Persuasive Patterns: Restructuring, Obligation

Default Effect

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

The default effect describes our tendency to favor pre-selected choices. When presented with options, we are more likely to choose the one that is already selected for us.

You might experience a sense of decision fatigue as you traverse a supermarket cereal aisle and you’re faced with a seemingly endless wall of brightly colored boxes. Do you choose the familiar brand you always buy, explore a healthier option, or succumb to the lure of a cartoon character on a brightly colored box? Interestingly, research by Iyengar and Lepper (2000) suggests that the store’s placement of a pre-selected “featured” cereal can influence your choice. Even if you don’t ultimately select the featured option, it serves as a starting point, subtly Priming your decision-making process.

This nudge towards pre-selected options can also be seen in digital products. Many streaming services, for instance, offer a “default” subscription plan during sign-up. This plan, often highlighted or pre-selected, represents the service’s preferred choice, perhaps the most popular option or one that aligns with the user’s browsing history. Research by Schwartz et al. (2007) highlights the power of this default effect. Users presented with a pre-selected plan are more likely to choose it, even if other, potentially more suitable options are available. This demonstrates how digital products leverage the default effect to streamline user decisions and potentially increase sign-ups for their preferred subscription tiers.

The study

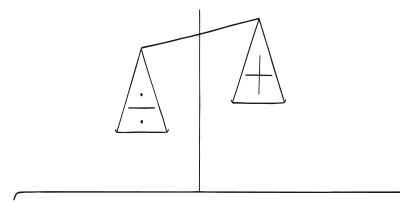

The seminal study “Do Defaults Save Lives?” by Johnson and Goldstein (2003) investigates how the Default Effect influences organ donation rates in various countries. The study compared organ donation rates in nations with opt-in policies (where individuals must actively choose to become organ donors) versus countries with opt-out policies (where individuals are automatically enrolled as donors unless they choose to opt out).

The study found that countries with opt-out policies, such as Austria and Belgium, had organ donation rates exceeding 90%, compared to rates as low as 15% in countries with opt-in policies like Denmark and Germany. This significant difference demonstrates the Default Effect’s power to shape behavior, even in crucial decisions such as organ donation.

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338-1339.

This pattern leverages the human inclination to avoid making decisions that require significant mental effort. In a world where people are constantly bombarded with choices, default options simplify the decision-making process. By setting a specific choice as the default, designers can guide users towards desired behaviors or outcomes, minimizing decision fatigue and increasing the likelihood of conversion.

The Default Effect, though not explicitly named until the late 20th century, has roots in various schools of thought dating back to the early 1900s. Early behavioral economics experiments by psychologists like Shepard (1964) explored the concept of reference points, laying the groundwork for understanding how pre-selected options can influence choices.

The Default Effect is a powerful force shaping our decisions. It revolves around the tendency to favor pre-selected options, even if alternatives might be objectively better. This phenomenon is rooted in several core principles of human psychology and cognitive biases.

One key concept is Status-Quo Bias, a natural human preference to maintain the current state and avoid the effort of change (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Defaults become the initial reference point, requiring less mental effort than actively evaluating and selecting another option. Studies by Johnson and Goldstein (2003) on organ donation rates exemplify this. They found that opting-in to be a donor, the default option, led to significantly higher registration rates compared to an opt-out system. People were more likely to stick with the pre-selected choice, highlighting the power of the status quo bias.

This preference for the status quo is further amplified by our tendency to conserve cognitive resources, aligning with the concept of cognitive miser theory. Defaults act as a mental shortcut (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). Imagine you’re finally setting up your dream vacation to Hawaii. Faced with dozens of hotel options, each with various room types, meal plans, and activity packages, you start to feel overwhelmed. Analysis Paralysis sets in! This is where defaults can be a lifesaver. Many booking platforms offer pre-selected options based on popular choices or your past preferences. These defaults act as a starting point, reducing the mental effort required to make a decision (Madrian & Shea, 2001). With the default as a foundation, you can customize your trip with greater ease, focusing on the details that matter most to you.

Loss Aversion, another key factor at play, refers to the tendency for people to fear potential losses more than they value potential gains (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). A pre-selected option feels like the “safe” choice, avoiding the risk of making a suboptimal decision by actively selecting something else. This can be particularly helpful when faced with complex choices or decision fatigue, as defaults offer a way to avoid the potential regret of a bad decision.

