Persuasive Patterns: Influence

Status-Quo Bias

We prefer the current state instead of comparing actual benefits to actual costs

Status-Quo Bias refers to a cognitive preference for the current state of affairs, where individuals tend to resist change and prefer maintaining their current choices or behaviors.

Imagine a person, Alex, who has been using the same brand of toothpaste for years. One day, while shopping, Alex notices a new brand on sale, boasting advanced benefits and a fresh minty flavor. Despite the potential benefits and the discounted price, Alex feels an inclination to stick with the familiar brand, even if it might not be the best option available. This inclination isn’t necessarily because Alex believes the familiar brand is superior, but rather due to an inherent preference for the current state of affairs or the “status quo”. This tendency to favor the familiar over the new, even when the new might be better, is a manifestation of the status-quo bias.

Consider a user, Jamie, who has been using a particular online cloud storage service for several years. Jamie receives an email about a new cloud service offering more storage space at a lower cost, with better security features. Despite the clear advantages of the new service, Jamie hesitates to make the switch. The process of transferring files, learning a new interface, and the mere thought of change makes the current service seem more appealing, even if it’s not the most efficient or cost-effective option. This digital inertia, favoring the current platform over a potentially better one, is a clear example of the status-quo bias in the realm of digital products.

The study

One of the most influential studies that dove into the intricacies of the status quo bias was conducted by William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser in 1988. Their research examined how individuals often display a preference for the current state of affairs, even when alternative options might be more beneficial. In their experiment, they observed the selections of health plans and retirement programs by faculty members. The findings were striking: the status quo bias was substantial in these important real decisions. In essence, individuals were more inclined to stick with their current choices, even if changing might have been in their best interest. This bias towards the existing state was evident even when the stakes were high, such as in decisions about health and retirement.

B. Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7-59.

The Status-Quo Bias is fundamentally rooted in the principle of Loss Aversion. People generally perceive the pain of losing something as more significant than the pleasure of gaining something of equal value. This makes individuals more likely to maintain their current state to avoid potential losses, even if change might bring about benefits.

The human mind is wired to prefer stability and familiarity. The Status-Quo Bias manifests as an inherent reluctance to alter an existing situation, even if there might be significant benefits in doing so. This bias can be attributed to several factors, including the fear of potential losses that might accompany change, the comfort of the familiar, and the mental effort required to evaluate new options. In product design, understanding this bias can help designers anticipate user behaviors, especially in scenarios where change is introduced, or when users are required to make decisions.

Designing products with the Status-Quo Bias

By setting strategic defaults or presenting familiar options as the norm, designers can subtly guide users towards desired outcomes. This doesn’t mean trapping users in a decision they wouldn’t naturally make, but rather framing choices in ways that resonate with their inherent desire for consistency. It’s essential, though, to always prioritize user benefit and ensure that leveraging this bias doesn’t compromise their best interests.

A significant pitfall when leveraging the Status-Quo Bias is overestimating its power and neglecting genuine user needs. For instance, if a product’s default settings compromise user experience or privacy, relying on users’ tendency to stick with the status quo can backfire. Another common error is failing to communicate clearly when a default option might lead to additional costs or commitments, which can erode trust and damage brand reputation.

Our tendency as humans to favor familiar experiences and previously made decisions is deeply rooted in our cognitive processes. When designing products, understanding and leveraging this bias can yield compelling outcomes. Here are a few specific tips on how to apply this understanding:

- Leverage heuristic shortcuts

Recognizing that humans often depend on heuristic shortcuts, or mental rules of thumb, designers can create interfaces and experiences that align with these intuitive processes. By presenting options in familiar ways or aligning with previous decisions, users can be guided towards desired outcomes. - Present strategic defaults

The complexity of a decision can often deter users from making choices. Hence, by presenting users with strategic default options, you can make decision-making smoother for them. This not only aids in quicker decisions but also steers users towards choices that might be beneficial for the product or service. - Highlighting loss vs. gain

The Status-Quo Bias suggests that once an item or service is acquired, its value is perceived differently. Users are more averse to the idea of losing what they have than the idea of gaining something new (the Endowment Effect). Design strategies can emphasize what users stand to lose if they change their current choices, making them more likely to stick with the status quo. - Using good defaults for ease

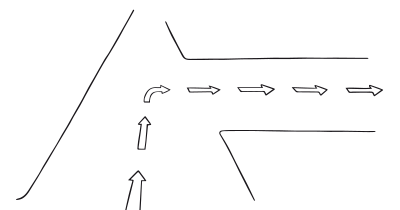

In areas where decisions can be overwhelming, such as forms or selections, employing a ‘Good Defaults’ design pattern can help users make choices. By pre-selecting options based on popular or commonly chosen preferences, the cognitive load on users is reduced, making the process smoother. - Pre-select your wanted response

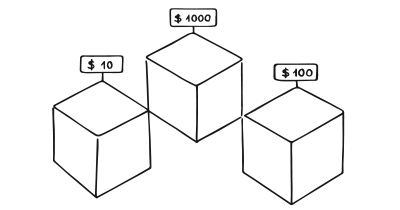

When the user has a number of options to choose from, you can help him or her on the way by framing one of the options as the default option. Understanding and comparing multiple options takes its toll on our cognitive load. - Reframe system changes

If a product undergoes significant changes, consider how you might present this change. Instead of positioning it as a complete overhaul, consider presenting it as an enhancement or alternative. This can reduce resistance and make users more receptive. - Limit choice

More choice is not always better. Having many choices might grab our attention, but too many can overwhelm us to the point where we are likely to not choose (or buy) at all. Complexity delays choice, further increasing the fraction of consumers, who will adopt the default options. - Beat the bias

If you want people to change, show them the cost of staying the same, as well as potential gains. Paint a clear and visual contrast between their current state and desired future state. Consider telling a before-and-after hero story to identify with highlighting challenges relevant to the audience. - Force active decision making

If you want users to make a significant decision, sometimes it’s effective to force the decision upon them. This could be done by ending a free trial, changing subscription plans, or making the current status quo seem less compelling. By doing so, users might re-evaluate their choices and potentially make decisions that align with the desired outcomes.

