Persuasive Patterns: Education

Cognitive Dissonance

When we do something that is not in line with our beliefs, we change our beliefs

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort experienced when one’s beliefs don’t align with one’s actions. This internal contradiction can manifest in various ways, such as craving fast food while wanting to maintain a healthy lifestyle. People often address this discomfort by lying to themselves, changing their behavior, or adopting a new behavior to reconcile the dissonance.

The cognitive dissonance theory, counterintuitively, suggests that our actions can influence our subsequent beliefs and attitudes. As humans, we seek consistency among our attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs. Dissonance, or the state of discomfort, arises when there’s a conflict between these cognitions. This discomfort motivates us to resolve the conflict, either by reducing its importance, adding consonant cognitions, or changing the dissonant cognitions.

Imagine walking into a store and trying on a pair of shoes that caught your eye. They’re slightly more expensive than what you’d usually spend, but they fit perfectly and look great. You decide to buy them. As you leave the store, a small voice in your head questions your purchase, reminding you of your budget. To reconcile this internal conflict, you start to think of all the reasons why this purchase was a good decision: the shoes are of high quality, they’ll last a long time, and they can be worn on multiple occasions. By the time you reach home, you’re convinced that buying the shoes was a wise investment, even if it meant stretching your budget a bit.

Consider a user of a digital fitness app. The app, designed for daily exercises, rewards users with badges for consistent workouts. One week, the user skips several days due to a busy schedule. When they return to the app, a message pops up, “You’ve been doing great! But we noticed you missed a few days. Stay consistent for better results!” Faced with the inconsistency between their goal to stay fit (and use the app daily) and their recent behavior, the user feels a tug of cognitive dissonance. To align their actions with their fitness goals, they might decide to resume their daily exercises, prompted by the app’s subtle reminder of their inconsistency.

The study

One of the most influential studies that shed light on the power of cognitive dissonance was conducted by Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith in 1959. Participants in the study were asked to perform a series of boring tasks. After completing the tasks, some participants were paid a significant amount of money to convince another participant (who was actually a confederate) that the tasks were interesting and enjoyable. Another group was paid a very small amount for the same act of persuasion. Interestingly, when later asked about their genuine feelings towards the tasks, those paid the smaller amount actually reported finding the tasks more enjoyable compared to those paid a larger amount. The underlying reason? Those paid less experienced dissonance between their action (saying the task was fun) and their belief (knowing it was boring). To resolve this dissonance, they altered their beliefs to match their actions.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203-210.

Introduced by Leon Festinger in the late 1950s, cognitive dissonance theory posits that individuals seek consistency among their cognitions. When there’s an inconsistency, it results in a state of dissonance, which is inherently uncomfortable. To alleviate this discomfort, individuals might change their behavior, acquire new information, or downplay the conflicting beliefs. Harnessing this principle in design can influence user behavior and decisions by strategically introducing or highlighting inconsistencies in their current beliefs or actions.

Cognitive Dissonance is grounded in the principle that individuals have an inherent desire to ensure consistency between their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. When a discrepancy arises among these elements, it results in a state of tension or discomfort, pushing individuals to resolve this inconsistency to regain cognitive harmony.

Mental models guide users’ expectations based on their prior experiences. Cognitive dissonance can arise when there’s a mismatch between these models and the actual product design. Aligning designs with users’ mental models can enhance user satisfaction and engagement.

Designing products with Cognitive Dissonance

This principle can be a powerful tool for product designers, offering various ways to enhance user engagement and experience.

- Onboarding and User Engagement

After users invest time in customizing a product or setting up a profile, they’re more likely to engage further to justify their initial investment. Prompting users to make small commitments during onboarding can lead to increased engagement as they seek consistency with their initial decisions. - Highlighting Disconnect

Pointing out the gap between a user’s stated goals and their actual behaviors can motivate change. However, it’s essential to approach this with sensitivity to ensure the user doesn’t feel attacked or overly pressured. - Resolving Dissonance

The presence of cognitive dissonance motivates users to reduce it. Designers can help users by providing reasons that support their product choices, showcasing reviews and testimonials, and highlighting the product’s value. - Engaging in Dialogue

Interpersonal communication can produce cognitive dissonance, breaking down stereotypes and building trust. This can be especially effective in community-driven platforms or products that rely on user collaboration. - Disarming Opposing Behavior

Understanding the opposing side’s expectations and then acting differently can create cognitive dissonance. Consistent behavior that’s visible and can’t be ignored can yield significant results, enhancing user trust and loyalty.