The Anchoring Bias is another factor influencing the Default Effect. Our initial impressions heavily influence subsequent judgments. A pre-selected option serves as an anchor, subtly influencing our evaluation of other options relative to it (Schwartz et al., 2007). This can be seen in subscription services that often highlight a default plan. While other plans might exist, the initial focus on the pre-selected option, the anchor, shapes our perception of value for the other options.

However, defaults can be a double-edged sword. While they can simplify decision-making, they can also be misused to nudge users towards choices that benefit the company more than the user. This can trigger a phenomenon called “reactance,” where people feel a loss of control and rebel against the default by choosing the opposite option (text provided). For example, a pre-checked box for a paid service during checkout might backfire if users feel pressured into it.

The Default Effect is a powerful tool that can be used to create a smoother decision-making process for users, ultimately guiding them towards better outcomes. By designing defaults with user needs in mind, we can ensure they act as helpful guides rather than manipulative nudges.

Designing products with the Default Effect

Defaults can simplify user decision-making, guide users towards desired actions, and ultimately improve the user experience. Let’s explore how to leverage the Default Effect effectively, considering the psychology behind it and incorporating practical tips for implementation.

Defaults offer several benefits. They reduce the cognitive load associated with decision-making, acting as mental shortcuts that free up mental resources for users. Defaults can also nudge users towards desired actions, subtly influencing their choices without feeling manipulative. Furthermore, well-chosen defaults can establish a reference point (anchoring bias), shaping how users evaluate other options presented.

Mass Defaults vs Personalization Defaults

Defaults can be broadly categorized into two types: Mass Defaults and Personalized Defaults.

- Mass Defaults

These are one-size-fits-all options applied uniformly to all users. Examples include pre-selecting “standard shipping” on an e-commerce platform or offering a “high quality” audio option on a music streaming service. The goal is to choose a default that aligns with the needs and preferences of the majority of users. - Personalized Defaults

These defaults take user data or past behavior into account, offering a more tailored experience. For instance, a news app might pre-select preferred news sources based on a user’s browsing history, or a fitness tracker app might suggest a daily step goal based on the user’s activity level. Personalized defaults can increase user satisfaction and engagement by catering to individual needs.

The foundation lies in choosing defaults that resonate with your target audience. Consider typical user needs, preferences, and even experience level. For instance, a complex tax filing software might pre-select a “step-by-step guided filing” option for beginners, while offering a “customizable filing” option for experienced users. This caters to different user comfort levels and simplifies the process for each group.

Defaults can subtly nudge users towards specific choices. In e-commerce, pre-selecting standard shipping over expedited shipping reduces the perceived risk of exploring alternative options. This creates a smoother and more intuitive buying experience, while potentially increasing the likelihood of users sticking with the default (standard shipping) if they aren’t in a rush.

Offering too many options can lead to Analysis Paralysis. Simplify the decision-making process by limiting options initially. For instance, a music streaming service might pre-select “high quality” audio as the default, assuming most users prioritize sound fidelity. This streamlines the process while aligning with user expectations. However, consider offering a clear and easily accessible option for users who prefer a lower quality stream to save on data usage. This empowers users and avoids the perception of being forced into a single choice.

Design can create a clear decision path (Tunneling), leading users through a sequence of choices with a pre-selected option at the start. This approach guides users towards a specific outcome while minimizing the need to evaluate multiple options simultaneously. Onboarding processes can leverage this strategy by introducing pre-selected privacy settings to streamline initial setup. Be transparent about the rationale behind your defaults. Briefly explain why the pre-selected option is beneficial and how it aligns with user needs. This transparency fosters trust and encourages users to opt-out if desired, while also giving them the confidence to explore alternative options.

Tailoring matters

While “Mass Defaults” offer a one-size-fits-all approach, consider “Personalized Defaults” for a more user-centric experience. Leverage customer data (when appropriate) to suggest optimal choices. Defaults can be persistent, remembering historical user choices (e.g., pre-selecting preferred news sources on a news app), or adaptive, updating based on real-time user interactions (e.g., recommending similar products based on past purchases on an e-commerce platform).

