Persuasive Patterns: Facilitation

Pattern Recognition

We try to recognize patterns even where there are none

Pattern Recognition in the context of persuasive design refers to the tendency to seek organization and simplification in complex or random information. The pattern taps into the human inclination to find order even when none exists, aiding in decision-making and engagement.

Imagine you’re looking at a night sky filled with stars. While there’s no actual pattern to the placement of these celestial bodies, you can’t help but see constellations, connecting dots to form shapes and figures. This is your brain’s way of trying to make sense of complexity by seeking patterns, even when none exist. Research has shown that humans have a natural tendency to find patterns in random data, a phenomenon known as apophenia (Brugger, 2001).

The same is true in the digital world. Consider a social media platform that presents you with a feed of posts from various users. The posts are algorithmically arranged, but not in any way that forms a recognizable pattern to the human eye. Yet, you might start to think that posts appearing closer to the top of your feed are somehow more relevant or important, even though they are not intentionally organized that way. This is akin to your brain’s natural tendency to seek patterns in complex data sets, a concept supported by studies on user interaction with algorithmically generated content (Eslami et al., 2015).

Don’t mind the gorilla

One study that demonstrates the power of Pattern Recognition in design is the “Gorillas in Our Midst” experiment conducted by Simons and Chabris (1999). Participants were asked to watch a video of people passing a basketball and count the number of passes. A person in a gorilla costume walks through the scene, but surprisingly, many participants completely missed the “gorilla,” focusing instead on counting passes. This study underlines how our minds filter information and create patterns to help us focus on what we deem important, often missing out on other details.

Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28(9), 1059-1074.

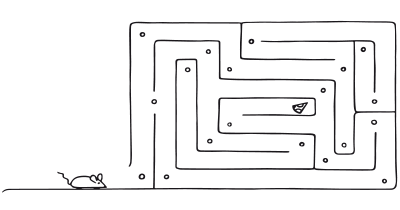

The psychological principle underlying Pattern Recognition is the human tendency for cognitive simplification. Our brains are wired to organize information into coherent patterns to reduce cognitive load and make quicker decisions.

Our brains rely on Pattern Recognition to make any experiences we have and any decisions we make effortless. By arranging information or options in a way that forms recognizable patterns, designers can help ease the cognitive load put on users and facilitate quicker processing and decision-making resulting in a more satisfying user experience.

Tapping into known patterns reduces cognitive load by offering a sense of order and familiarity. This is particularly useful when users are confronted with complex or abundant information. Tapping into our innate need to make sense of patterns can help facilitate quicker, easier decision-making and enhance user satisfaction.

Designing products using Pattern Recognition

One of the first things to consider when applying pattern recognition principles is the user’s existing familiarity with specific design elements. Icons, layouts, and navigation patterns that are familiar to users can significantly reduce cognitive load, making the interface more accessible. For instance, the widespread understanding of the shopping cart icon as a place to store items for purchase should be consistently applied across platforms to leverage user’s existing knowledge.

Another factor that warrants attention is cognitive fluency, or how effortlessly users can process information. Design features that align with user expectations tend to be processed more smoothly. Achieving cognitive fluency can range from ensuring text readability and logical flow to even aesthetic considerations. When users find the experience smooth, they are more likely to engage further, either by making a purchase or spending more time on the platform.

It’s also essential to look at the information architecture. Grouping related information together can aid quicker decision-making and also improves the user’s predictive abilities for future interactions. Maintaining uniformity in elements like color schemes or typography across different sections adds to this by enabling quicker recognition and navigation.

Adding a layer of gamification can incite curiosity and encourage pattern-seeking behavior. Playful organization or labeling of information can be a strategic way to engage users. Similarly, providing affordance cues - or “nudges”, like a “push” or “pull” sign on a door, can guide user interaction with the platform.

As you gather more data on the user’s choices and actions, you can use machine learning or simple categorization to build a profile that predicts future preferences, thus further reducing cognitive friction by presenting more personalized content.

Ethical recommendations

Tapping into users’ desire for pattern recognition in designs, while generally aimed at improving user experience, holds the potential for misuse.

