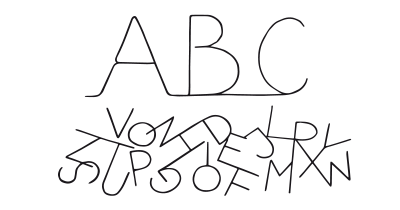

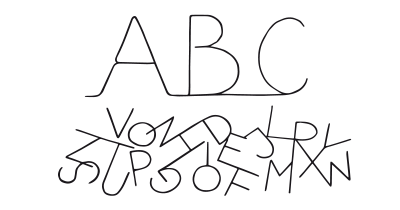

Persuasive Patterns: Education

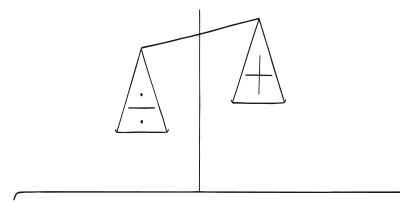

Analysis Paralysis

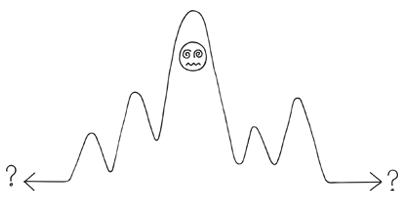

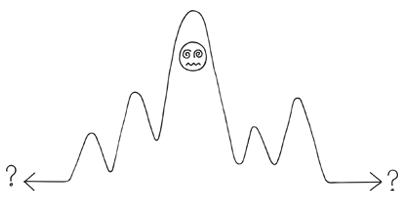

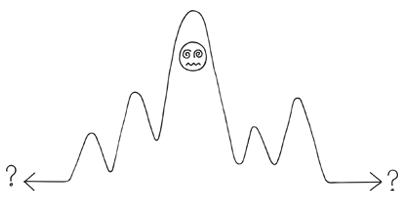

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

Analysis Paralysis is a psychological pattern in which individuals feel overwhelmed by the number of available choices, leading to difficulty in making a decision or taking action.

Analysis Paralysis can creep into our everyday lives in surprising ways. Imagine standing in a grocery store aisle overwhelmed by the sheer number of bottled water brands, each touting its unique selling proposition (e.g., sourced from glaciers, infused with electrolytes). The desire to make the “perfect” choice, coupled with the multitude of options, can lead to decision fatigue and ultimately, inaction. You might resort to grabbing a familiar brand or simply postponing the decision altogether.

This tendency to overthink translates seamlessly into the digital world. Consider the process of choosing a new streaming service. Presented with a plethora of options, each with varying subscription tiers, content libraries, and interface designs, users might find themselves paralyzed by indecision. The fear of missing out on the “best” option or the complexity of comparing features can lead to endless research and analysis, ultimately delaying the decision to sign up for any service (Singh & Tripathi, 2019).

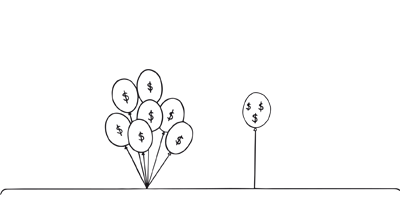

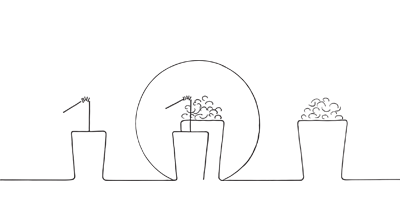

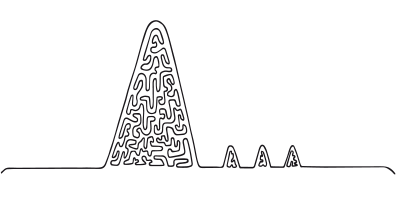

The study: Too much jam

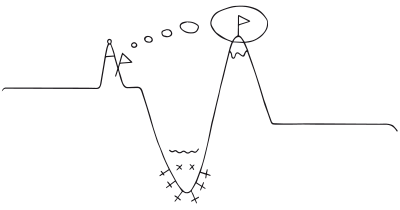

A seminal study on Analysis Paralysis was conducted by Iyengar and Lepper in 2000. The study investigated the impact of choice overload on decision-making behavior. They set up a supermarket display featuring either 6 or 24 varieties of jams. Customers lingered significantly longer browsing the wider selection (24 jams). However, a surprising twist emerged: those presented with 6 jams were far more likely to make a purchase (31%) compared to those overwhelmed by 24 choices (only 3% ended up buying jam). This research highlights the paradox of choice: an abundance of options can lead to Analysis Paralysis, hindering decisions and reducing satisfaction.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

Analysis Paralysis arises from the human tendency to overanalyze information when faced with multiple options, leading to indecision and stagnation. This pattern can hinder progress in various areas, from completing tasks to making consumer choices. The primary goal of addressing Analysis Paralysis in product design is to simplify decision-making processes, reduce choice overload, and guide users towards desired outcomes. This can lead to improved user experiences, increased conversions, and greater customer satisfaction.

