User experience, Product management

Prospect Theory

When we make decisions under risk, we give disproportionate weight to losses compared to gains.

Also called: Loss Aversion Theory and Decision-Making under Risk

See also: Anchoring Bias, Endowed Progress Effect, Endowment Effect, Framing Effect, Loss Aversion, Risk Aversion, Status-Quo Bias

Relevant metrics: User Retention Rate, Conversion Rate, Risk Preference Analysis, and A/B Testing Results

Prospect Theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, is part of behavioral economics theory. It challenges the classical economic assumption that individuals are rational actors who always make decisions to maximize their utility. Instead, Prospect Theory reveals that people are generally poor at evaluating risks and tend to weigh losses more heavily than gains of the same size.

Key Takeaways

- Users prefer avoiding losses over gaining, which drives their decisions.

- Outcomes are evaluated against current situations or expectations; shifting these changes perceived value.

- Decision-making involves filtering (editing) and then choosing (evaluation).

- Use Thaler’s hedonic framing principles to structure gains and losses effectively.

- Users are risk-averse with gains and risk-seeking to avoid losses; design should reflect this.

- Cognitive biases like status-quo bias and the endowment effect shape user preferences.

- Effective design uses framing, anchoring, and reference points to influence decisions.

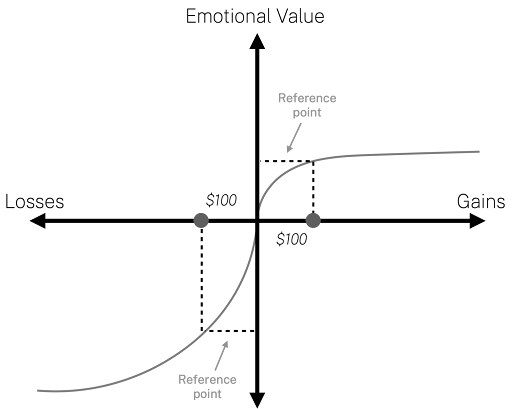

The Value Function

Prospect theory introduces a value function that is defined on deviations from a reference point (usually the status quo). The function is concave for gains, convex for losses, and steeper for losses than for gains, illustrating loss aversion.

The value function depicts how people perceive gains and losses relative to a reference point rather than in absolute terms. The value function is asymmetrical: losses loom larger than gains. This is why the function is concave for gains and concave for losses. The value function reflects a common cognitive bias (Loss Aversion) where the psychological impact of a loss is more significant than the psychological impact of an equivalent gain.

What makes the Value Function interesting is that the two axes measures something different, but very related. The vertical axis measures the emotional & psychological impact of a gain or a loss where the horizontal axis measures the absolute value of the loss or gain (money lost or gained, lives lost or saved, etc.).

In other words: in decision-making, individuals do not evaluate outcomes purely on their absolute value but a against a reference point. The reference point is typically the status quo, but could also be an expectation or a past experience. This reference point serves as a mental baseline from which gains and losses are judged. When we make a decision, we judge against the reference point and an emotional psychological value.

Let’s examine a few examples:

- Job offer. Consider a job offer scenario. If an individual currently earns $60,000 and receives a new offer for $70,000, they perceive this as a gain of $10,000. However, if they were expecting an offer of $80,000, the same $70,000 offer might be perceived as a loss relative to their expectation, even though it is still higher than their current salary.

- Investing. In investing, if a stock an investor owns was initially purchased at $50, and it rises to $70 but then falls back to $60, the investor may perceive the $10 gain as a loss because they compare it to the peak value of $70 (their new reference point) rather than their purchase price.

Changing the reference point alters the perception of outcomes, even when the absolute values remain the same.

Designing with the Value Function in mind

To leverage loss aversion in design, consider framing offers in terms of what users might lose if they don’t act, rather than what they might gain. For instance, highlighting “Don’t miss out on this limited-time offer” can be more compelling than simply promoting “Get a special discount.”

Understanding that users may be risk-averse or risk-seeking depending on the context can help in designing choice architectures that guide desired behaviors. For example, presenting safe, guaranteed outcomes for critical actions can align with users’ risk aversion tendencies.

Designs can be optimized by considering common heuristics users employ. For instance, the anchoring bias can be used to make certain options appear more attractive by setting a reference point that makes them look favorable in comparison.

Consider a scenario where a subscription service offers two plans: a standard plan and a premium plan. If the standard plan is positioned as the default (reference point), users may exhibit loss aversion by perceiving the premium plan as a loss in terms of additional cost, even if it offers more value. Conversely, if the premium plan is presented first, with the standard plan framed as a lesser option, users might feel a loss of features when downgrading, thus encouraging more premium subscriptions.

Real-world decisions are influenced by numerous factors beyond simple gain-loss evaluations. User context, cognitive biases, and emotional states are crucial for applying these concepts effectivel.

Phases of Prospect Theory

Prospect Theory suggests that decision-making occurs through a two-stage process rather than a comprehensive evaluation of all available information and options. This approach acknowledges the cognitive limitations of individuals who must simplify complex decisions. The two stages are known as the editing phase and the evaluation phase.

