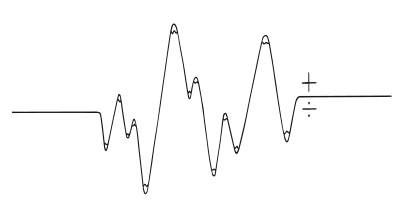

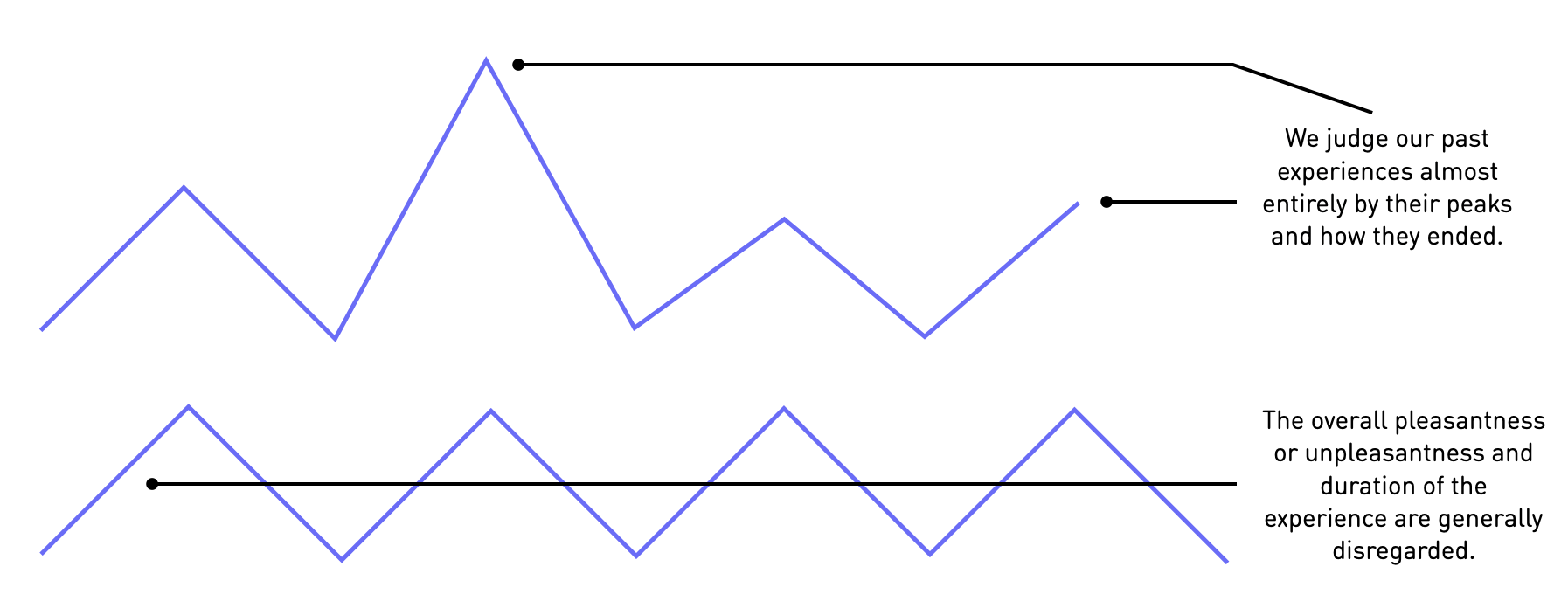

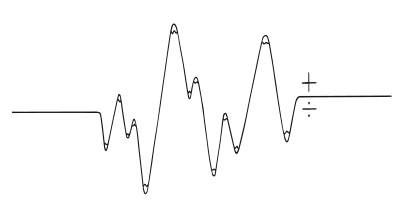

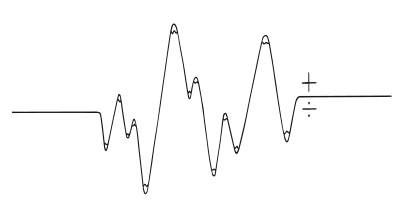

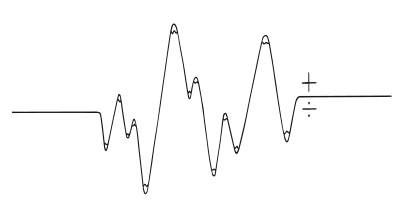

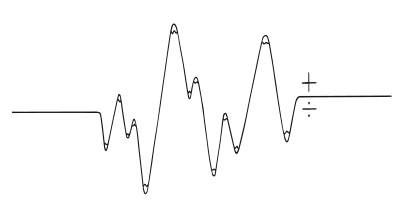

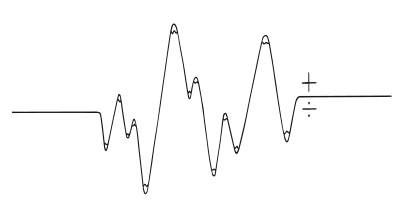

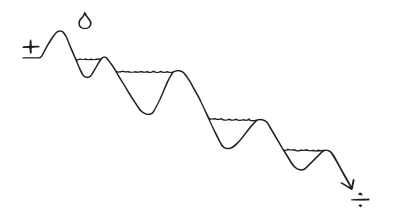

The Peak-End Rule suggests that people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its most intense point (the peak) and at its end, rather than the total sum or average of every moment of the experience.

Imagine a family visit to an amusement park. The day is filled with various rides and activities, some more enjoyable than others, but two key moments stand out: the exhilarating peak of riding the largest roller coaster and the thoughtful end where the family enjoys a spectacular fireworks display before leaving the park. Despite long lines and a mid-day downpour, the family’s overall memory of the visit is overwhelmingly positive, primarily shaped by the thrill of the coaster and the beauty of the evening’s end. This scenario demonstrates how the peak-end rule operates in everyday experiences, where the most intense and the final moments disproportionately influence how the entire day is remembered and judged.

Now, consider a user’s journey through a mobile health app designed to encourage daily exercise. Similar to the amusement park experience, the user’s interaction with the app involves various elements, but two aspects are carefully crafted to stand out: a