Persuasive Patterns: Influence

Need for Closure

We have a desire for definite cognitive closure as opposed to enduring ambiguity

The “Need for Closure” refers to an individual’s desire for a definitive answer or clarity on a subject, as opposed to ambiguity or uncertainty.

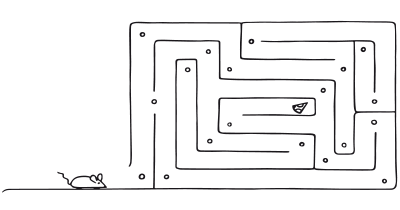

Imagine someone who has been working on a project for weeks. They’ve invested a lot of time and effort into it, and they’re close to finishing. However, they receive feedback suggesting that there might be a better approach. Instead of considering the new approach, they feel compelled to continue with their current path, even if it might not yield the best results. Their need for closure, the desire to have a definitive answer and avoid ambiguity, drives them to stick with their initial plan, even when presented with potentially better alternatives.

Now, consider a user who starts signing up for an online service. Halfway through the registration process, they realize that another platform might offer better features. However, the sign-up process on the current platform indicates that they’re “70% complete.” This progress bar, indicating how close they are to completion, taps into their need for closure. Instead of abandoning the process and starting over on a potentially better platform, they feel compelled to finish what they’ve started, driven by the desire to achieve that 100% completion.

Our need for closure impacts decision-making

In the mid-1990s, researchers Arie Kruglanski and Donna Webster embarked on a series of experiments to dive deeper into the cognitive motivations behind the human desire for conclusive answers.

In one of their notable experiments, participants were presented with ambiguous situations and were measured on their urgency to resolve them. Some participants were found to have a high need for closure, wanting immediate and definitive answers, while others were more at ease with the ambiguity, willing to explore various possibilities before arriving at a conclusion. This urgency in the high need for closure group wasn’t just a mere preference; it impacted their decision-making process, often leading them to seize on details that would provide quick answers and “freeze” on that information, ignoring subsequent details that might challenge their conclusions. This phenomenon was termed the “Need for Closure,” highlighting a fundamental cognitive difference in how individuals approach uncertainty and decision-making.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing.” Psychological Review, 103(2), 263-283.

The Need for Closure is a cognitive pattern where individuals seek resolution or clarity, especially in situations that are ambiguous or open-ended. This need can drive people to make decisions more quickly, favoring a clear path or solution rather than lingering in a state of uncertainty. In product design and marketing, understanding this pattern can help in creating experiences that provide clear answers, streamline decision-making processes, or offer resolutions that satisfy this innate psychological need.

The Need for Closure is fundamentally rooted in the human desire for predictability and the discomfort of ambiguity. It is a motivational principle where individuals seek a firm answer to a question and an aversion to uncertainty.

Sidestepping decisions by relying on other biases

Otto, Clarkson, and Kardes (2016) examined the concept of “decision sidestepping.” Their research aimed to uncover the strategies individuals employ when they have a strong motivation for closure. The study revealed that those with a high need for closure tend to sidestep the decision-making process by relying on strategies such as default bias, choice delegation, status quo bias, inaction inertia, and option fixation. These strategies are essentially shortcuts, allowing individuals to reduce the mental effort associated with decision-making. The underlying reason? To ease future decisions and minimize the discomfort of uncertainty. This study provides valuable insights into how the need for closure can influence not just the decisions we make, but also the way we approach decision-making itself.

Otto, A. S., Clarkson, J., & Kardes, F. (2016). Decision sidestepping: How the motivation for closure prompts individuals to bypass decision making. Journal of personality and social psychology, 111(1), 1-16.

Historically, the concept of the need for closure can trace its origins to early psychological theories around discomfort with ambiguity. However, it was in the 1990s, with the work of Kruglanski and Webster, that the term “Need for Closure” was formally introduced and became a focal point of study in cognitive and social psychology.

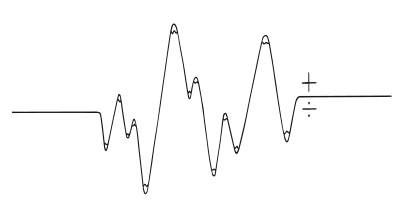

In their 1996 paper, Kruglanski and Webster identified two primary processes within the need for closure: “seizing” and “freezing.”

- Seizing

Grabbing onto information quickly to form a judgment or decision. An individual with a high need for closure might seize on the first piece of information they come across to form an opinion. - Freezing

Once an opinion or decision is formed, there’s a tendency to “freeze” on it, meaning they become closed off to subsequent information that might challenge or change that decision.