The pattern of Analysis Paralysis is grounded in cognitive psychology and behavioral economics. The main psychological principle underpinning this pattern is the concept of choice overload, where an abundance of options leads to decision fatigue and indecision.

- Choice overload

Cognitive psychology suggests that individuals have a limited capacity for processing information. When presented with numerous options, this capacity can be overwhelmed, resulting in difficulty making a decision. This is because each option requires cognitive resources to evaluate, compare, and make an informed choice. This can lead to an increase in cognitive load, making decision-making more challenging. - Satisficing vs. maximizing

Behavioral economics introduces the concepts of satisficing and maximizing. Satisficers aim to choose an option that meets their basic criteria, while maximizers strive to make the best possible choice. In an environment with many choices, maximizers may feel compelled to evaluate all options thoroughly, which can lead to Analysis Paralysis as they seek the optimal decision. This is exacerbated by the fear of making a suboptimal choice, which can cause further hesitation. - Prospect theory

Prospect theory also plays a role in Analysis Paralysis. This theory suggests that individuals weigh potential losses more heavily than gains when making decisions. Thus, in the context of Analysis Paralysis, the fear of making a wrong choice and experiencing potential losses can lead to decision avoidance, as individuals prefer to maintain the status quo rather than risk making a poor decision. - Regret and anticipation

Underlying Analysis Paralysis is also the fear of potential regret. Decision theory and behavioral economics suggest that people fear making a decision that they might later regret. When faced with numerous choices, individuals anticipate the regret they might feel if they make the wrong choice, leading them to defer making a decision altogether. - Optimization pressure

In modern society, there is often pressure to make the best or most optimized decision, not just a satisfactory one. This maximization tendency can lead individuals to obsess over finding the perfect choice among many, rather than settling for one that meets their needs. - Contrast and comparison

Psychological research shows that humans have a natural tendency to compare available options in order to make decisions. However, excessive comparisons can make each option’s drawbacks more prominent, leading to indecision.

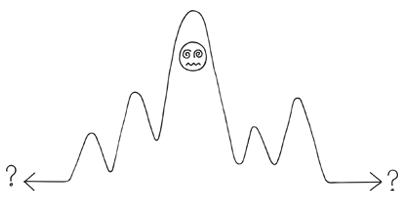

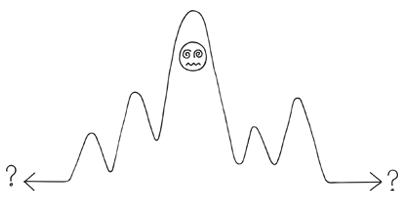

Analysis Paralysis can be explained through Daniel Kahneman’s Dual-Process Theory, which delineates two modes of thinking: System 1 and System 2.

- System 1

This system is fast, intuitive, and automatic. It’s the gut reaction or instinctual response that individuals have when making quick decisions. For example, when shopping, a person might automatically pick a product they’ve purchased before or one that catches their eye. - System 2

This system is slower, deliberate, and analytical. It engages in thorough reasoning and careful evaluation, often weighing the pros and cons before making a choice. In the context of a purchase decision, System 2 might compare products’ features, reviews, and prices to make an informed choice.

Analysis Paralysis often occurs when System 2 is over-engaged. When users face an abundance of choices, their analytical thinking kicks in, causing them to evaluate each option meticulously. This exhaustive comparison process can lead to indecision, as users become overwhelmed by the cognitive load of processing too much information, resulting in a paralysis of action.

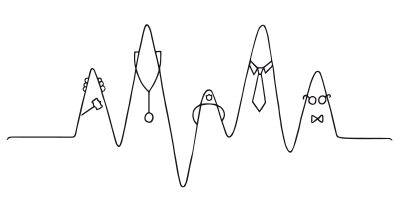

Cognitive Load Theory

Another framework that explains the occurrence of Analysis Paralysis is Cognitive Load Theory, which divides cognitive load into three categories:

- Intrinsic load. This refers to the inherent difficulty of the task or information being processed. Complex decisions with numerous variables can create a high intrinsic load, making it challenging to process and evaluate all factors.

- Extraneous load. This load arises from unnecessary information or distractions that do not contribute directly to the task at hand. For example, a cluttered interface or irrelevant details can increase extraneous load, further complicating decision-making and contributing to Analysis Paralysis.