mid-week challenge that pushes their limits (the peak) and a satisfying summary of weekly progress shown every Sunday night (the end). Even if the user faces days of low motivation or minor app glitches, their lasting impression of the app is likely to be positive if the challenging, engaging peak and the rewarding conclusion are impactful enough. This digital experience, guided by the peak-end rule, ensures that users remember the app favorably, increasing the likelihood of continued use and positive word-of-mouth recommendations.

The study

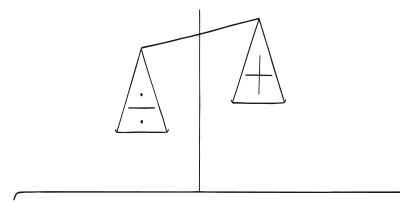

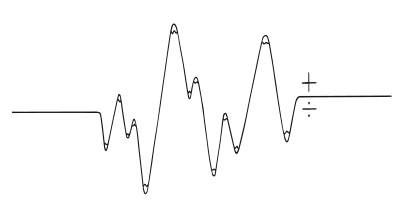

One of the most influential studies demonstrating the Peak-End Rule was conducted by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Barbara Fredrickson in the early 1990s. They explored how people’s memories of painful experiences were affected by the intensity of the peak pain and the end pain. In their experiment, subjects were subjected to two conditions of cold-water hand immersion: one short but intense, and the other longer but ended on a less intense note. Surprisingly, subjects preferred to repeat the longer experience because it had a less painful ending, despite its greater overall discomfort. This study vividly illustrates how our memories and judgments of an experience are not a sum of total moments but are disproportionately influenced by the intensity of the peak moments and the final part of the experience.

Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401-405.