Individuals with a high need for closure tend to make decisions more quickly. They often favor clear, immediate answers over spending time deliberating multiple options or dealing with uncertainty. This urgency isn’t just a preference; it impacts their entire decision-making process. They might seize early on details that provide quick answers and then “freeze” on that information, ignoring subsequent details that might challenge their initial conclusions.

A heightened need for closure leads to an aversion to ambiguous situations. People might avoid situations, tasks, or decisions that present too many unknowns or that might not have a clear, immediate resolution.

In situations where feedback suggests an alternative approach or introduces elements of doubt, those with a high need for closure might resist the new information, preferring to stick to their current path to achieve a sense of completion faster.

Designing products with the Need for Closure

At the core of this pattern is the innate human compulsion to achieve completeness. Whether it’s filling out a profile, achieving a set goal, or watching a series of short videos, the drive to complete tasks can be harnessed to guide user behavior. For instance, platforms can prompt users by highlighting what’s left undone, subtly nudging them toward completion. But beyond just indicating incompletion, it’s also crucial to delineate a clear, straightforward path toward achieving that closure. The easier and more intuitive the path, the more likely users will be to follow through.

Ensure that your design process considers the user’s journey from start to finish. Every touchpoint should lead them closer to a sense of completion.

Simple, direct instructions and immediate feedback mechanisms can reassure users that they’re on the right track. Onboarding processes, for instance, benefit immensely from this understanding. Instead of overwhelming users with numerous options or excessive information, a streamlined, step-by-step walkthrough can help them quickly grasp the product’s core functionalities, satisfying their need for closure.

Give users something to strive for. Whether it’s profile completion on a social platform or a multi-stage checkout process in an e-commerce app, clear milestones guide users. It gives them a roadmap of what’s achieved and what remains. This not only makes the journey intuitive but also gives users a sense of progress, compelling them to see tasks through to completion.

Much like milestones, progress indicators, be it in the form of bars, percentages, or checklists, can be a powerful tool. They visually represent the user’s journey, subtly nudging them towards completion. For instance, multi-step forms with progress bars can reduce abandonment rates as users, having invested time in filling prior sections, are less likely to drop off midway.

Rather than merely focusing on what’s done, sometimes it’s essential to highlight what’s left. Platforms can use subtle cues like notifications or visual markers to indicate incomplete tasks. This plays on the user’s aversion to incompletion, driving them to act.

Identifying incompletion is half the battle. The other half is providing users with a clear, straightforward path to resolution. Making this path intuitive, with minimal steps, can significantly increase the likelihood of task completion. For instance, if a user hasn’t filled out a particular section of their profile, a direct link to that section can guide them to act.

Humans are driven not just by the need to complete but also by rewards. Consider introducing incentives for task completion. This could range from badges in a gamified environment, discounts in e-commerce platforms, or even access to exclusive content. The prospect of a reward, combined with the desire for closure, can be a potent mix.

To tap into our Need for Closure, the path to completion needs to be clear and straightforward. Closure should be attainable and decisions should be easy. While offering choices empowers users, there are moments in the user journey where too many options can be counterproductive – especially when tapping into our innate Need for Closure. Particularly at critical junctures, like finalizing a purchase, minimizing choices can reduce indecision and promote action.

One tactic playing on our need for closure is giving users a head start, artificially advancing their progress. Instead of giving a blank stamp card, offer one with a couple of stamps already on it. This initial advancement can drive users to complete the card, given they perceive they are already partway through.

Ethical recommendations

This pattern can, like many others, be manipulated in ways that are not in the user’s best interest.

- Endless loops

Some platforms, knowing the human desire for closure, may create never-ending tasks or loops, keeping users engaged far longer than they intended. This could lead to excessive screen time, distraction from important tasks, or even financial costs. - Artificial scarcity

By creating a perception that an opportunity is fleeting or a task must be completed immediately, users might be pushed into making hasty decisions they later regret. For instance, an online shopping platform might use limited-time offers or countdown timers to push sales, exploiting the need for closure to urge a purchase. - Information overload

The need for closure might be used to encourage users to provide excessive personal data, under the guise of “completing a profile” or “finishing a survey,” leading to potential privacy concerns.

To ensure that your application of the Need for Closure pattern, use these rules of thumbs as a checklist as you design with the pattern in mind.