Ethical recommendations

Our natural inclination towards maintaining the status quo presents ethical challenges that professionals must navigate with care.

One of the most prominent concerns is the potential for manipulating choices. Companies, aware of this bias, might set certain options as defaults, subtly guiding users towards decisions that may not serve their best interests. For instance, pre-checked boxes in online forms, if overlooked, can lead to unwanted subscriptions or additional services. Such tactics, while effective, can erode trust and harm user experiences.

By making alternatives less visible or attractive, businesses can exploit this bias, ensuring that users stay locked into a particular choice, even if better options exist. This can be particularly concerning when the change, like adopting a more secure software version or transitioning to a more environmentally-friendly product, is clearly beneficial.

So, how can businesses ethically leverage the Status-Quo Bias without crossing these boundaries?

- Transparency is key

All options should be presented clearly, and any potential implications of a choice, especially defaults, should be made explicit. Hidden terms, conditions, or pre-selected options can lead to feelings of deception and should be avoided. - Facilitate informed informed decision-making

Instead of banking on users passively accepting defaults, they should be provided with the information and tools to make active, informed choices. This could involve offering detailed comparisons, user reviews, or clear lists of benefits and drawbacks for different options. - Make reversal easy

If a user does inadvertently opt for a default choice, they should find it easy to reverse that decision, especially if it involves subscriptions or long-term commitments. Locking users into choices, especially unintentional ones, can be detrimental to trust and brand reputation. - Educate users

Rather than relying on the Status-Quo Bias alone, businesses should actively highlight the benefits of new features, services, or products. By emphasizing the advantages of change and providing value, users can be encouraged to make decisions that align more closely with their interests.

Real life Status-Quo Bias examples

E-commerce Platforms

Many online shopping platforms highlight products that are “Doctor Recommended” or “Certified Organic” to assure customers of the product’s quality and safety.

Financial Tools

Investment platforms and apps often showcase advice or recommendations from reputed financial experts or analysts, enhancing user confidence in the platform’s offerings.

Educational Websites

Online courses or learning platforms may highlight their affiliation with top universities or feature endorsements from industry leaders to appeal to learners.

Trigger Questions

- How can we set our product's default options to align with common user preferences?

- In what areas might users benefit from a nudge towards maintaining their current choice?

- Are there processes or decisions where introducing a change might disrupt users' sense of continuity?

- How can we ensure that leveraging the Status-Quo Bias doesn't compromise user autonomy or well-being?

- Are there any ethical implications in the default choices we're presenting to our users?

- How might we test the impact of different defaults on user satisfaction and decision-making?

Pairings

Status-Quo Bias + Social Proof

Combining the Status-Quo Bias with Social Proof can create a compelling narrative for users. For instance, if a software application maintains a default setting (Status-Quo Bias) and simultaneously highlights that “90% of users prefer this setting” (Social Proof), it reinforces the user’s inclination to stick with that choice.

We prefer the current state instead of comparing actual benefits to actual costs

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

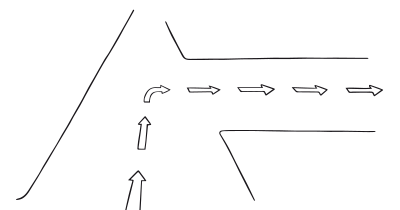

Status-Quo Bias + Anchoring Bias

Users often rely on the first piece of information (the “anchor”) when making decisions. If the status quo is presented as this anchor, it can guide subsequent decisions in its favor.

We prefer the current state instead of comparing actual benefits to actual costs

We tend to rely too heavily on the first information presented

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Status quo bias in decision making by Samuelson & Zeckhauser

- Anomalies: Endowment Effect by Kahneman, et. al.

- Episode 11: Status Quo Bias

- Why Change: Defeating Status Quo Bias by | Devon Hennig at Devon Hennig

- Episode 11: Status Quo Bias

- How the Status Quo Bias Affects Our Decisions at Verywell Mind

- Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7-59.

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193-206.

- Halpern, S. D., Ubel, P. A., & Asch, D. A. (2007). Harnessing the power of default

- Dean, M., Kıbrıs, Ö., & Masatlioglu, Y. (2014). Limited Attention and Status Quo Bias. ERN: Experimental Economics (Topic).

- Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1992). Status-quo and omission biases. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 49-61.

- Schweitzer, M. (1995). Multiple reference points, framing, and the status quo bias in health care financing decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 63, 69-72.

- Krieger, M. A., & Felder, S. (2013). Can Decision Biases Improve Insurance Outcomes? An Experiment on Status Quo Bias in Health Insurance Choice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 2560-2577.

- Moshinsky, A., & Bar-Hillel, M. (2010). Loss Aversion and Status-Quo Label Bias. Social Cognition, 28, 191-204.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341.

- Anderson, J. R. (1990). Cognitive psychology and its implications. WH Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

- O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2004). Incentives and Self-Control. In C. F. Camerer, G. Loewenstein, & M. Rabin (Eds.), Advances in Behavioral Economics (pp. 90-122). Princeton University Press.

- Johnson, E. J., Hershey, J., Meszaros, J., & Kunreuther, H. (1993). Framing, probability distortions, and insurance decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 7(1), 35-51.

- Weinschenk, S. M. (2009). Neuro Web Design: What makes them click? New Riders.