- Germane load. This is the load associated with structuring and integrating information into existing knowledge, leading to meaningful learning. Germane load is beneficial in moderation, as it helps users build a deeper understanding of their choices. However, excessive germane load can add to the overall cognitive burden, exacerbating Analysis Paralysis.

As a designer, you can alleviate Analysis Paralysis by managing these types of cognitive load:

- Reduce intrinsic load. Simplifying tasks by breaking them down into manageable steps or reducing the number of variables to consider can lower intrinsic load.

- Minimize extraneous load. Streamlining interfaces, eliminating distractions, and presenting only relevant information can reduce extraneous load.

- Moderate germane load. Providing clear structures, summaries, or guides to integrate new information into users’ existing knowledge can enhance germane load without overwhelming the user.

Designing products about Analysis Paralysis

Analysis Paralysis can significantly impact a user’s decision-making process, making it essential to design products that minimize its effects.

When users experience Analysis Paralysis, it can lead to several adverse effects:

- Increased risk aversion

Users may stick to what they know, avoiding new or unfamiliar options, even if they offer better outcomes. - Reduced generosity

The stress and cognitive load associated with decision-making can make users less generous, limiting their willingness to contribute or donate. - Unhealthy choices

Analysis Paralysis can lead to impulsive or unhealthy decisions, such as choosing convenient fast food over a healthier option. - Lack of patience and creativity

Decision fatigue reduces users’ patience and creativity, making them less willing to explore new solutions or innovative approaches. - Loss of focus

The cognitive overload from too many options can inhibit System 2 thinking, making it harder for users to focus, plan, and maintain control.

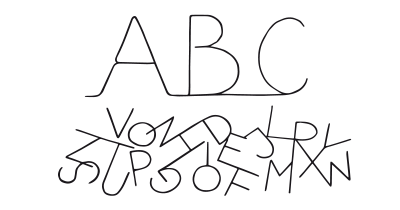

Here are key strategies to design while taking our tendency for Analysis Paralysis into account:

- Limit choices

Reduce the number of available options to streamline decision-making. For instance, e-commerce platforms can simplify product categories, offering a curated selection based on user preferences or past purchases. This narrowing of choices helps users make decisions more easily, minimizing cognitive overload. - Guide users with good defaults

Defaults (Default Effect) are a powerful tool to steer users toward specific choices. In subscription-based services, offering a pre-selected plan that meets typical user needs minimizes the time spent evaluating options. This not only simplifies decision-making but also reassures users that their choice is appropriate. - Implement progressive disclosure

Introduce information gradually, rather than overwhelming users with all the details upfront. In software design, present core features first, allowing users to explore advanced functionalities as needed. This progressive approach maintains focus, reducing the likelihood of Analysis Paralysis. - Utilize visual hierarchies

Clearly distinguish between primary and secondary options through design elements like size, color, and placement. This directs users’ attention to the most relevant choices, simplifying comparisons and decisions. In a mobile app interface, emphasize key actions through bold icons or buttons, relegating secondary actions to smaller, less prominent links. - Provide clear comparisons

For complex products or services, offer straightforward comparison tools to aid decision-making. For instance, a comparison chart highlighting differences between subscription plans or product models can clarify options, helping users quickly identify the best fit for their needs. - Offer decision support

Enhance the decision-making process with features that guide users towards a choice. This might include recommending products based on past behavior or introducing interactive quizzes to match users with the right service. These tools streamline decision-making, reducing the cognitive load associated with evaluating numerous options.

Ethical recommendations

While Analysis Paralysis offers valuable tools for guiding user choices, it’s crucial to acknowledge its potential for misuse. Unethical applications can manipulate users and prioritize short-term gain over long-term user satisfaction.

Limited choices can become a deceptive tactic if they obscure less desirable options or fail to disclose all relevant information, like hidden fees or limitations.

Incessant use of scarcity tactics like “limited-time offers” can create a perpetual sense of urgency, pressuring users into rushed decisions they might later regret.

Decision support features, when biased or misleading, can nudge users towards options that benefit the designer or platform more than the user’s actual needs.

These unethical applications erode trust and can backfire, leading to user frustration and abandonment.

- Provide clarity and disclosure

Present all relevant information about each option, including potential drawbacks and limitations. Avoid obfuscating less favorable choices or burying crucial details. - Provide meaningful defaults

Default selections should be genuinely valuable options, not simply attempts to manipulate user behavior. - Be transparent

Be upfront about the persuasive techniques used. Acknowledge the purpose of limited choices or scarcity tactics, and ensure they are employed ethically.