The Peak-End Rule was first articulated by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Barbara Fredrickson in the 1990s. Their groundbreaking research into the nature of human memory and evaluation revealed that people’s recollections of past experiences are not comprehensive but are instead disproportionately influenced by the moments of greatest intensity (peaks) and the final moments (ends) of those experiences. This discovery challenged the previously held assumption that experiences are evaluated on an average basis of all moments. Kahneman and Fredrickson’s work demonstrated that in recalling experiences, the human mind simplifies complex information, focusing on notable highlights and the conclusion, which then form the overall memory of the event.

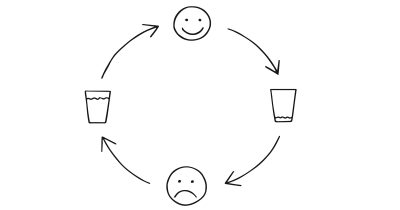

This pattern has profound implications across various fields, particularly in designing user experiences where memory of the product or service significantly impacts future decisions and loyalty. The primary goal is to strategically enhance the most memorable parts of the experience to positively influence overall perception and satisfaction.

From a cognitive psychology perspective, the Peak-End Rule illustrates how heuristic shortcuts simplify the complexity of human memory and judgment. When recalling past experiences, the brain tends to emphasize moments that are emotionally significant or conclusively meaningful, thereby streamlining the process of recall and evaluation. This heuristic helps individuals make quick decisions based on complex experiences without needing to recall every detail.

The rule’s influence is significant because it can dictate the overall impression of an experience, affecting future behavior and choices. In designing experiences, whether in service delivery, user interface, or customer journey mapping, recognizing the weight of peaks and ends can be pivotal. It suggests that even if some parts of an experience are suboptimal, ensuring high points and positive endings can leave a lasting good impression, encouraging continued engagement and positive feedback from users.

The memorability of the peak in any experience can be largely attributed to our brain’s wiring to prioritize emotionally charged events. This tendency is rooted in evolutionary psychology, where intense emotions signal events of importance, demanding attention and retention. Research supports this, indicating that emotional intensity enhances memory retention, making these peak moments stand out from the rest of the experience. Furthermore, this bias toward intense emotional experiences also plays a crucial role in shaping our nostalgic preferences, as these memorable events often define our recollections and sentimental longing for the past.

The end of an experience is disproportionately memorable due to what is known as the recency bias, part of the broader serial position effect that also includes primacy bias. While primacy bias explains our tendency to remember the beginning of a sequence, recency bias focuses on our enhanced memory for the most recent events. This is because the last parts of an experience are still fresh in working memory when the experience concludes, making them more accessible for recall. The end of an experience, thus, has a heightened impact on our overall perception and memory of the event, often overshadowing many other aspects of the experience.

Designing products using the Peak-End Rule

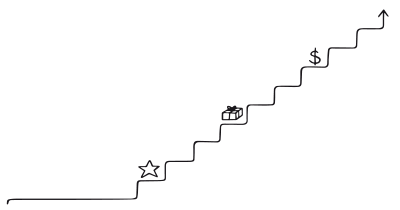

Understanding and applying the Peak-End Rule effectively in product design means focusing on creating a powerful and positive final impression, along with memorable high points throughout the user journey. This approach can significantly influence how users recall their experience, thereby affecting their satisfaction and long-term engagement with the product.

Identify the most emotionally charged points in the user journey—these could be completing a challenging level in a game, achieving a milestone in an app, or successfully finishing a complex task in a software tool. Enhance these peaks with elements that amplify satisfaction, such as immediate positive feedback, visually appealing animations, or interactive elements that celebrate the user’s achievement. This not only makes the experience enjoyable but also memorable, ensuring that these peak moments leave a strong positive impact.

The way an experience ends is critical to how it’s remembered. Focus on making the last interaction as smooth and positive as possible. For instance, in an e-commerce setting, the checkout process should be effortless, and the order confirmation page could include a thank you note or a small discount on future purchases. For a service-based application, consider a sign-off that reaffirms the value the user received, possibly through a summary of benefits or a personalized message that encourages future interaction.

