Persuasive Patterns: Demonstration, Facilitation

Sequencing

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

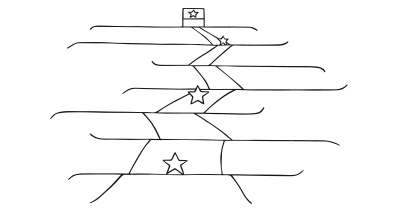

Sequencing is the technique of breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable actions to facilitate task completion.

Imagine you’re assembling a piece of furniture. The instruction manual breaks down the assembly process into small, numbered steps, each with a clear diagram and a list of required parts. You find it easier to focus on one step at a time, completing each one before moving on to the next. This sequencing of tasks helps you maintain your concentration and reduces the cognitive load, making the assembly process smoother and more efficient.

Similarly, imagine you’re using an app that helps you manage your finances. The app doesn’t overwhelm you with all the features at once. Instead, it guides you through a series of steps: first, linking your bank account, then setting a budget, and finally tracking your expenses. Each step is presented as a separate task, making it easier for you to focus and complete each one.

The study

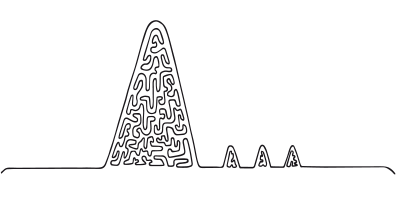

One study that encapsulates the power of sequencing in design was conducted by Robert B. Cialdini, who analyzed the effectiveness of breaking down complex processes into a series of ordered steps for the purpose of enhancing compliance. Cialdini’s work discovered that people are more likely to complete a task if it is presented in smaller, sequential steps as opposed to a single, overwhelming request.

In the study, two groups were presented with a task: one received the task as a single, complex request, and the other had the task broken down into smaller, sequential steps.

The results were telling. The group that received the task in smaller steps showed a compliance rate of 65%, whereas the group given the complex task in one go had a significantly lower compliance rate of 35%. This notable difference in compliance revealed that people are more inclined to complete a task if they receive it as a series of manageable steps.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Sequencing is employed to simplify complex tasks or operations by organizing them into a series of smaller, straightforward steps. The primary goal is to reduce the cognitive load on the user, making it easier to complete tasks and achieve objectives. This pattern is especially useful in cases where users may feel overwhelmed by the complexity or the number of steps involved in a particular activity.

The technique focuses on breaking down a complex task into a series of smaller, manageable actions, usually intended to be completed in a specific order. It guides the user through a process, like the steps in a software installation wizard.

It is a similar technique to chunking, which aims to make complex information or sets of data easier to understand and remember by dividing them into smaller, manageable groups. While both can be used in tandem for effective design, they each serve distinct primary functions.

Sequencing is not just about breaking down complex tasks; it’s about presenting them in a sequence that optimizes user engagement and task completion. Task-sequencing is generally relevant to any working environment characterized by demanding tasks, task variety, and objectives related to productivity and safety (Lodree et al., 2009). However, while task-sequencing has an overall positive effect on time on-task and task-completion but had little effect on accuracy (Ramsey et al., 2010).

One of the key psychological principles behind sequencing is the Cognitive Load Theory. This theory posits that our working memory has a limited capacity to process information. By breaking down tasks into smaller steps, sequencing reduces the cognitive load, making it easier for individuals to complete tasks without feeling overwhelmed.

Another principle that supports sequencing is the Goal-Setting Theory, which suggests that setting specific and achievable goals can significantly improve performance. Sequencing inherently involves setting mini-goals, each representing a step in the sequence, thereby increasing the likelihood of task completion.

Self-Efficacy Theory, proposed by Albert Bandura, posits that individuals are more likely to engage in activities where they have high self-efficacy, or belief in their capabilities to execute the tasks. Sequencing can boost self-efficacy by providing small, achievable goals. As individuals complete these smaller tasks, their belief in their ability to complete the larger, overarching task increases, thereby enhancing motivation and the likelihood of task completion.