However, designers must be cautious. One major pitfall in applying cognitive dissonance is becoming too aggressive in highlighting discrepancies in user behavior and beliefs. Overemphasis can make users feel judged or cornered, resulting in resistance or even disengagement from the product. It’s also essential to avoid creating dissonance that doesn’t offer a clear path to resolution. If users feel a mismatch between their actions and beliefs but aren’t provided tools or options to reconcile the difference, they might experience unnecessary distress.

Excessive reliance on inducing cognitive dissonance, especially over extended periods, can inadvertently amplify the chasm between users’ self-perceptions and their actual behaviors. Such a persistent tug-of-war can lead to an unintended consequence: a diminished self-esteem. For a user, constantly being reminded of their shortcomings or deviations from ideal behaviors can foster feelings of inadequacy. Over time, this could result in users distancing themselves from the platform altogether. The very tool aimed to engage might become the reason for disengagement.

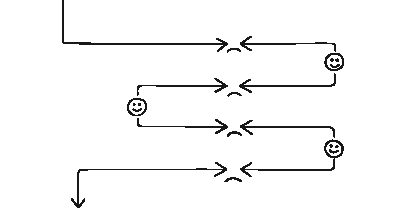

To maximize the benefits and minimize the pitfalls, designers should envision the user experience as a carefully calibrated rollercoaster ride. Like the highs and lows of a coaster, cognitive dissonance should be intermittently introduced, followed by periods of relief and support.

Imagine a health app that regularly reminds users about missed workout sessions. If employed too frequently, these reminders could demotivate users. However, if, after a reminder, the app offers a tailored workout plan, supportive messages, or shares success stories, it provides that necessary relief. Then, once the user has had a chance to realign their actions with their self-perception, the app can reintroduce cognitive dissonance to push them towards their next milestone.

Too much ease and they stagnate; too much challenge and they retreat. Designers must strike the right balance, ensuring users remain motivated but not overwhelmed. It’s about keeping them on track, offering support, and then gently nudging them forward when they’re ready to take the next step.

Any use of cognitive dissonance should be aligned with the genuine benefit of the user, not just business metrics. Ethically leveraging this pattern means prioritizing user well-being and long-term value over short-term gains.

Ethical recommendations

Cognitive dissonance, as a persuasive pattern, has the potential to be misused in ways that can manipulate users into actions that might not be in their best interests. Specifically, companies might exploit this psychological phenomenon to make users feel uncomfortable or inadequate about their current status, pushing them to make purchases or take actions that they wouldn’t have otherwise considered. For instance, a fitness app might overly emphasize a user’s lack of activity, making them feel guilty and pushing them towards buying a premium plan without considering if it genuinely suits their needs.

Moreover, an excessive reliance on inducing cognitive dissonance can lead to users feeling overwhelmed, anxious, or demotivated. If a digital product continuously highlights the gap between a user’s self-perception and their actual behavior, it might result in decreased self-esteem or users disengaging from the platform entirely.

Real life Cognitive Dissonance examples

Nike's "Just Do It"

By promoting an active lifestyle and showcasing athletes of all levels, Nike’s famous slogan creates cognitive dissonance for those leading sedentary lives. This nudge can prompt individuals to buy athletic wear and become more active.

Fitbit

Users who believe they’re active might experience cognitive dissonance when Fitbit reminds them they haven’t met their hourly activity goal. This can motivate users to move more throughout the day.

Apple's Screen Time

Apple’s feature shows users how much time they spend on different apps. This can induce cognitive dissonance in users who believe they don’t use their phones excessively, prompting them to adjust their usage habits.

