clothing selections sent to the user. The act of curating and refining one’s style profile over time deepens the sense of ownership. The more tailored the service becomes to an individual’s preferences, the greater the perceived loss if they were to discontinue the service.

Trigger Questions

- How can we foster a deeper sense of ownership among our users?

- What aspects of our product can users invest time or effort into?

- Are we clearly conveying the value users might lose if they discontinue using our product or service?

- Do we provide avenues for users to personalize or customize their experience?

- How do we ensure that personalization enhances the user experience rather than complicating it?

- Are there tangible or intangible assets users accrue over time that would be lost upon disengagement?

Pairings

Endowment Effect + Commitment & Consistency

Once users have committed to something and shown consistency in their behavior, pairing it with the Endowment Effect can amplify the attachment. For example, in loyalty programs, once users have consistently earned points or rewards (Commitment & Consistency), they might feel more ownership over their accumulated rewards, making them less likely to switch to a competing program.

We value objects more once we feel we own them

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

Endowment Effect + Scarcity Bias

Items that are scarce are perceived as more valuable. When users have one of these scarce items, the Endowment Effect makes them even less likely to part with it. For instance, limited edition products that people manage to purchase often become cherished possessions due to their inherent scarcity combined with the sense of ownership.

We value objects more once we feel we own them

We value something more when it is in short supply

Endowment Effect + IKEA Effect

The IKEA Effect revolves around the increased value people place on products they had a hand in creating. When combined with the Endowment Effect, this value can skyrocket. For instance, custom-designed products or DIY kits where users play a part in the creation or assembly process can make them feel a strong sense of ownership and value towards the end product.

We value objects more once we feel we own them

We place a disproportionately high value on products we helped create

Endowment Effect + Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance arises when there’s a tension or conflict in our beliefs or actions. This discomfort can be amplified when paired with the Endowment Effect, which makes us value things we own more than if we don’t own them. Consider a user who has spent significant time customizing an online profile or space. They believe this space represents a part of their identity. However, they might also feel the platform has some ethical issues they don’t agree with. This creates cognitive dissonance: a conflict between their investment in their profile (amplified by the Endowment Effect) and their personal beliefs.�a�aWhen deciding which patterns to combine with the Endowment Effect, consider which ones naturally align with the user’s journey and the desired outcome. Ensure that one pattern doesn’t overpower the other. For example, if using Scarcity with the Endowment Effect, it’s essential that the product’s scarcity doesn’t overshadow the user’s sense of ownership.�a�aWhile combining patterns can be powerful, overloading users with too many can be counterproductive. It’s essential to be selective and focus on combinations that genuinely enhance the user experience without overwhelming them.

We value objects more once we feel we own them

When we do something that is not in line with our beliefs, we change our beliefs

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Toward a positive theory of consumer choice by Thaler

- Endowment Effect

- Endowment effect at Wikipedia (en)

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1990). Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1325-1348.

- Reb, J., & Connolly, T. (2007). Possession, feelings of ownership and the endowment effect. Judgment and Decision Making.

- Jefferson, T., & Taplin, R. (2011). An investigation of the endowment effect using a factorial design. Journal of Economic Psychology.

- Dommer, S., & Swaminathan, V. (2013). Explaining the Endowment Effect through Ownership: The Role of Identity, Gender, and Self-Threat. Journal of Consumer Research, 39, 1034-1050.

- Ericson, K., & Fuster, A. (2013). The Endowment Effect. ERN: Consumption.

- Morewedge, C. K., & Giblin, C. E. (2015). Explanations of the endowment effect: an integrative review. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(7), 339-348.