Remember:

- Pre-select wisely

Choose defaults that align with common user goals or established best practices. Consider the context: a fitness tracker app might pre-select a daily step goal based on health guidelines, while a news app might pre-select a “headlines only” view for users seeking quick updates. - Offer clear opt-out options

Empower users with control. Provide clear and easy ways for users to opt-out and explore alternative options. Don’t bury these options in labyrinthine menus.

Also consider:

- Pre-populate forms

In forms, pre-populate fields with the most common value if predictable (e.g., country field based on user IP address). This saves users time and effort. - Educate and guide

Default values should be helpful, not arbitrary. Choose defaults that educate and guide users.

Ethical recommendations

The Default Effect can easily be used unethically or to the detriment of users. One main risk is that companies might set defaults that prioritize their own interests over those of their users. For example, pre-selecting more expensive options or auto-renewing subscriptions can lead users into decisions that don’t align with their needs. Additionally, presenting defaults that conceal important information or steer users away from better alternatives can undermine trust and lead to long-term dissatisfaction.

Another ethical concern is that defaults can reinforce behavioral inertia, trapping users in suboptimal choices. This is particularly harmful when users are not fully aware of the defaults’ implications, leading to unintended financial or personal consequences. For instance, defaulting individuals into long-term contracts without highlighting the opt-out option can lead to significant costs over time.

- Hidden defaults

Pre-selecting options without clear disclosure can be deceptive. Users might unknowingly accept defaults that incur hidden costs or restrict functionality. Transparency is key. - Exploiting Loss Aversion

Defaults can exploit our natural aversion to losses. For instance, pre-selecting a paid subscription with a free trial might pressure users to take action to avoid losing the perceived benefit, even if they don’t intend to pay after the trial period. Defaults should be beneficial, not a source of anxiety. - Nudging towards unhealthy choices

Defaults can be used to nudge users towards choices that aren’t in their best interest. Imagine a social media platform pre-selecting endless scrolling as the default news feed view. This can contribute to excessive screen time and hinder mindful consumption of content. Defaults should promote healthy user behavior. - Reduced user autonomy

Over-relying on defaults can reduce user autonomy and the sense of control. Users should always have clear and easy ways to opt out of pre-selected options and explore alternatives.

To ensure the Default Effect is used ethically and in a user-centric manner, designers should prioritize transparency and user empowerment. Clearly communicate the rationale behind the default, highlighting both its benefits and potential drawbacks. Recommendations are:

- Be transparent

Be upfront about why certain options are pre-selected. Explain the rationale behind the defaults and how they benefit users. - Provide clear opt-out options

Don’t bury opt-out mechanisms in complex menus. Make it easy for users to choose a different option if the default doesn’t suit their needs. - Align defaults with user needs

Defaults should be user-centric, not solely focused on business goals. Consider typical user behavior and preferences when choosing defaults. - Prioritize user control

The goal is to guide users, not manipulate them. Defaults should empower users to make informed choices and feel in control of their experience.

Real life Default Effect examples

MyFitnessPal

This nutrition tracking app offers default calorie goals based on user profiles, guiding users toward healthy eating habits. The app also allows users to set default meal times and track food intake consistently, helping them maintain a balanced diet.

Web Browsers

Internet browsers such as Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox often set default search engines, homepages, and toolbars, enhancing the overall browsing experience. This helps users quickly navigate the internet without manually setting up these options, streamlining functionality.

Adobe

Adobe’s Creative Cloud subscription defaults to an annual plan, with an option to opt for a monthly plan. This default option nudges users towards a longer-term commitment, providing Adobe with stable revenue streams while reducing cognitive load on users by offering a straightforward choice.

Trigger Questions

- Which decisions create the most friction or require significant user effort?

- Are we setting defaults that simplify decision-making and reduce cognitive load?

- How can we personalize defaults based on user behavior or preferences?

- Can we leverage decoy options to subtly increase the perceived value of the default?

- How can we frame the default option to emphasize its benefits and encourage user acceptance?

- Can a well-chosen default simplify these decisions without sacrificing user control?

- Does the default option align with established best practices or user expectations?

- How can we provide clear and easy ways for users to opt out of the default if needed?

- How can we be transparent about the rationale behind our default selections?