- User control

Give users the ability to pause, save progress, or opt-out of tasks, especially those that are long or recurring. This respects their autonomy and decision-making. - Avoid artificial urgency

While it’s acceptable to highlight the benefits of completing a task, avoid creating undue pressure or urgency that might lead users to make decisions they haven’t fully considered. - Privacy first

If collecting user data, always explain why it’s needed and how it will be used. Ensure that any data collection is compliant with privacy laws and best practices.

Real life Need for Closure examples

When users have an incomplete profile, LinkedIn notifies them, often stating, “You’re just a few steps away from completing your profile.” By doing this, they not only highlight the incompleteness but also provide a clear roadmap for users to achieve closure. Furthermore, they offer rewards for profile completion, further motivating users.

Fitbit

Fitbit sets daily goals for steps, active minutes, and floors climbed. The dashboard displays how close or far a user is from achieving these goals. The visual representation of daily progress encourages users to complete their fitness goals, promoting consistent physical activity throughout the day.

Netflix

When watching a series on Netflix, the next episode starts automatically with a brief countdown, playing on the viewer’s need for closure to finish the series or at least watch the next episode. This feature increases viewing durations as users often opt to continue watching, seeking closure for the storyline.

Trigger Questions

- How can I visually represent progress or the state of completion to guide users towards achieving closure?

- In what areas can I reduce ambiguity to accelerate decision-making while still offering valuable choices?

- Are there areas in the user journey where simplifying tasks or reducing steps can satisfy the user's need for closure more efficiently?

- How can I provide immediate, clear feedback to users, ensuring they feel they're on the right track towards completion?

- How can I ensure I'm not overwhelming users with excessive information or options, thus hindering their need for closure?

- In what ways might we be inadvertently prolonging a user's journey, denying them a timely sense of closure?

- How can we balance the need for quick closure with the necessity of providing depth and detail?

- Are there areas in our design where users might feel 'stuck' or uncertain, and how can we address this?

Pairings

Need for Closure + Peak-End Rule

Experiences are largely remembered by their peaks and endings. Designing with the Need for Closure in mind ensures that the “endings” of user experiences are satisfactory and memorable, enhancing the overall perception of the product or service. Ensure that the ending moments of any interaction, purchase, or engagement are positive and memorable.

We have a desire for definite cognitive closure as opposed to enduring ambiguity

We judge an experience by its peak and how it ends

Need for Closure + Commitment & Consistency

People who have begun a task seek to complete it to attain closure. This aligns with the commitment principle where once a user commits to something (like starting a task), they are more likely to see it through. Features like streaks or daily challenges allow users to commit to a goal. Once a user starts and commits to a streak, the need for closure pushes them to maintain it.

We have a desire for definite cognitive closure as opposed to enduring ambiguity

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

Need for Closure + Curiosity Effect

Even in an environment where users desire closure, incorporating elements of curiosity can be beneficial. By offering a blend of routine and expected tasks that provide a sense of completion and novel options that pique curiosity, you can cater to the dual human nature of seeking both comfort and novelty. For example, a mobile game might offer regular levels that players are familiar with (providing a sense of closure as they complete them) while intermittently introducing surprise bonus stages or puzzles, igniting the player’s curiosity and desire to explore.

We have a desire for definite cognitive closure as opposed to enduring ambiguity

We crave more when teased with a small bit of interesting information

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you build lasting habits, facilitate behavioral commitment, build lasting habits, and understand the human mind. It is presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- The need for cognitive closure by Kruglanski & Fishman

- Motivated resistance and openness to persuasion [ by Kruglanski, et. al.

- Closure (psychology) at Wikipedia (en)

- APA PsycNet

- Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing.” Psychological Review, 103(2), 263-283.

- Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L., & De Grada, E. (2006). Groups as epistemic providers: Need for closure and the unfolding of group-centrism. Psychological Review, 113(1), 84-100.

- Kruglanski, A. W., & Fishman, S. (2009). The need for cognitive closure. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 343–353). The Guilford Press.

- Barlow, A. (1981). Gestalt Therapy and Gestalt Psychology. The Gestalt Journal, 4(2), 4-24.

- Roets, A., & Van Hiel, A. (2007). Separating ability from need: Clarifying the dimensional structure of the Need for Closure Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 266-280.

- Otto, A. S., Clarkson, J., & Kardes, F. (2016). Decision sidestepping: How the motivation for closure prompts individuals to bypass decision making. Journal of personality and social psychology, 111(1), 1-16.