Where the editing phase determines what information is considered, the evaluation phase involves the application of these considerations to make a final choice.

The editing phase

In the editing phase, individuals decide which information will be considered in the decision-making process. This involves using mental shortcuts, or heuristics, to filter and organize information. During this phase, decision-makers identify the most relevant options, potential outcomes, and set their priorities. They also establish a reference point, typically the status quo or expected outcome, against which they will evaluate potential gains and losses.

This phase is critical because it shapes the decision-making process that follows. However, it is also where biases can be introduced. For instance, if certain outcomes are dismissed as improbable, or if probabilities are inaccurately assessed, the decision may be skewed from the outset. This filtering of information can lead to suboptimal choices if key factors are overlooked or misjudged.

The evaluation phase

Once the relevant information and options have been edited, individuals enter the evaluation phase. Here, they weigh the potential outcomes based on the likelihood of each occurring and their respective desirability. The evaluation phase is where the principles of Prospect Theory most clearly come into play.

Decisions are not necessarily based on rational calculations. Instead, individuals often rely on the mental shortcuts established during the editing phase. Prospect Theory posits that people tend to be risk-averse when considering potential gains and risk-seeking when trying to avoid losses. This means that individuals are more likely to make decisions that minimize potential losses rather than maximize potential gains, even if the latter would offer a higher expected value.

For example, when faced with a certain gain versus a gamble for a larger gain, most people will choose the sure thing (risk aversion). Conversely, when faced with a certain loss versus a gamble that could reduce or eliminate the loss, many will take the gamble (risk-seeking behavior). This behavior highlights the asymmetry in how people perceive gains and losses, with losses often having a more profound psychological impact.

Hedonic Framing and Thaler’s Four Principles

Hedonic Framing involves structuring outcomes in a way that maximizes perceived benefits or minimizes perceived losses. Richard Thaler proposed four principles of hedonic framing that can be strategically used to influence decision-making:

-

Segregate Gains: Since people derive diminishing pleasure from each additional unit of gain (as the value function is concave for gains), it’s more effective to present multiple smaller gains separately rather than as a lump sum.

Application Example: In a gamification context, if a user earns rewards or points, presenting these gains in stages (e.g., “You’ve earned 100 points!” followed by “Another 50 points for completing this task!”) can enhance the perceived value of the rewards.

-

Integrate Losses: The pain of a loss is felt more acutely than the pleasure of a gain, but this pain does not increase as steeply with larger losses (the loss function is convex). Therefore, it’s better to present losses in a single event rather than spread out over time.

Application Example: If a subscription service needs to raise prices, it’s more effective to do so in one significant increase rather than multiple smaller ones, reducing the frequency of perceived losses.

-

Integrate Smaller Losses with Larger Gains: People are more sensitive to losses than gains, but the sting of small losses can be softened if they are bundled with larger gains.

Application Example: When upselling a feature that has a cost, present it alongside the significant benefits it unlocks. For example, “For just $5 more per month, unlock advanced features that will enhance your experience,” makes the additional cost feel minor compared to the substantial benefits.

-

Segregate Small Gains from Larger Losses: Small gains can be powerful when they are highlighted separately from losses. Even if there’s a significant loss, the presence of a small gain can help mitigate the negative impact.

Application Example: After informing a user about the loss of a privilege or feature, immediately offering a small reward or discount (e.g., “We’re sorry you didn’t qualify for the premium feature, but here’s a 10% discount on your next purchase”) can help soften the impact of the loss.

Related concepts

The effect wears off according to Hedonic Adaptation. This concept explains how people quickly return to a baseline level of happiness after experiencing positive or negative events. In the context of Prospect Theory, once a gain (like a salary increase) is adapted to, it becomes the new reference point, and future evaluations are based on this adjusted standard.

The value function is can explain why we tend to prefer things to stay the same, or maintain the current state of affairs (the status quo). Prospect Theory helps explain this bias by illustrating how losses relative to the status quo are weighted more heavily than equivalent gains, making change seem risky and undesirable.

Once we feel that something is ours, our reference point changes. The endowment effect is the phenomenon where people value something they own more than something they do not own, even if there is no cause for this disparity. Prospect Theory explains this by showing how the loss of an owned item (relative to the reference point of ownership) feels more significant than the gain of acquiring it.

-

How do users perceive gains and losses?

Hint Users tend to be more sensitive to losses than to equivalent gains, a phenomenon known as loss aversion, which can significantly influence their decision-making process. -

How does risk influence user decisions?

Hint Users often exhibit risk-averse behavior when faced with potential gains and risk-seeking behavior when trying to avoid losses, reflecting the asymmetry in how they perceive risks and rewards. -

What role do heuristics play in decision-making?

Hint Users frequently rely on mental shortcuts or heuristics when making decisions, which can lead to systematic biases and deviations from rational behavior.

You might also be interested in reading up on:

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

- Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. HarperCollins.