Designing products with Sequencing

One of the primary goals is to decompose intricate tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. These steps can be sequential, forming a task flow, or listed items to be completed independently.

When you break down a task, each subtask should have a clear objective. When sequencing tasks, consider what the user needs to do, what can be automated by the system, and what information is essential. The aim is to eliminate any unnecessary steps or information, making the task more streamlined. By using conditional content, subsequent steps can be adapted to user inputs during earlier stages.

- Split up complex tasks

Lower the cognitive load needed to complete complex tasks by breaking them down into small, easily completed actions that are steps in a sequence or simply a list of items that need to be completed to advance through the system. - Set clear objectives for subtasks

Each subtask should be specified in terms of objectives so that the whole area of interest is covered. This ensures that every part of the primary task is addressed adequately, leaving no gaps in the process. - Set expectations. Set expectations as to how many steps are left before the entire sequence has been completed.

- Remove what is not needed

As you break down a complex task, take note of what users need to do, what the system can do, and what information the user needs. Sequencing into multiple steps allows for conditioning the content shown depending on earlier input, potentially helping to remove steps previously deemed necessary.

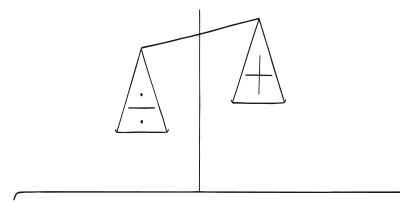

A 2017 study by Cockburn, et. al. found strong evidence for recency effects when applying the sequencing pattern – meaning that the last interactions in a sequence have a significant impact on user preference. This suggests that ending a sequence with a positive interaction could lead to a more favorable overall impression of the system. The study suggests that the effects of recency may be temporary, meaning that the most recently encountered positive or negative stimuli could have a short-term impact on user preference.

The same research did not find evidence for primacy effects (as suggested by the Serial Positioning Effect), indicating that the initial interactions in a sequence may not be as influential as previously thought. This could mean that designers might focus less on the “first impression” and more on the “last impression.”

With this in mind, consider:

- Ending on a high note

Given the strong recency effects, designers should consider ending interaction sequences with positive experiences to leave a lasting good impression. - Minimizing negative interactions towards the end

Since negative recency effects were also observed, it would be beneficial to avoid ending sequences with frustrating or complex tasks. - User retention

As the user’s retrospective assessment of experience influences their willingness to repeat an interaction, focusing on creating a positive ending could improve user retention rates.

Ethical recommendations

Sequencing, while generally employed to simplify complex tasks, can also be misused. One form of misuse could be deliberately designing a sequence that makes it difficult for users to exit a process once they’ve begun, essentially trapping them in a commitment loop. For example, e-commerce platforms might use sequencing to guide users through a complex checkout process but make it unclear how to remove items from the cart or how to avoid signing up for additional services. This could lead to unintentional purchases or commitments, thus exploiting the user’s cognitive load for commercial benefit.

Another potential misuse involves excessive ‘gamification’ of sequences, which may cause users to engage in repetitive tasks that offer little to no actual value. This could amount to a waste of time and even lead to compulsive behaviors, particularly when coupled with other techniques such as rewards or achievements.

Consider:

- Transparency

Always be transparent with users about the steps involved in a sequence and what each step entails. This helps the user to make informed decisions. - Exit options

Ensure that there are clear and easily accessible options for exiting the sequence at any point. This respects user autonomy and decision-making. - Value alignment

Make sure that the sequence aligns with the genuine needs and wants of the user. Avoid sequences that lead to unnecessary upsells or unwanted commitments.

Real life Sequencing examples

Mailchimp

The email marketing service guides users through the campaign-creation process in a sequential manner, preventing overwhelm and mistakes.

Duolingo

The language learning app breaks down lessons into small, manageable parts, guiding the user through a sequence of increasing difficulty.