To ensure that the peak and end moments are not overshadowed by usability issues, it’s crucial to streamline the entire experience. This includes simplifying navigation, optimizing loading times, and making sure instructions are clear. Remove any potential friction points that could detract from the positive aspects of the experience, ensuring that users remain focused on the benefits rather than getting frustrated by the interface or process.

It’s equally important to manage and mitigate any negative experiences throughout the user journey. If a negative peak occurs, counteract it with multiple positive interactions that can help balance the overall experience. For example, if a user encounters an error, follow up with exceptionally helpful customer support, an apology, or even compensation like a coupon or free upgrade.

The final interaction should leave the user feeling successful and valued. This could be through a well-crafted follow-up email, a rewarding summary of the user’s achievements, or an encouraging invitation to return. Ensuring that the user’s last interaction is positive reinforces their overall positive perception of the entire experience.

Your goal as a designer applying the Peak-end Rule is to create a user experience where the high points and the conclusion drive an overwhelmingly positive memory, significantly influencing the user’s perception and decisions regarding the product.

Ethical recommendations

The Peak-End Rule, while powerful in shaping user perceptions and experiences, can be susceptible to unethical use. By manipulating the peak and final moments of an experience, organizations might overshadow substantial deficiencies or problems that occurred during the process. For example, a service provider might focus on creating an exceptionally positive final interaction to gloss over poor service quality or product issues experienced earlier, thereby skewing a customer’s overall perception of the experience. Such manipulation can lead to repeated customer engagements based on misleading impressions, which may ultimately erode trust and satisfaction when customers realize the inconsistency.

To ensure that the Peak-End Rule is applied in an ethical and user-centric manner, consider the following best practices:

- Be transparent

Always maintain transparency about what users can expect from their entire experience, not just the highlights or ending. This includes being clear about any potential downsides or limitations of the product or service. - Maintain a consistent experience quality

While it’s beneficial to enhance peak and end moments, it’s crucial to ensure that these improvements are representative of the overall quality and value of the experience. Avoid creating peaks or positive endings that are disproportionately better than the rest of the experience. - Listen to users

Regularly solicit and incorporate user feedback to understand their genuine perceptions of all phases of the experience. This feedback can guide ethical improvements that align with user needs and expectations. - Balance enhancement with honesty

Enhance peak and end moments in ways that are honest and beneficial. For instance, if a product or service naturally includes less appealing aspects, address these directly with the user and provide support or solutions rather than merely compensating with unrelated positive experiences. - Avoid exploitation

Do not exploit the Peak-End Rule to mask significant problems or to manipulate users into overlooking serious issues. Such practices can lead to long-term damage to reputation and user trust.

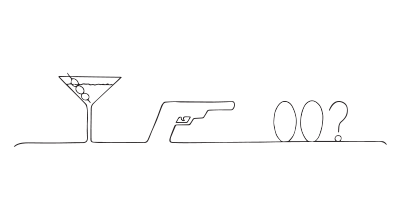

Real life Peak-End Rule examples

Zappos

Zappos uses the Peak-End Rule by upgrading shipping to next-day delivery unexpectedly, creating a peak surprise moment that customers remember.

Apple

Apple leverages this rule during product launches with meticulously planned keynotes that peak with groundbreaking product reveals and end with hands-on sessions for immediate engagement.

Disney

Disney Parks excel at implementing the Peak-End Rule by ensuring that the parades and fireworks at the end of the day are spectacular, overshadowing any earlier inconveniences like long waits.

Trigger Questions

- What moment in our user journey has the highest emotional impact?

- How can we enhance the final touchpoint to leave a lasting positive impression?

- Are there any negative aspects at the end of our user experience that could overshadow the positives?

- What feedback have we received about the peak and end moments of our product experience?

- How can we consistently measure the effectiveness of our peak and end adjustments?

- What innovative approaches can we employ to create memorable peaks and satisfying conclusions?

