Persuasive Patterns: Restructuring

Framing Effect

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

Framing refers to the practice of presenting information in a particular way to influence judgment and decision-making.

Imagine you’re at a grocery store, standing in front of two bins of apples. One bin has a sign that says “90% fat-free,” while the other says “contains 10% fat.” Even though both statements mean the same thing, you’re more likely to choose apples from the “90% fat-free” bin. This is an example of framing, where the way information is presented affects your decision-making process. Research by Natalie Gold and C. List suggests that the order in which propositions are considered in different presentations of a decision problem can lead to different decisions (Gold & List, 2004).

Now, consider an online subscription service that offers two payment plans. Plan A is framed as “Save $10 every month,” while Plan B is framed as “Avoid a $10 monthly surcharge.” Even though both plans offer the same financial benefit, users are more likely to opt for Plan A because of the positive framing. This is similar to the grocery store example, where the framing of information affects user choices.

The study: The Asian Disease Problem

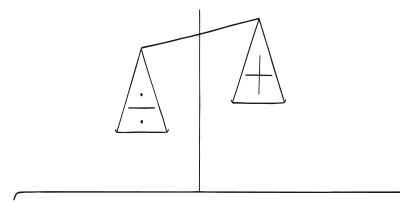

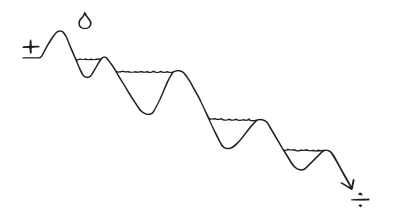

One of the most cited studies that explore the power of framing is the “Asian Disease Problem,” conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1981. In this experiment, participants were presented with a problem involving a hypothetical disease outbreak expected to kill 600 people. Two different programs were proposed to combat the disease, each framed differently but mathematically identical. When framed in terms of lives saved (“200 people will be saved”), a majority of people chose the certain Program A. However, when the same program was framed in terms of lives lost (“400 people will die”), people were more likely to opt for the riskier Program B. The results were striking: 72% opted for the safe option when it was framed positively, but only 22% chose it when framed negatively.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453-458.

The concept of framing is rooted in psychology and communication theory, positing that the way information is presented can significantly affect how it is interpreted and acted upon. It plays a crucial role in areas such as marketing, policy-making, and user experience design. The primary goal of framing is to present information in a manner that aligns with desired outcomes, such as encouraging certain behaviors or opinions.

The Framing Effect demonstrates how the context, wording, and presentation of information can significantly impact judgment and decision-making. It reveals that people’s choices are not always rational and can be swayed by how options are framed – as losses or gains, risks or benefits. Understanding this pattern is crucial in areas like marketing, policy-making, and user experience design, where how something is said can be as important as what is said.

Choices are subject to the way they are framed, influenced by different wordings, reference points, and areas of emphasis. The framing often focuses on either the positive gain or negative loss related to a choice, playing into our natural tendency to avoid loss. This inclination toward loss aversion is well-documented in “prospect theory,” developed by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. According to this theory, losses weigh heavier on our minds than equivalent gains. Because of this, we gravitate toward options framed in terms of sure gains rather than probable gains, and likewise prefer probable losses to sure losses.

The human mind often utilizes shortcuts, or “heuristics,” to expedite the decision-making process. Two such heuristics relevant to framing are the availability and affect heuristics. The availability heuristic describes our tendency to use easily recalled information when making future decisions. The framing effect has been observed to be more prevalent in older adults, possibly because they have more limited cognitive resources and therefore lean on information presented in an easily digestible manner.

The framing effect has a dual role: it can both impair and improve decision-making. On the downside, poor framing can lead us to make inferior choices. However, understanding the framing effect can also be empowering. By being aware of how framing influences decisions, we can present our information more effectively, thereby making our work more persuasive and impactful.

Designing products with the Framing Effect

One way designers can use framing is by manipulating context, words, or imagery to influence perceptions. For example, a “Service Fee” can be renamed “Buyer Protection Fee” to shift the perception of the same service. This reframing not only assures customers that the fee serves a purpose but also gives them confidence that they are taking extra measures to safeguard their purchase.

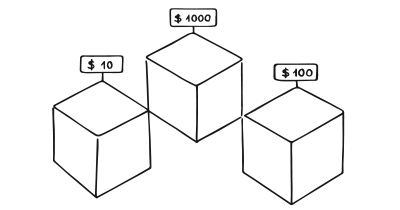

Statistics offer another area where framing can be particularly powerful. Consider a product with a 3 out of 5-star rating. While this might seem mediocre at first glance, framing that rating against a competitor’s 2-star rating suddenly puts it in a more positive light. Here again, the emphasis is on providing accurate and relevant context that aids the user in making a more informed choice.

