Persuasive Patterns: Influence

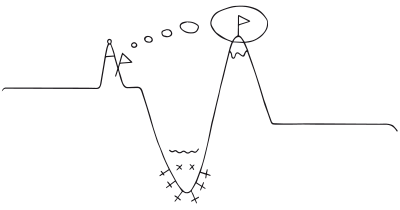

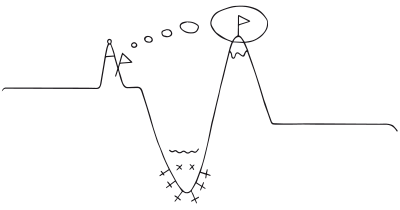

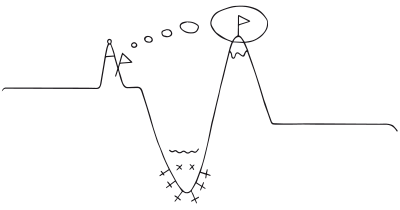

Optimism Bias

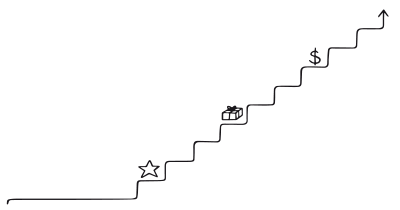

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

Optimism Bias refers to the systematic tendency of individuals to be overly positive about the outcome of planned actions and to underestimate the likelihood of negative events happening to them.

Consider a language learning app that states that with consistent daily use, learners can become conversational in a new language in about eight months. Yet, the app’s interface highlights stories of exceptional users who achieved this in just four months. Robert, a new user, believes he’ll be one of these exceptions and sets a goal to be conversational in just three months. Driven by the optimism bias, he’s convinced that his dedication will set him apart, only to feel a sense of disappointment when he aligns more with the average user progress after several months.

Overestimating trial results

A phenomenon that has intrigued researchers for years is the optimism bias. This bias refers to the tendency of individuals to hold an unwarranted belief in the efficacy of new therapies or solutions. In a systematic review of 359 randomized controlled trials involving a total of 150,232 patients, it was found that optimism bias significantly contributed to inconclusive results in 25% of these trials. This means that a quarter of the trials were affected by participants’ overly positive expectations about the outcomes, even when the evidence did not support such optimism. Such findings underscore the profound impact of optimism bias on decision-making processes, especially in contexts where individuals are presented with new and potentially beneficial solutions.

B. Djulbegovic, B., Kumar, A., Magazin, A., Schroen, A., Soares, H., Hozo, I., Clarke, M., Sargent, D., & Schell, M. (2011). Optimism bias leads to inconclusive results-an empirical study. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 64(6), 583-593.

At its core, Optimism Bias is an innate human trait that drives us to believe that our future will generally be better than our past or present, even when evidence suggests otherwise. This cognitive bias can significantly influence decision-making processes, leading individuals to take actions based on an overly positive outlook. While it can foster hope, resilience, and risk-taking, it can also lead to potential pitfalls when individuals underestimate risks or overestimate benefits. Its understanding is crucial for designers and marketers as it can guide how products or services are presented, ensuring that users make informed choices without being misled by their inherent optimistic tendencies.

Overestimating positive life events

In the late 1980s, a fascinating study emerged that demonstrated the inherent human tendency to view the future through rose-tinted glasses. Participants consistently overestimated the likelihood of positive life events, such as getting a good job or having a gifted child, while underestimating the probability of negative events, like getting divorced or facing a serious illness. This tendency to anticipate favorable outcomes, even in the face of evidence suggesting otherwise, was termed “Optimism Bias.”

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1986). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. Journal of Business, 59(4), S251-S278.

Inherent in human cognition, the optimism bias shapes how individuals perceive potential future events. It is characterized by a consistent overemphasis on favorable outcomes and a diminished focus on potential downsides. This cognitive bias influences various spheres of decision-making, from personal choices to broader societal actions. While optimism bias can drive hope, resilience, and proactive behavior, it can also lead to potential pitfalls, especially when individuals do not appropriately weigh risks against benefits.

The Optimism Bias rests upon the psychological principle of “affective forecasting,” wherein individuals predict their emotional responses to future events. This bias leads people to overestimate positive outcomes and underestimate negative ones, driven by the innate desire for positive well-being and avoidance of negative emotions.

Designing products with the Optimism Bias

By aligning your product’s messaging with this hope, you can resonate more deeply with users. For instance, instead of merely showcasing the features of a fitness app, emphasize the positive transformations users can anticipate: a healthier, fitter future self. This not only draws users in but also motivates sustained engagement. Additionally, feedback mechanisms should highlight incremental progress, further fueling optimism. However, it’s essential to remain genuine and avoid overpromising, as this can lead to disappointment and distrust.