Real life Analysis Paralysis examples

The search engine giant reduces decision fatigue in its core search product by limiting the number of results shown per page and providing tools such as “People also ask” and “Related searches” to guide users. The autocomplete feature also helps streamline the process by suggesting potential queries as users type.

Netflix

The streaming service tackles Analysis Paralysis by curating a list of recommended content based on user preferences and viewing history. Additionally, features like “Top 10 in Your Country” and “Trending Now” reduce decision fatigue by providing easily accessible options.

Amazon

The e-commerce giant leverages a recommendation engine to present users with product suggestions based on past purchases and browsing history. Furthermore, Amazon’s comparison tools help users quickly evaluate products, minimizing cognitive overload.

Trigger Questions

- Are we limiting the initial choices to the most relevant options?

- Do we clearly highlight the key features and benefits of each option?

- Can we simplify complex processes or information through visuals or step-by-step guides?

- Does our design utilize visual cues to guide users' attention towards the most important choices?

- Are we offering comparison tools to facilitate informed decision-making?

- Do we provide default selections or guidance to nudge users gently in the right direction?

- Do we offer progressive disclosure, introducing additional options gradually?

Pairings

Analysis Paralysis + Social Proof + Limited Choice

Combine curated options (limited choice) with social proof elements like user reviews or testimonials. Imagine a travel booking platform showcasing a limited selection of highly-rated hotels (limited choice), bolstered by positive reviews from previous guests (social proof). This approach leverages the power of social influence to mitigate the burden of choice.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

Analysis Paralysis + Scarcity Bias + Framing Effect

Scarcity tactics like limited-time offers can be effective, but use them ethically. Combine scarcity with positive framing. For instance, a fitness app might highlight a limited-time discount (scarcity) framed as an opportunity to “jumpstart your fitness journey” (positive framing). This approach creates a sense of urgency without overwhelming users with endless options.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

We value something more when it is in short supply

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

Analysis Paralysis + Loss Aversion + Default Effect

People tend to dislike losing more than they enjoy gaining. Combine limited choices with a clearly highlighted default option. For example, a financial services provider might offer a pre-selected investment plan (default) alongside a limited selection of alternative options. Loss aversion can nudge users towards the default choice, simplifying the decision while still offering some control.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

We are more likely to choose a pre-selected option

Analysis Paralysis + Authority Bias

People are often influenced by authority figures. Combine limited choices with decision support tools like expert recommendations or endorsements. Imagine a health insurance platform offering a curated selection of plans (limited choice) alongside recommendations from a team of healthcare professionals (authority bias). This approach leverages the credibility of experts to guide users towards informed decisions.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

We have a strong tendency to comply with authority figures

Analysis Paralysis + Reciprocity

People feel obligated to return favors. Combine limited choices with a free trial period. An e-learning platform might offer a limited selection of premium courses (limited choice) with a free trial period (reciprocity). This allows users to experience the value proposition before committing, reducing the risk associated with choosing the wrong option.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

We feel obliged to give when we receive

Analysis Paralysis + Framing Effect + Limited Choice + Sequencing

The way information is presented can influence our decisions. Pair limited choices with a step-by-step onboarding process framed as a journey of discovery. A new productivity app might present users with a limited set of core functionalities to explore initially (limited choice), followed by a step-by-step onboarding process framed as “unlocking your productivity potential” (framing). This approach breaks down the learning curve and motivates users to engage with the core features before introducing advanced options.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

Analysis Paralysis + Limited Choice + Optimism Bias

People tend to be overly optimistic about future outcomes. Combine limited choices with progress visualization tools. A language learning app might offer a limited selection of learning paths (limited choice) but gamify the process with progress bars and badges (optimism bias). This approach capitalizes on users’ optimism to keep them motivated and engaged in the learning process.

Overwhelmed by choices, we struggle to make a decision

We are more likely to make a decision with fewer options to choose from

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- When choice is demotivating [ by Iyengar & Lepper

- The paradox of choice: Why more is less by Schwartz

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

- Iyengar, S. S., & Kamenica, E. (2010). Choice overload and simplicity seeking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(3), 373-383.

- Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2004). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1178-1197.

- Chernev, A., Böckenholt, U., & Goodman, J. (2015). Choice overload: A conceptual review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 333-358.

- Sheena, Iyengar, S., & Kamenica, E. (2006). Choice architecture: Revealed preference studies of best versus better marketing messages. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 170-178.

- Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. New York: Ecco.

- Guλιάς, M., & Kakarík, M. (2017). Analysis paralysis or information overload? Exploring the impact of online reviews on hotel booking decisions. Journal of Travel Research, 56(2), 226-238.

- Shepard, R. N. (1964). Attention and the differentiation of cognitive sets. Psychological Review, 71(1), 59.