Another tactical application of framing in product design is creating a sense of urgency or fear of missing out (FOMO). Studies have shown that framing a marketing message as a potential loss is often more effective than framing it as a gain. For example, a message stating, “Don’t lose your offer” could be more effective in prompting user action compared to “Here’s an offer.” This speaks to the psychological principle that losses generally have a greater emotional impact than gains.

Hedonic Framing

Rooted in behavioral economics, Hedonic Framing focuses on framing options in a way that highlights their benefits making them more appealing based on the Value Function and Prospect Theory. Here’s how designers can apply this concept:

- Segmentation of gains

Break down benefits into smaller, separate units. For example, if offering multiple features in a product or service, highlight each benefit individually rather than combining them. This method increases perceived value as users feel they are getting more. - Integration of losses

Conversely, when presenting costs or negatives, integrate them into a single frame. For instance, bundle costs in a pricing structure, so they appear as one lump sum. This approach reduces the negative impact that might arise from seeing multiple disadvantages. - Silver lining framing

When presenting something negative, always pair it with a positive aspect. For example, if a product is expensive, emphasize its high quality or long-term savings. This pairing can help mitigate the negative aspect with a positive one.

Other ways of framing

Beyond Thaler’s Hedonic Framing these strategies can also help shape perceptions and decisions:

- Euphemistic framing

Use language that softens the impact of less favorable aspects. Instead of saying ‘cheap’ or ‘low cost,’ which might imply low quality, use terms like ‘economical’ or ‘value-driven.’ - Endowment Effect utilization

Frame product ownership in a way that allows users to feel a sense of possession even before purchase. For instance, use phrases like ‘your future car’ or ‘when you start using this software.’ This approach can increase the perceived value through psychological ownership. - Visual framing

Apart from textual framing, use visual elements to reinforce positive aspects. Bright, appealing images and graphics can be used to draw attention to the benefits while subtly downplaying the less attractive features. - Temporal framing

Present benefits as immediate and losses as distant. For example, for a fitness app, emphasize immediate access to workouts and community while framing the subscription cost as a long-term, infrequent expense. - Contextual comparison

Frame your offerings in a way that they seem superior in the given context. If your product is more expensive than others, frame it in a premium context, comparing it with even higher-end products to make it appear reasonably priced.

When utilizing the Framing Effect, specifically consider:

- Choice architecture

Frame choices in a way that guides users toward making the decision you want them to make. For example, set the most favorable option as the default. - Positive/negative framing

Understand that people react differently to positive and negative framing. Use positive framing to encourage action and negative framing to discourage undesirable behaviors. - Bundle pricing

Frame bundled products as a value package, emphasizing the cost-saving aspect. - Clarity and simplicity

Frame messages in a clear and straightforward manner to avoid confusion and facilitate better decision-making. - Emphasizing benefits

Frame product features as benefits to the user, making the value proposition clear. - Social Proof

Frame your product as the choice of experts or large numbers of people to leverage authority and consensus.

Ethical recommendations

Given the substantial impact framing can have, ethical considerations are integral. The framing effect can impair decision-making by emphasizing lesser options or information. This can result in poor choices both in minor consumer decisions and significant life choices. Conversely, a mindful use of framing can enable more effective communication and persuasion, which, when used responsibly, can be advantageous in professional and personal settings. Ethical application of framing means avoiding misleading or manipulative tactics and striving for transparency and honesty.

For example, framing an offer to exploit loss aversion can induce unnecessary purchases, contributing to overconsumption or financial strain for the consumer. Similarly, framing can be used to trivialize or obscure important details or risks, thereby hindering informed decision-making. This is particularly concerning in sectors like healthcare or finance, where decisions have significant, long-term consequences.

Consider:

- How the user benefits

Always prioritize the user’s needs and benefits over mere business objectives. Framing should help users in making better decisions rather than leading them into choices they might later regret. - The choice architecture

When framing options, give users a well-rounded view rather than hiding or downplaying certain options. If there are pros and cons, present them in an easy-to-understand manner. - Getting informed consent

If the application involves critical user data or any long-term commitments, make sure the user is not just passively agreeing but is actively making an informed choice. Framing should not be employed to cloud judgment or disguise consent.