Trigger Questions

- How does the design align or misalign with users' existing beliefs and behaviors?

- Can we subtly spotlight a gap between users' actions and their stated goals to motivate change?

- How can we provide users with tools or options to resolve any introduced dissonance?

- How can we offer supportive feedback after introducing cognitive dissonance to ensure users don't feel overwhelmed?

- Are we leveraging cognitive dissonance for genuine user benefit or just business metrics?

- How can we ensure the induced cognitive dissonance doesn't adversely impact users' self-esteem or well-being?

Pairings

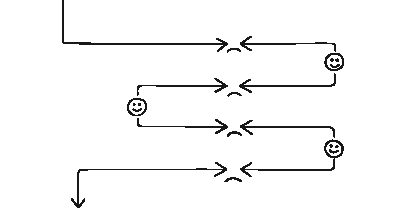

Cognitive Dissonance + Commitment & Consistency

Once a user commits to a certain action or belief, any dissonance experienced can further cement their commitment. For example, if a user publicly pledges to a fitness goal on a health app and later slacks off, the inconsistency between their public commitment and actual behavior can create dissonance. This dissonance might push them to be more consistent with their workouts.

When we do something that is not in line with our beliefs, we change our beliefs

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

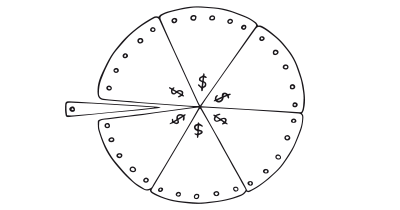

Cognitive Dissonance + Social Proof

Combining the power of seeing others take an action and experiencing dissonance can be potent. For instance, on a learning platform, if users see their peers completing courses and they haven’t, they might feel the dissonance between their self-perception as a keen learner and their current actions.

When we do something that is not in line with our beliefs, we change our beliefs

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

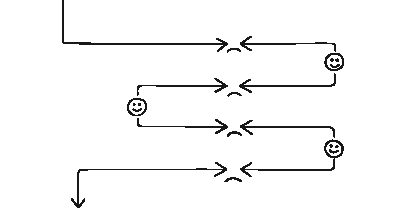

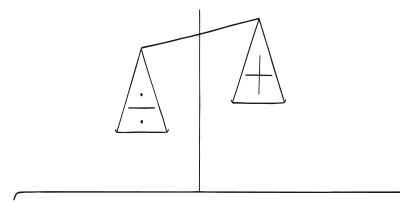

Cognitive Dissonance + Loss Aversion

Loss aversion plays on users’ tendencies to strongly prefer avoiding losses over acquiring gains. Coupled with cognitive dissonance, it can make users take actions to avoid potential loss. An example is a finance app that shows how much money a user could have saved if they had invested earlier. The dissonance between their belief of being financially savvy and the reality of missed opportunities can drive action.

When we do something that is not in line with our beliefs, we change our beliefs

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance by Festinger

- Cognitive Dissonance [ by Harmon-Jonas & Mills

- Cognitive Dissonance: How Contradictory Ideas Affect Design by Steven Bradley at Vanseo Design

- Cognitive Dissonance (Leon Festinger) at InstructionalDesign.org

- Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203-210.

- Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177-181.

- Aronson, E., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1963). Effect of the severity of threat on the devaluation of forbidden behavior. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(6), 584-588.

- Cooper, J., & Fazio, R. H. (1984). A new look at dissonance theory. Advances in experimental social psychology, 17, 229-266.

- Stone, J., Aronson, E., Crain, A. L., Winslow, M. P., & Fried, C. B. (1994). Inducing hypocrisy as a means of encouraging young adults to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(1), 116-128.

- William Lidwell (2003), “Universal Principles of Design”

- Brehm, J. & Cohen, A. (1962). Explorations in Cognitive Dissonance. New York: Wiley.

- Wickland, R. & Brehm, J. (1976). Perspectives on Cognitive Dissonance. NY: Halsted Press.