Encouraging users to set and achieve goals is where optimism can shine. By emphasizing positive outcomes and successes, designers can motivate users to stick to routines, or keep up healthy habits. Optimism can fuel perseverance. For platforms that promote learning new skills, emphasizing potential positive outcomes (“Imagine yourself speaking fluent Spanish!”) can keep users motivated during challenging phases of the learning process. By visualizing positive outcomes, hope is fostered. For instance, meditation apps might highlight stories of individuals who found peace and clarity through regular practice.

- Reinforce visually

Visual cues, like progress bars or success stories, can further amplify the optimism bias. For instance, a project management tool might use progress charts to show an optimistic projection of project completion, while also reflecting current progress. - Periodic reflection points

Especially in long-term engagements, periodically provide users with opportunities to reflect on their progress. This can help recalibrate their optimism and ensure they remain engaged and motivated. - Align with user goals

Understand the goals and aspirations of your users. Tailor the optimistic scenarios presented in your design to align closely with these goals, ensuring relevancy.

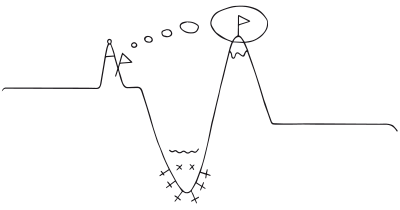

Our inherent bias for optimism can sometimes lead users to make decisions that aren’t necessarily in their best interests. It can lead to overconfidence, making choices without fully understanding the consequences, or underestimating potential risks. Designing for the optimism bias is as much about using the bias for the benefit of the user as it is working to ensure users are protected from its potential pitfalls.

One of the primary responsibilities of a designer is to prioritize the user’s welfare. For some businesses, it can be tempting to leverage the optimism bias to drive user engagement or increase conversions, but doing so for this bias can very easily erode trust and lead to negative long-term consequences for the user. Instead, designers should focus on providing balanced information, highlighting both potential rewards and risks, and enforcing reflection. This can help users make more informed decisions.

For instance, consider a financial app that provides investment advice. It’s easy to highlight stories of investors who made significant gains, but it’s equally important to provide information about potential losses and the inherent risks of investing. By providing both sides of the story, designers can ensure users have a more comprehensive understanding of potential outcomes, thus protecting them from making decisions based solely on an optimistic outlook.

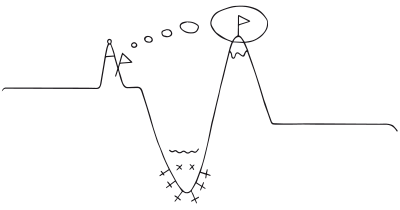

A good strategy for helping users avoid the fallacies of the Optimism Bias, is introducing safety nets or checkpoints in user flows that allow users to pause and reconsider their actions. These might include confirmation dialogues, tooltips offering additional context, or even links to further reading.

Unchecked optimism can lead to uninformed decisions. One way to strike a balance is by integrating other cognitive biases. For instance, leveraging Loss Aversion can be useful. By highlighting potential negative consequences of certain actions, you can create a sense of caution. This doesn’t mean dampening the user’s spirit but offering them a holistic view, where they see both the rewards and risks clearly. A straightforward and safer alternative can then guide them to make more informed choices.

Another effective strategy is to use the Anchoring Bias to encourage more realistic thinking. Before allowing users to dwell in an overly optimistic future, anchor them in a slightly pessimistic scenario. By initially grounding them in a more conservative or even negative outcome, their optimistic expectations can be kept in check. Techniques like simulating “pre-mortems” or employing “the future, backwards” exercises can be integrated into user flows to encourage this kind of balanced forecasting.

- Incorporate outside perspectives

Using an “outside view” to counter the optimism bias. By using external benchmarks or “base rates,” designers can help users ground their expectations in reality. For instance, comparing the user’s progress to how other users have performed in similar situations - Balance optimism with reality

While optimism can drive user engagement and motivation, it’s crucial to balance this with realistic expectations. For instance, a fitness app should promote the benefits of regular exercise but should also set realistic milestones for users to avoid disappointment.

Instead of presenting only the rosy picture, visualize a fuller perspective by showcasing both positive and negative future scenarios. This approach ensures that while users are motivated by the potential positive outcomes, they are also aware of potential challenges or downsides. Such a dual scenario approach can be particularly effective in decision-making platforms, where understanding the full spectrum of outcomes is critical.

Ethical recommendations

The Optimism Bias, while a natural human tendency, can be manipulated in design and marketing contexts to lead users into making decisions that are not in their best interest. There are several ways this bias might be exploited.

Businesses might present an overly rosy picture of potential outcomes, leading users to have unrealistic expectations. For instance, a fitness app might suggest rapid weight loss results, setting users up for disappointment when results don’t materialize as expected. By focusing solely on the positive, there’s a risk of downplaying or omitting potential negative outcomes or challenges. Financial platforms, for example, might highlight potential investment gains without adequately informing users of the risks involved. Relying on the optimism bias, platforms might encourage users to take on more than they can realistically handle, be it in terms of commitments, investments, or other endeavors.