Real life Framing Effect examples

Amazon Prime

Amazon frames its Prime subscription as a loss if not utilized, with phrases like “Unlock savings with Prime” or “You could be saving with Prime.” This plays on loss aversion, making non-subscribers feel like they’re missing out on potential savings or benefits.

Robinhood

The investment app Robinhood uses loss aversion by showing potential gains one might miss if not investing in certain stocks. The app sends notifications like “Stock XYZ is up 10%; don’t miss out,” compelling the user to act quickly to avoid missing potential profits.

Tesla

Tesla’s marketing often frames purchasing their cars as a contribution to fighting climate change, using priming to make potential buyers think beyond the car’s features to the bigger, global impact they could have by choosing Tesla.

Trigger Questions

- How are we framing the key features of our product?

- What emotional response do we want to elicit with our framing?

- How does our framing compare to competitors?

- Are we highlighting loss or gain in our message framing?

- What ethical considerations should we keep in mind?

- Does our framing align with the user's values and needs?

- How can we test the effectiveness of different framing strategies?

Pairings

Framing Effect + Social Proof

When framing is combined with social proof, the effectiveness of each pattern may be enhanced. For example, presenting user reviews and testimonials in a positive frame (“90% of users found this product helpful”) can significantly influence decision-making.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

Framing Effect + Scarcity Bias

The way limited-time offers or scarce resources are framed can significantly impact how compelling those offers appear. For example, framing an offer as “Last chance to buy!” can trigger scarcity bias more effectively.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We value something more when it is in short supply

Framing Effect + Anchoring Bias

Anchoring sets an initial point of reference that influences subsequent judgments. Framing can be used to establish that anchor more effectively.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We tend to rely too heavily on the first information presented

Framing Effect + Authority Bias

Framing can be particularly effective when combined with Authority Bias. For example, a health app might frame its exercise recommendations as “Doctor-Approved Workouts,” leveraging the authority of medical professionals to make the framed message more persuasive.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We have a strong tendency to comply with authority figures

Framing Effect + Loss Aversion

Combining framing with Loss Aversion can be powerful. For instance, a savings app might frame its message as “Avoid losing $200 a year by not saving” instead of “Save $200 a year.” The framing taps into the user’s aversion to loss, making the message more compelling.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining

Framing Effect +

Priming

Priming can set the stage for effective framing. For example, a website selling eco-friendly products might first show statistics about climate change (priming) and then frame its products as “solutions for a healthier planet.” The priming makes the framed message more impactful.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

Framing Effect + Sunk Cost Bias

When dealing with projects that have consumed significant resources but are not yielding the expected results, framing can be used to shift the team’s perspective. Instead of viewing the project as a ‘sunk cost’ that they are emotionally attached to, it can be reframed as a ‘learning investment.’ By reframing past efforts as a necessary part of the learning and creative process and marking the milestone of learning being completed, you can allow your team to make better judgments on whether to pursue ‘implementation.’

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We are hesitant to pull out of something we have put effort into

Framing Effect + Status-Quo Bias

Studies have shown that people are generally resistant to change and prefer to stick with what they know, which is known as the Status-Quo Bias. When this is paired with effective framing, it can make subscription services more compelling and harder to abandon. For example, a subscription service could frame their renewal notifications not as an “option to renew” but as a “continuation of benefits.” This plays into the Status-Quo Bias by making the default action to continue with the service, which most people are naturally inclined to do. The framing here subtly suggests that not renewing would mean losing out on something valuable, thereby making the status quo (i.e., staying subscribed) more appealing.

The way a fact is presented greatly alters our judgment and decisions

We prefer the current state instead of comparing actual benefits to actual costs

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice by Tversky & Kahneman

- The effect of framing on willingness to buy private brands by Gamliel & Herstein

- Framing

- Framing effect (psychology) at Wikipedia (en)

- Gold, N., & List, C. (2004). Framing as Path Dependence. Economics and Philosophy, 20, 253-277.

- Cockburn, A., Quinn, P., & Gutwin, C. (2006). The effects of interaction sequencing on user experience and preference.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453-458.

- Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292.

- Levin, I. P., Schneider, S. L., & Gaeth, G. J. (1998). All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76(2), 149-188.

- Druckman, J. N. (2001). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Political Behavior, 23(3), 225-256.

- Druckman, J. N., & Nelson, K. R. (2003). Framing and deliberation: How citizens' conversations limit elite influence. American Journal of Political Science, 729-745.

- Gamliel, E., & Herstein, R. (2012). Effects of message framing and involvement on price deal effectiveness. European Journal of Marketing, 46(9), 1215-1232.