Persuasive Patterns: Facilitation

Zeigarnik Effect

We remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones

The Zeigarnik Effect is a psychological phenomenon where people tend to remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than tasks they have completed. It suggests that unfinished tasks create a state of mental tension and cognitive dissonance, which improves recall ability. Leveraging the Zeigarnik Effect can motivate users to complete tasks or return to a product or service by leaving activities intriguingly incomplete or creating episodic, cliffhanger-like experiences.

Imagine you’re working on a complex spreadsheet (a not-so-thrilling task for many). You become engrossed in a particular formula, but then get interrupted by a phone call. Later, when you return to your work, you likely recall the specific formula you were working on – the unfinished task – more easily than the completed tasks you had finished before the interruption. This lingering memory of the unfinished task serves as a mental reminder to return and complete it.

Similarly, consider a popular to-do list app. The app allows users to mark tasks as completed. However, research suggests that users are more likely to remember and return to uncompleted tasks on their list. The visual presence of these unfinished tasks acts as a cue, leveraging the Zeigarnik Effect to nudge users towards completing their to-do list.

The study

In the seminal study conducted by Bluma Zeigarnik, the psychologist observed the memory differences between completed and uncompleted tasks through controlled experiments. Her experiments involved asking participants to perform simple tasks like solving puzzles or creating flat figures with clay. Once half of the tasks were intentionally interrupted, and the other half were allowed to complete without interruption.

Zeigarnik found that participants were about twice as likely to recall details about the tasks that were interrupted compared to those that were completed. These results highlight the cognitive tension created by unfinished work, suggesting that our minds remain engaged with tasks that have not reached a resolution. This engagement appears to enhance our ability to recall details about the process and status of the task, a finding that has been widely supported and expanded upon in subsequent psychological research.

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9(1), 1-85.

The Zeigarnik Effect, an intriguing aspect of human psychology, was first identified by Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik in the early 20th century. While studying under the guidance of Gestalt psychologist Kurt Lewin in Berlin, Zeigarnik observed a distinctive pattern in memory recall during her experiments. She noticed that waiters could remember incomplete orders better than those that had been fulfilled, suggesting that uncompleted tasks are easier to recall than completed ones. This observation led to her seminal research published in 1927, which subsequently gave rise to the naming of the Zeigarnik Effect.

The historical context of this pattern’s development is rooted in the broader field of Gestalt psychology, which focuses on how people interpret the world. The Zeigarnik Effect aligns with the Gestalt principles of perceptual organization and closure, emphasizing how our minds seek to complete what is incomplete.

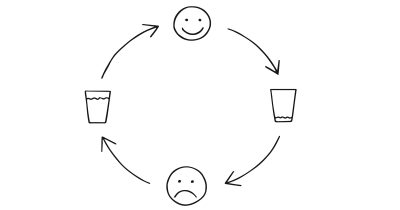

The Zeigarnik Effect centers around our brain’s preference for completion and the discomfort of open loops. It hinges on the idea that individuals remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than those they complete, due to the cognitive tension these unfinished tasks create.

This tension, often described as a state of psychological unease or arousal, acts as a persistent reminder that encourages us to return to and complete the task. Such a state is not merely a source of discomfort; it also serves a functional purpose by keeping the task salient in our memory. This principle has its roots in Gestalt psychology and its law of closure, which suggests that humans have a natural desire to see things as complete and whole. Thus, when something feels incomplete, it creates an uncomfortable, open loop that the mind seeks to close.

In cognitive terms, uncompleted tasks establish “open loops” in our working memory, which our brains prioritize resolving. This prioritization is due to our innate drive for cognitive economy – our minds strive to reduce mental load and restore a sense of cognitive equilibrium. This drive is deeply rooted in the broader theory of cognitive dissonance introduced by Leon Festinger, which posits that inconsistencies among our beliefs, values, and perceptions create psychological discomfort that we are motivated to resolve.

The persistence of uncompleted tasks in our memory is an adaptive function, enhancing our ability to manage, prioritize, and plan actions necessary for goal achievement. This mechanism ensures that important tasks are not forgotten, promoting a continuous engagement until completion. Kurt Lewin’s field theory further elucidates this by explaining that a task, once initiated, creates a task-specific tension, which is relieved only upon the task’s completion. If interrupted, the tension remains, making the associated information more accessible and memorable.