To ensure the ethical application of the optimism bias in design, several best practices can be adopted:

- Provide full disclosure

Always provide users with a balanced view. While it’s fine to highlight potential positive outcomes, it’s equally crucial to inform users about potential risks or challenges. - User educational components

Consider integrating educational components into your design, especially in areas where decisions have significant implications. For instance, in a financial app, include resources about investment risks alongside potential benefits. - Feedback mechanisms

Implement mechanisms that allow users to receive feedback on their decisions and actions. This can help in recalibrating their expectations and actions in line with reality. - Avoid overgeneralization

While positive testimonials and success stories can be motivating, ensure they are presented as individual cases and not as guaranteed outcomes for all users. - Safety nets

Incorporate design elements that allow users to pause, reconsider, or even reverse decisions, especially in high-stakes scenarios.

Real life Optimism Bias examples

Kickstarter

The crowdfunding platform emphasizes the potential of ideas to become reality, encouraging backers to believe in the optimistic future of a project.

Fitbit

By projecting potential health benefits and showcasing success stories, Fitbit taps into users’ optimism about their health transformation journey.

Blinkist

This app, which condenses non-fiction books into short reads or listens, plays into the optimism of users who believe they can gain knowledge and improve themselves, even with limited time on their hands.

Trigger Questions

- How does our product align with users' positive expectations for their future?

- Are we making genuine promises that we can deliver on?

- How can we highlight incremental progress to foster continued user optimism?

- Are we setting realistic expectations to prevent user disappointment?

- How can we introduce checkpoints in our design to allow users to pause and reflect on their decisions?

- Are we offering any safety nets to protect users from potential pitfalls of their optimism?

Pairings

Optimism Bias + Social Proof

Combining optimism with social proof can instill confidence in users about their decisions. For instance, a fitness app might not only show the potential benefits of a particular workout regime but also showcase testimonials or success stories from other users who have achieved their goals.

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

We assume the actions of others in new or unfamiliar situations

Optimism Bias + Rewards

Pairing optimism with tangible rewards can be motivating. For example, a financial savings app might present an optimistic view of future savings while offering immediate rewards for consistent saving behaviors.

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

Use rewards to encourage continuation of wanted behavior

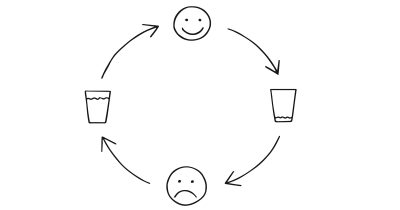

Optimism Bias + Feedback Loops

As users act on their optimism, providing feedback can help calibrate their expectations. A diet tracking app might offer optimistic projections about weight loss, while continuously updating users on their progress and adjusting future projections based on actual data.

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

We are influenced by information that provides clarity on our actions

Optimism Bias + Storytelling + Peak-End Rule

A brand might use storytelling to convey the journey of a product, starting with an optimistic vision of its creation and ending with its positive impact on the world. The narrative would focus on the most impactful moments (peak) and conclude on a high note (end) to leave a lasting impression. For instance, an eco-friendly brand sharing the story of how its products are optimistically projected to reduce environmental impact, highlighting major milestones in its sustainable journey, and concluding with its most significant achievements.

We consistently overstate expected success and downplay expected failure

We engage, understand, and remember narratives better than facts alone

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you increase conversions and drive decisions. presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- The Optimism Bias by Sharot

- Exploring the causes of comparative optimism by Shepperd, Carroll, Grace & Terry

- WordPress.com at WordPress.com

- Optimism Bias

- Optimism bias at Wikipedia (en)

- How to avoid the optimism bias when building experience strategy? by Aga Szstek at Medium

- Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21(23), R941-R945.

- Sharot, T., Korn, C. W., & Dolan, R. J. (2011). How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality. Nature Neuroscience, 14(11), 1475–1479.

- B. Djulbegovic, B., Kumar, A., Magazin, A., Schroen, A., Soares, H., Hozo, I., Clarke, M., Sargent, D., & Schell, M. (2011). Optimism bias leads to inconclusive results-an empirical study. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 64(6), 583-593.

- Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806-820.

- Barberis, N. (2013). Thirty Years of Prospect Theory in Economics: A Review and Assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1), 173-196.

- Helweg-Larsen, M., & Shepperd, J. A. (2001). Do Moderators of the Optimistic Bias Affect Personal or Target Risk Estimates? A Review of the Literature. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(1), 74-95.

- Kuzmanovic, B., Jefferson, A., & Vogeley, K. (2015). Self‐specific Optimism Bias in Belief Updating Is Associated with High Trait Optimism. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 28(3), 281-293.

- Segerstrom, S. (2001). Optimism and Attentional Bias for Negative and Positive Stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(10), 1334-1343.

- Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow (1st Edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.