One significant concern is over-engagement, where the design manipulates users into trying to keep recognizing a pattern where there is none – keeping them engaged in an activity longer than they might have intended. This could lead to negative outcomes such as procrastination or the neglect of other responsibilities.

Confirm that any applications align with user goals and expectations to avoid misleading them.

Real life Pattern Recognition examples

Grammarly

This writing assistant employs pattern recognition to suggest improvements in sentence structure. By making suggestions that read smoothly like a typical sentence (tapping into cognitive fluency), users find it easier to incorporate the changes, thus improving their writing.

Uber

When you book a ride, the app displays a map that shows real-time movement of the car. This taps into our pattern recognition ability to gauge time and distance in a familiar, real-world context, making the wait more intuitive and less frustrating.

IKEA

In their online store, IKEA clusters similar types of furniture together and employs familiar icons to indicate key features like sustainability or easy assembly. This use of pattern recognition aids users in quick and informed decision-making.

Trigger Questions

- Are we aligning with existing mental models that users already have?

- How are we grouping similar items or choices together?

- Is the pattern we're encouraging beneficial or detrimental to the user's decision-making process?

- Do we risk oversimplifying complex information?

- Are we presenting the patterns in a way that respects the users' autonomy in decision-making?

- Are we transparent about how pattern recognition algorithms influence the user experience?

Pairings

Pattern Recognition +

Set Completion

Fitness or habit-tracking apps often include a series of daily or weekly challenges. Users may notice that some challenges appear to be grouped thematically, or escalate in difficulty, and attempt to predict upcoming challenges based on past ones. The desire to complete the pattern may motivate users to continue with the app, even if the challenges are, in fact, randomly generated.

We try to recognize patterns even where there are none

Pattern Recognition + Role Playing

Online multiplayer games often have random elements—loot drops, random encounters, etc. Players might believe they see patterns in these random events (“This type of enemy always drops this type of loot”) and change their in-game behavior based on these perceived patterns. The drive to identify a pattern can make gameplay more engaging, even if the events are truly random.

We try to recognize patterns even where there are none

People act according to their persona

Pattern Recognition + Autonomy Bias

In an online learning platform, users may be given the freedom to choose the order in which they complete modules or courses. They might notice patterns, such as their performance improves when they alternate between hard and easy courses, or when they complete courses in a particular sequence. This autonomy to discover patterns could lead to better learning outcomes and greater satisfaction with the platform.

We try to recognize patterns even where there are none

We strive to feel in control

Pattern Recognition + Curiosity Effect

In Last.fm’s revamped sign-up process, the Curiosity Effect and Pattern Recognition work together to engage users more deeply. When users select artists they enjoy, the system refines subsequent suggestions, sparking curiosity about how precise the recommendations can get. This compels users to continue selecting more artists, driven by the innate human desire to identify patterns. The new design not only meets Last.fm’s business goal of collecting valuable user data but also keeps users engaged, demonstrating an effective pairing of the two principles.

We try to recognize patterns even where there are none

We crave more when teased with a small bit of interesting information

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you build lasting habits, facilitate behavioral commitment, build lasting habits, and understand the human mind. It is presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Recognition-by-components: a theory of human image understanding by Biederman

- Affordance by Norman

- What are Affordances? at The Interaction Design Foundation

- Biederman, I. (1987). Recognition-by-components: a theory of human image understanding. Psychol Rev. 1987 Apr;94(2):115-147.

- Norman, D. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design, Interactions Volume 6, Issue 3, pp 38–43

- Brugger, P. (2001). From Haunted Brain to Haunted Science: A Cognitive Neuroscience View of Paranormal and Pseudoscientific Thought. In J. Houran & R. Lange (Eds.), Hauntings and Poltergeists: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 195-213). North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Eslami, M., Rickman, A., Vaccaro, K., Aleyasen, A., Vuong, A., Karahalios, K., ... & Sandvig, C. (2015). "I always assumed that I wasn't really that close to [her]": Reasoning about Invisible Algorithms in News Feeds. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 153-162). ACM.

- Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28(9), 1059-1074.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1972). Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness. Cognitive Psychology, 3(3), 430-454.

- Fiske, S.T., & Taylor, S.E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Asch, S.E. (1952). Social psychology. Prentice-Hall.

- Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive psychology. Appleton-Century-Crofts.