Designing products using the Zeigarnik Effect

By capitalizing on the psychological discomfort associated with incomplete tasks you can help ensure a satisfying user experience that encourages return and continued use.

By incorporating design elements such as bolding uncompleted items on to-do lists, changing the color of unfinished progress bars, or displaying icons that signal outstanding actions, designers can create potent visual reminders. These cues act as persistent nudges that encourage users to return and complete their tasks, thereby reducing the cognitive load associated with open loops and enhancing overall task management.

While progress bars are commonplace, their design can significantly influence user behavior. A partially filled progress bar, for instance, not only tracks completion but also visually represents what remains, tapping into the user’s innate desire for closure. This can be particularly impactful in apps like fitness trackers, where showing both completed activities and those pending can motivate users to complete their daily or weekly fitness goals. Further, breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable subtasks can prevent feelings of overwhelm and instead foster a sense of achievement with each small victory, maintaining engagement through a series of mini-closures.

To maintain user engagement over time, try to introduce new tasks as soon as old ones are completed. This strategy keeps the user in a continuous loop of engagement, with new challenges ready as soon as previous ones are accomplished. This not only keeps the platform dynamic and interesting but also ensures that users have always something new to look forward to, thereby maximizing retention.

Nudge with the help of User Interface design patterns

Integrating game mechanics such as points, badges, and micro-rewards for progress within tasks can significantly enhance engagement. This strategy utilizes the Zeigarnik Effect by rewarding not just the completion of a task but also the progress towards it, maintaining a user’s focus and motivation. For example, in educational apps, awarding points for each segment of a lesson completed can keep students engaged throughout the course of their study, encouraging continuous interaction with the content.

Notifications serve as effective reminders for incomplete tasks. Timely and well-crafted alerts can draw users back to tasks they left unfinished, effectively utilizing the psychological pull of the Zeigarnik Effect. Personalizing these notifications based on the user’s past behavior and preferences can make them more relevant and compelling. For instance, if a user has shown interest in certain types of articles or products, reminding them to revisit these interests can effectively bring them back to the platform.

How tasks are presented and how completion is handled can make a significant difference. Design elements that clearly show progress, as well as those that celebrate completion, can enhance satisfaction and encourage users to undertake subsequent tasks. For instance, the use of ellipses in communication to indicate ongoing threads can compel users to return, driven by a need to resolve the open loop. Breaking down content into digestible parts not only makes information easier to absorb but also keeps users coming back to complete their learning journey.

Ethical recommendations

The Zeigarnik Effect, by its nature, leverages the psychological discomfort of incomplete tasks to motivate behavior. If applied without careful consideration, it can lead to unethical practices. For instance, it might be used to manipulate users into continuous app engagement beyond what is healthy, exploiting the discomfort associated with incomplete tasks to drive compulsive behaviors.

Bombarding users with reminders of unfinished tasks can be overwhelming and create anxiety. This can backfire, leading users to disengage entirely. Users deserve clear information and the freedom to make informed decisions. This can result in user burnout, increased anxiety, and a negative overall experience, especially if the tasks are arbitrarily extended or serve no real purpose beyond trapping the user in an engagement loop.

Preying on users with financial anxieties or those struggling with procrastination by highlighting unfinished tasks can be manipulative. Ethical design prioritizes user well-being and empowers users to make choices in their best interests.

To accommodate for these ethical pitfalls, consider adopting the following best practices:

- Promote purposeful design

Design tasks with a clear purpose and benefit to the user, rather than merely extending engagement for its own sake. Each task should add value to the user’s experience or contribute meaningfully to their goals. - Focus on long-term value

Don’t prioritize short-term conversions over long-term user satisfaction. Leverage the Zeigarnik Effect to nudge users towards completing tasks that genuinely benefit them in the long run. - Respect user autonomy

The Zeigarnik Effect should guide, not dictate, user behavior. Provide clear information and options, allowing users to make their own choices about task completion. Offer clear options to pause or stop tasks without losing progress, and avoid aggressive re-engagement tactics that exploit their desire for completion. - Balanced engagement

Strive for a balance between engaging users and allowing them downtime. Constant engagement is not the goal; rather, the aim should be to enhance user experience and satisfaction. Consider integrating features that encourage breaks and mental rest.