Pairings

Default Effect + Limited Choice + Analysis Paralysis

Offering fewer options reduces decision fatigue. This combines well with the Default Effect. A video streaming service might pre-select a “curated playlist” option alongside a limited selection of popular categories. This simplifies the user experience and encourages exploration within the pre-selected content.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

Default Effect + Commitment & Consistency

The Default Effect can work alongside Commitment & Consistency by offering pre-selected options that align with users’ prior behaviors or stated goals. For instance, a subscription-based service can set a default renewal plan that reflects the user’s initial choice, encouraging consistency over time.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

Default Effect + Social Proof

Defaults can leverage Social Proof by pre-selecting options that align with popular choices among a broader user base. For example, an e-commerce platform might default to “most popular” products or configurations, reinforcing the user’s decision by showcasing what others have chosen.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

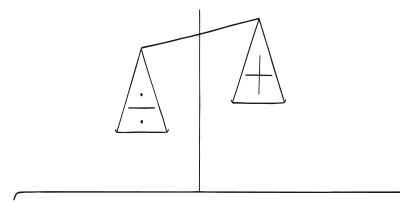

Default Effect + Loss Aversion

The Default Effect’s potential to mitigate loss aversion can be enhanced by highlighting the potential gains or losses associated with choosing or discarding the pre-selected option. For instance, a service might emphasize the benefits lost if a user opts out of the default choice, reinforcing the tendency to stick with it.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Default Effect + Limited Choice

The Default Effect reduces the cognitive load associated with decision-making, much like Limited Choice. By offering a limited selection of pre-determined options, designers can guide users more effectively, minimizing analysis paralysis and encouraging quicker decisions.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

Default Effect + Anchoring Bias

The Default Effect can work in tandem with Anchoring Bias, which influences how subsequent decisions are framed relative to the initial option. By presenting a default choice as an anchor, designers can influence how users perceive and evaluate other options, guiding them toward a particular decision.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We tend to rely too heavily on the first information presented

Default Effect + Authority Bias + Halo Effect

Leveraging the perceived authority of a trusted figure or brand can strengthen the influence of a default setting. For example, a fitness app might pre-select a daily step goal endorsed by a renowned health professional, increasing user acceptance of the default.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We have a strong tendency to comply with authority figures

We let impressions created in one area influence opinions in another area

Default Effect + Loss Aversion

Playing on our natural aversion to losses can make opting out of a pre-selected option feel less appealing. Imagine a news subscription service that defaults to a “yearly plan” with a significant discount compared to the monthly option. Users might be more likely to stick with the default to avoid losing the perceived value of the discount.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Default Effect + Endowment Effect

The Default Effect pairs well with the Endowment Effect, where individuals value an option more simply because they possess it. By setting a default choice, users may feel a sense of ownership over the pre-selected option, increasing its perceived value. This can work effectively in product customization interfaces, where default configurations encourage users to maintain their initial selections.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We value objects more once we feel we own them

Default Effect + Priming Effect

The Default Effect can pair with the Priming Effect to set the stage for future decisions. By pre-selecting an option that is also chosen and committed to, designers can prime users to think along specific lines, making them more receptive to subsequent nudges or choices. For example, in a software onboarding flow, default settings can set a baseline, influencing how users approach later configuration steps.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

Decisions are unconsciously shaped by what we have recently experienced

Default Effect + Anchoring Bias

The Default Effect works hand in hand with Anchoring Bias, which influences how users assess subsequent options. By establishing a default choice as an anchor, users are more likely to compare other options to it, shaping their evaluations and guiding them toward decisions consistent with the initial default.

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

We tend to rely too heavily on the first information presented

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you build lasting habits, facilitate behavioral commitment, build lasting habits, and understand the human mind. It is presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Nudge: Improving decisions about health by Thaler & Sunstein

- Do defaults save lives? Science by Johnson & Goldstein

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

- Schwartz, B., Randall, D. T., Ginzburg, M., & Ksimian, R. J. (2007). Choice and framing effects in risky decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 35(3), 223-238.

- Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338-1339.

- Madrian, B. C., & Shea, D. F. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4), 1149-1187.

- Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. G. (2003). Do defaults save lives? The effect of biometric registration defaults on organ donation rates. Journal of Public Economics, 87(3-4), 147-174.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- Asch, S. E. (1951). Opinions and social pressure. Psychological Monographs, 65(9, Whole No. 331).

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Shepard, R. N. (1964). On subjectively optimal sequences. Psychological Review, 71(3), 230-243.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.