When new users sign up, they are guided through a sequence of steps to complete their profile, thus encouraging fuller engagement with the platform.

Trigger Questions

- Are we breaking down complex tasks into simpler steps?

- Are we providing a clear path that guides users through these steps?

- How can we incorporate progress indicators?

- Are there any ethical concerns related to the sequence?

- Could the sequence be simplified further to lower cognitive load?

- Are we clearly communicating what each step entails and requires?

Pairings

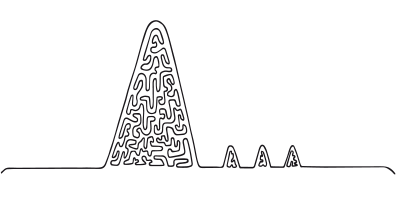

Sequencing + Goal-Gradient Effect

In e-commerce checkouts, the sequence of steps to finalize a purchase can be integrated with a progress bar (Goal-Gradient Effect), indicating how close the user is to completing the purchase.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

Our motivation increases as we move closer to a goal

Sequencing + Rewards

Online learning platforms often employ a sequence of lessons paired with rewards upon completion. Duolingo is an example where sequencing is used to break down language learning into individual lessons and units, with rewards provided at each milestone.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

Use rewards to encourage continuation of wanted behavior

Sequencing + Peak-End Rule

Combining Sequencing with the Peak-End Rule can be highly effective. For example, a fitness app could sequence workouts to start with simpler exercises and end with a satisfying cool-down session, ensuring that the user’s last memory is a positive one.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Sequencing + Serial Positioning Effect

Since Sequencing involves breaking down tasks into smaller actions, it can be paired with the Serial Positioning Effect to emphasize the first and last tasks in a sequence. This could be useful in educational platforms where the introduction and conclusion of a lesson are designed to be particularly engaging or informative.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

We remember the first and last items in a list better

Sequencing + Loss Aversion

This principle can be effective when a sequence of steps or tasks has started but is not yet complete. By highlighting what users stand to lose if the sequence is not completed, Loss Aversion can motivate them to see tasks through to the end. For example, online courses often employ this by showing progress bars or percentages, subtly communicating what you stand to “lose” if you don’t complete the course.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Sequencing + Endowment Effect

Sequencing can be paired with the Endowment Effect to give users a greater sense of ownership over the process or the end result. When users complete parts of a sequence, their emotional investment in the process or product grows. This can be seen in customizable product experiences where the user follows a sequence of choices to personalize a product. As they go through each step, they become more committed to the end product, perceiving it as more valuable because they “created” it.

Break down complex tasks into small and easily completed actions

We value objects more once we feel we own them

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Plans and the structure of behavior by Pribram, Miller & Galanter

- Working Minds: A Practitioner's Guide to Cognitive Task Analysis by Crandall, et. al.

- How to improve your UX designs with Task Analysis at The Interaction Design Foundation

- Working memory at Wikipedia (en)

- Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: the foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(2), 195.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

- Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Ramsey, M. L., Jolivette, K., Puckett Patterson, D., & Kennedy, C. (2010). Using Choice to Increase Time On-Task, Task-Completion, and Accuracy for Students with Emotional/Behavior Disorders in a Residential Facility. Education and Treatment of Children, 33, 1-21.

- Lodree, E. J., Geiger, C., & Jiang, X. (2009). Taxonomy for integrating scheduling theory and human factors: Review and research opportunities. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 39, 39-51.

- Paas, F., & Van Merriënboer, J. (1994). Instructional control of cognitive load in the training of complex cognitive tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 6(4), 351–371.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705.

- Pribram, Karl H.; Miller, George A.; Galanter, Eugene (1960). Plans and the structure of behavior. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 65

- Crandall, B., et. al. (2006). Working Minds: A Practitioner’s Guide to Cognitive Task Analysis<. MIT Press.

- Cockburn, A., Quinn, P., & Gutwin, C. (2017). The effects of interaction sequencing on user experience and preference. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 108, 89-104.