Pairings

Peak-End Rule + Storytelling

Storytelling naturally incorporates peaks (climactic points) and ends (conclusions), making it an ideal companion for the Peak-End Rule. Together, they create a memorable narrative arc that can significantly enhance the emotional impact of the experience.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

We engage, understand, and remember narratives better than facts alone

Peak-End Rule + Rewards

Integrating rewards at the peak and end moments of an experience can reinforce positive emotions and satisfaction. This combination ensures that rewards align with the most memorable parts of the user experience, thereby maximizing their impact.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Use rewards to encourage continuation of wanted behavior

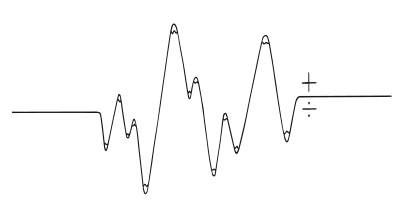

Peak-End Rule + Feedback Loops

Feedback loops can ensure that the peak and end moments are optimized based on user behavior and preferences. This responsive adaptation can help maintain the relevance and effectiveness of the peak and end moments over time.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

We are influenced by information that provides clarity on our actions

Peak-End Rule + Framing Effect

Using the framing effect to highlight the positive aspects of peak and end experiences can alter users’ perceptions, making these moments seem even more significant and positive.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

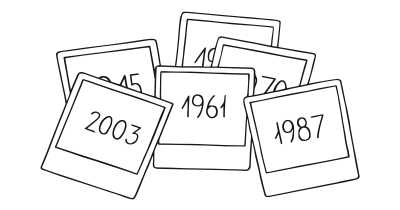

Peak-End Rule + Nostalgia Effect

Leveraging nostalgia at the peak or end of an experience can enhance emotional resonance and memorability. This can be particularly effective in marketing campaigns or product interfaces that evoke past memories to create a bond with the user.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Reminiscing about the past makes us downplay costs

Peak-End Rule + Priming Effect

Integrating the Peak-End Rule with the priming effect can make the final and peak moments more impactful. By subtly priming users throughout their interaction with specific cues and reminders, their perceptions and memories of the peak and end moments can be significantly enhanced. For instance, priming users with positive messages or visuals before a transaction can make the payment process feel more satisfying.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Decisions are unconsciously shaped by what we have recently experienced

Peak-End Rule + Loss Aversion

This combination can be particularly effective in subscription-based or renewal scenarios. By emphasizing what users stand to lose if they do not renew or continue (such as loss of data, loss of status, or ending on a negative note), coupled with a positive peak-end experience, users are more likely to continue the service to avoid negative outcomes.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Peak-End Rule + Sunk Cost Bias

Pairing the Peak-End Rule with the psychological tendency of sunk cost bias, where users continue a behavior or endeavor as a result of previously invested resources, can be powerful in membership and ongoing training programs. Highlighting the culmination of what has been learned or achieved at the end of a subscription period can motivate users to renew, driven by the desire not to waste the effort they have already invested.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

Peak-End Rule + Social Proof

Combining the Peak-End Rule with social proof involves showcasing user testimonials or reviews that highlight positive peaks and ends experienced by others. This method can be particularly effective in environments where users might be making decisions based on the perceived experiences of their peers, such as in e-commerce. Displaying reviews that emphasize positive last impressions or peak experiences can influence potential customers to make a purchase, expecting a similarly positive experience.

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you build lasting habits, facilitate behavioral commitment, build lasting habits, and understand the human mind. It is presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Evaluation by moments by Kahneman

- Peak-end Rule

- Peakend rule at Wikipedia (en)

- Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401-405.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Redelmeier, D. A., & Kahneman, D. (1996). Patients' memories of painful medical treatments: Real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain, 66(1), 3-8.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300-319.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 14(4), 577-606.

- Miron-Shatz, T., Stone, A., & Kahneman, D. (2009). Memories of yesterday's emotions: Does the valence of experience affect the memory-experience gap? Emotion, 9(6), 885-891.

- Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 203-253.

- Harrison, Chris; Amento, Brian; Kuznetsov, Stacey; Bell, Robert. (2007). "Rethinking the Progress Bar”. Proceedings of the 20th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology. (pp. 115-118).