Real life Zeigarnik Effect examples

Fitbit

The fitness app creates daily exercise goals that leave the activity rings “open” until the user meets their target, visually and psychologically prompting completion.

Trello

The project management tool uses boards and cards to visually indicate ongoing projects. Tasks or cards not moved to the ‘Completed’ column remain visually present, urging users to resolve them.

Duolingo

The language-learning platform leaves lessons partially completed to encourage users to return. Users are visually reminded of their progress and what’s left to achieve proficiency in a language module.

Trigger Questions

- How can we visually represent unfinished tasks to keep them top-of-mind for users?

- Can we break down large tasks into smaller, achievable milestones with clear completion points?

- Are there opportunities to reward progress on unfinished tasks to motivate users towards completion?

- Does our design provide clear feedback and a sense of accomplishment when tasks are finished?

- How can we avoid overwhelming users with a constant state of incompleteness?

- Is our visual language for unfinished tasks consistent and easy to understand throughout the product?

- What strategies can we implement to remind users of their pending tasks without appearing intrusive?

Pairings

Zeigarnik Effect + Feedback Loops

Integrating the Zeigarnik Effect with feedback loops can reinforce user actions. By providing continuous feedback on incomplete tasks and showing progress dynamically, users are encouraged to achieve closure.

We remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones

We are influenced by information that provides clarity on our actions

Zeigarnik Effect + Temptation Bundling

Linking the completion of tasks (often unpleasant or requiring effort) with a pleasurable or rewarding activity can enhance the effectiveness of the Zeigarnik Effect. For instance, allowing access to a highly desirable feature or content only after certain tasks are completed can keep users engaged longer.

We remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones

Engaging in hard tasks is more likely when coupled with something tempting

Zeigarnik Effect + Scarcity Bias

E-commerce platforms often utilize Scarcity tactics by displaying limited-availability products or countdown timers on sales. This creates a sense of urgency and potential loss. The Zeigarnik Effect can complement this strategy. Imagine an e-commerce platform highlighting abandoned shopping carts with a message like “Your cart expires in 2 hours!” This combines the urgency of scarcity with the Zeigarnik Effect’s reminder of an unfinished task (unpurchased items), nudging users to complete their purchase before the limited window closes.

We remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones

We value something more when it is in short supply

Zeigarnik Effect + Commitment & Consistency

Many to-do list apps (e.g., Todoist) allow users to set recurring tasks and receive notifications. This leverages the Commitment & Consistency pattern by encouraging users to stick to their planned routines. The app can further leverage the Zeigarnik Effect by prominently displaying upcoming deadlines or incomplete recurring tasks. These visual cues, combined with reminders delivered at strategic times, create a powerful combination. The Zeigarnik Effect keeps the tasks top-of-mind, while the commitment to recurring actions and timely reminders nudge users to consistently complete their to-do list.

We remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones

We want to appear consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions

A brainstorming tool packed with tactics from psychology that will help you build lasting habits, facilitate behavioral commitment, build lasting habits, and understand the human mind. It is presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!- Uber das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen by Zeigarnik

- Principles of Gestalt psychology by Koffka

- Bluma Zeigarnik at Wikipedia (en)

- The Zeigarnik Effect: Why it is so hard to leave things incomplete. by Abhishek Chakraborty at Medium

- Zeigarnik Effect

- Zeigarnik, B. (1967). On finished and unfinished tasks. Edited by W. D. Ellis, A source book of Gestalt psychology. New York: Humanities Press. (Original work published 1927)

- Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The use of technology for self-regulation: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 770–778.

- Wegner, D. M., & Wheatley, T. (1999). Apparent mental moderators of thought suppression: The effects of thought content and self-focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1680–1691.

- Fisher, S., & Strick, M. (1973). Motivation and memory for unfinished tasks as a function of perceived difficulty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 1(1), 1–8.

- Lewin, K., Dembo, T., Festinger, L., & Sears, P.S. (1944). Level of aspiration. In J. McV. Hunt (Ed.), Personality and the behavior disorders (Vol. 1, pp. 333-378). New York: Ronald Press.

- Baddeley, A., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47-89). New York: Academic Press.

- McFarland, C., & Ross, M. (1987). The effects of attitude towards completion and interruption on recall of interrupted tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 116(2), 136-153.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Koffka, Kurt (1935). Principles of Gestalt Psychology. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. p. 334ff